Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Philippos Mandilaras, Η μάχη του Μαραθώνα [I máchī tou Marathṓna], My First History [Η Πρώτη μου Ιστορία (Ī prṓtī mou Istoría)]. Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2015, 36 pp.

ISBN

Available Onllne

Demo of 7 pages available at epbooks.gr (accessed: October 13, 2021).

Genre

Illustrated works

Target Audience

Children (Reader: 5+)

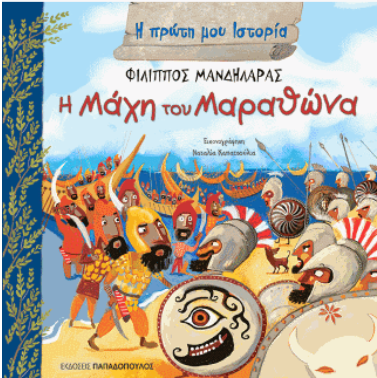

Cover

Courtesy of the Publisher. Retrieved from epbooks.gr (accessed: July 5, 2022).

Author of the Entry:

Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

Natalia Kapatsoulia (Illustrator)

Natalia Kapatsoulia studied French Literature in Athens, and she worked as a language tutor before embarking on a career as a full-time illustrator of children’s books. Kapatsoulia has authored one picture book Η Μαμά πετάει [Mom Wants to Fly], which has been translated into Spanish Mamá quiere volar. Kapatsoulia, who now lives on the island of Kefalonia, Greece, has collaborated with Filippos Mandilaras on multiple book projects.

Sources:

Official website (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Profile at the epbooks.gr (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Filippos Mandilaras

, b. 1965

(Author)

Filippos Mandilaras is a prolific and well-known writer of children’s illustrated books and of young adults’ novels. Mandilaras studied French Literature in Sorbonne, Paris. His latest novel, which was published in May 2016, is entitled Υπέροχος Κόσμος [Wonderful World], and it recounts the story of teenage life in a deprived Athenian district. With his illustrated books, Mandilaras aims to encourage parents and teachers to improvise by adding words when reading stories to children. Mandilaras is interested in the anthropology of extraordinary creatures and his forthcoming work is about Modern Greek Mythologies.

Sources:

In Greek:

Profile on EP Books' website (accessed: June 27, 2018).

i-read.i-teen.gr (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Public Blog, published 15 September 2015 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Press Publica, published 28 January 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Linkedin.com, published published 6 May 2016 (accessed: February 6, 2019).

In English:

Amazon.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

On Mandoulides' website, published 7 March 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

In German:

literaturfestival.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Translation

English: The Battle of Marathon. Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2017, 24 pp.

Summary

The textual and pictorial narrative starts with a contemporary setting: parents and children enjoy the sun and the sea in a crowded beach, ‘Marathon Beach’. As we read in red letters, this is the place where an important battle in history happened. We turn the page, and we are introduced to the Persian Empire, its geographical vastness and its great King, Darius I. By contrast, the reader comes to appreciate, Greece is much smaller. In the Greek city-states decisions were reached democratically because rulers heard what the public had to say. For Darius, however, the Greeks’ discussion of different views in the marketplace is a waste of time.

Next, we read about the Ionian Revolt. Since they were Greek, the people of Ionia turned to mainland Greece for help. Athens and Eretria, two city-states, promised to help the Ionians, and this infuriated Darius. His fleet and army were by far superior, and so Darius, together with other Persian generals, Datis and Artaphernes, decided to invade Greece. Within six days, Eretria fell. Persian soldiers anticipated that the Athenians would surrender within a month. In August 490 BCE the Persians reached Marathon. The Athenians camped near Marathon, and their military leaders, Callimachus and Miltiades, deliberated about war tactics. As the book continues, one morning, the Athenians attacked. The Persians were slow in their response. Miltiades came up with a plan to engulf the Persians from all sides. The plan was successful, and the Persians fled to the sea in a disorderly manner. The Athenians guessed correctly the Persians’ intentions to attack the city of Athens. They rushed back to their city, to the port at Phaleron. It was embarrassing for the Persians to reach Phaleron by sea and to find the Athenian army patrolling the port. So, the book states, the Persians ended their campaign, and headed back to Persia.

Analysis

The dramatic clash between the Greeks and the Persians is intense from the start of the book. Darius I is labelled in the illustration on page 3 (unnumbered page) as “King of the Universe”. The Persian Empire, with its major cities (Sardis, Babylon, Susa, and Persepolis) nicely marked on the map, seems to be endless, like the universe. The word ‘universe’, in particular, could resonate with modern science fiction, and with films such as Star Wars, and this may again intensify readers’ expectations for suspense in the story.

Darius seems to misunderstand the functioning of democracy. Natalia Kapatsoulia, the illustrator, shows cleverly the Greeks talking “blah blah blah”. Two points may emerge here. First, the Persian King may not understand the Greek language. If so, the illustration reverses the ancient Greeks’ traditional construction of barbarians as people who were not competent in the Greek language but, instead, uttered incomprehensible and repetitive sounds. Second, the illustration could highlight a trade-off between efficiency and democracy. It takes time for an assembly of people to reach consensus, and, indeed, Darius apparently may dislike a delay in decision-making, and not necessarily democracy as a political system. Thus, the Greek and Persian mentalities are not presented as worlds apart, and as a clash between Greeks and Barbarians. Rather, text and image seem to convey that there are misunderstandings between the two sides.

There is nothing in this book, therefore, about a competition between two distinct cultures (or civilizations). The Greek army’s victory results from good strategic thinking at the battlefield, and not from the Greeks’ cultural superiority. The balanced representation of the Persians may appeal to young children who grow up in multi-ethnic environments.

The Greeks and Persians are shown differently by Kapatsoulia, and this helps readers to identify quickly who is who in the illustrations. The Greeks wear helmets with large crests, while the Persians have pointed hats. Such stereotypical depictions are common in popular culture, such as in Rudolph Maté’s movie The 300 Spartans (1962). In Classical art, a pointed hat signifies generic non-Greeks, and is not an exclusive Persian stylistic feature. In a late sixth-century black-figured pinax (plate) by the painter Psiax in the British Museum the hat is worn by a Skythian archer.*

It is commendable that the illustrations take cues from ancient art. The cues may help in children’s familiarisation with material culture that is shown in school text books about ancient history. The illustration of the Ionian Revolt may also play on the theme of familiarity. Men and, remarkably, women, mostly of a young age, are shown protesting against high taxes. With raised hands and mouths wide open they demand more democracy and freedom. Demonstrations are common in Greece, and other western countries that have been undergoing socio-economic reforms in recent years. Seemingly, in learning about ancient history, young and adult leaders are reminded of modern realities. As a result, this book is not only about a major historical event from 490 BCE. Rather, the content seems to make oblique references to modern agendas, such as intercultural communication, strategic thinking, and human-rights activism.

*British Museum, 1867,0508.941. See here (accessed: January 22, 2019)

Further Reading

Information about the book:

Addenda

The entry is based on the English edition.