Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

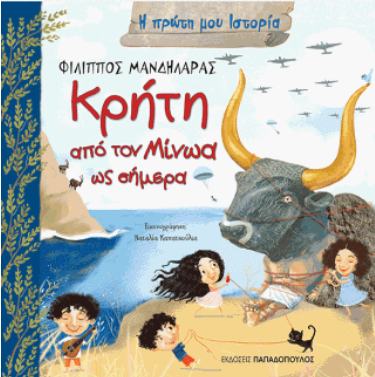

Filippos Mandilaras, Κρήτη – Από τον Μίνωα ως σήμερα [Krī́tī – Apó ton Mínōa ōs sī́mera], My First History [Η Πρώτη μου Ιστορία (Ī prṓtī mou Istoría)]. Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2016, 36 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Illustrated works

Target Audience

Children (5+)

Cover

Courtesy of the Publisher. Retrieved from epbooks.gr (accessed: July 5, 2022).

Author of the Entry:

Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

Natalia Kapatsoulia (Illustrator)

Natalia Kapatsoulia studied French Literature in Athens, and she worked as a language tutor before embarking on a career as a full-time illustrator of children’s books. Kapatsoulia has authored one picture book Η Μαμά πετάει [Mom Wants to Fly], which has been translated into Spanish Mamá quiere volar. Kapatsoulia, who now lives on the island of Kefalonia, Greece, has collaborated with Filippos Mandilaras on multiple book projects.

Sources:

Official website (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Profile at the epbooks.gr (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Filippos Mandilaras

, b. 1965

(Author)

Filippos Mandilaras is a prolific and well-known writer of children’s illustrated books and of young adults’ novels. Mandilaras studied French Literature in Sorbonne, Paris. His latest novel, which was published in May 2016, is entitled Υπέροχος Κόσμος [Wonderful World], and it recounts the story of teenage life in a deprived Athenian district. With his illustrated books, Mandilaras aims to encourage parents and teachers to improvise by adding words when reading stories to children. Mandilaras is interested in the anthropology of extraordinary creatures and his forthcoming work is about Modern Greek Mythologies.

Sources:

In Greek:

Profile on EP Books' website (accessed: June 27, 2018).

i-read.i-teen.gr (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Public Blog, published 15 September 2015 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Press Publica, published 28 January 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Linkedin.com, published published 6 May 2016 (accessed: February 6, 2019).

In English:

Amazon.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

On Mandoulides' website, published 7 March 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

In German:

literaturfestival.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Summary

The narrative starts by making a point of Crete’s unique geographical location. The island resembles a bridge between Europe, Asia, and Africa. The book explains that Crete has seen lots of activity ever since its first inhabitants arrived eight thousand years ago. Crete has been far from a quiet place also because of its mythological connections. We are told that Zeus grew up here and brought Europa to the island. The giant Talos protected Crete end to end. Later, King Minos built the labyrinth for the Minotaur, whom he fed with Athenian youths until Theseus fought the beast. Then, mythology gave its way to history. The Minoans, who mastered the seas, came and built palaces. At some point, the palaces were obliterated from view, but Sir Arthur Evans excavated and rediscovered them. Time passed, and different peoples conquered Crete, the Saracens, the Byzantines, the Franks, and the Venetians. The Letters and the Arts flourished on the island in the period from the 15th to the 17th centuries, before the Ottomans captured Crete. The 19th and early 20th centuries saw the Greeks’ struggle for liberation and unification with mainland Greece, which happened in 1913. The people of Crete fought bravely also in World War II. The book closes with verses from the 17th-century poem ‘Erotokritos’.

Analysis

Mandilaras offers a concise and informative historical overview of Crete that includes a consideration of mythology, prehistory, archaeology, and the arts (painting and poetry). The diachronic narrative, especially with its emphasis on groups of peoples that came and went, may recall that of another book in the same series about the city of Thessaloniki.* Decastro’s book about Crete, ‘Let’s go to Crete’, from the series ‘Short City Guides’, by contrast, seems to pay more attention to sights, folklore, and modern cuisine, presumably because it addresses principally an audience of foreign visitors.

The book here targets Greek children and it aims to equip them with knowledge that will be useful in their schooling.

Myth looms large, especially in the early part of the book. The teaching of ancient history in Greek elementary school starts with the teaching of mythology in the third grade of the Greek system (Γ’ Δημοτικού). For this grade, the history schoolbook’s subtitle reads ‘from mythology to history’ (my translation), signaling the assumed strong ties between the two.** There have been recent suggestions in Greece for changing school curricula and aligning the teaching of mythology with social anthropology.*** In fact, Mandilaras and Kapatsoulia appear to enrich references to ancient myths with cultural elements, ancient and modern. In doing so, they may bring mythology closer to anthropology. I will discuss two cases below.

Firstly, in the opening page we read that Crete is the birthplace of gods and heroes, and we see people in summer clothes at a beach. Curiously, a sunbather’s head is covered by a horned bull’s head, which is a recognizable artefact of Minoan civilization from ca. 1500 BCE.**** This archaeological find from Knossos is a finely crafted libation vase representing a sacred animal in Minoan religion. The bull’s head, more poignantly perhaps, has become an iconic image of ancient Crete and is commonly depicted in textbooks about the island, as well as in souvenirs and postcards. Whether the sunbather is real or imaginary remains unresolved. He could be a tourist who is fascinated by ancient material. The bull’s head is featured also in the book’s cover, where it denotes, in all likelihood, the Minotaur. In effect, in Kapatsoulia’s illustrations the myth of the Minotaur is conflated with ancient evidence and their modern reception.

Secondly, Crete has been a turbulent place throughout the ages, as it emerges from the book as a whole. Mandilaras states explicitly that its troubles started with the gods, since Rhea hid Zeus in Crete when she decided not to feed Cronus with his children. Minos, one of Zeus’ children with Europa, built the labyrinth to confine the fearsome monster Minotaur, who was a man-eater like Cronus. The illustration shows visitors inside the palace of Knossos with its characteristic red interiors and frescoes. A young boy is startled as he gazes at a fugitive ghost-like image of the Minotaur on a wall. Such an image is unknown archaeologically. Kapatsoulia conveys that the spirit of the Minotaur lives on and it has an impact on modern viewers. Myth, with its unbelievable monstrosity, is associated with real spaces and experiences, with the palace and the boy’s reaction respectively. Imaginary creatures can be seen and felt when visiting an archaeological site. The immediacy of ancient culture (the palace and its décor in this instance) adds credibility to stories about monsters and cannibalism. Readers may develop an anthropological interest in these stories, prompted also by the psychological effect of awe-inspiring creatures.

With Theseus’ victory over the Minotaur, the salience of mythology comes to an end. History starts with the arrival of the Minoans from Asia Minor. This clear divide between myth and history could be suited to young children’s learning. Further simplifications follow. A label indicates that the Minoan civilization is very old, running from 3000 to 1420 BCE. Yet, no mention is made to prehistory, as ‘prehistory’ might have been a confusing term for children. The Minoans’ dominance of the seas is presented as a fact, whereas in academia a Minoan thalassocracy is disputed and often considered as a fallacy.*****

The existence of the Minoans, nonetheless, is uncontested. We turn the page and we encounter Arthur Evans’ excavations of the palace of Knossos. We read that this man, whose name, and the title he received after he was knighted in 1911, is given in full (Sir Arthur John Evans), is responsible for recovering the lost palace of Knossos and the civilization that was called ‘Minoan’. Here, Mandilaras might allude to the Minoan civilization being a construct, as appreciated in academia.****** In the illustration, locals, including children, interact with the British archaeologist, asking him questions about the collapse of the palace and about the island’s inhabitants in subsequent eras. Arthur Evans is erudite and has answers to all questions, including to those about Crete’s Byzantine heritage. Archaeology, therefore, can illuminate aspects of history, and is of interest to the people of Crete. Text and illustration here point to the importance of public engagement. There might be, however, subtle undertones for colonial relations between a learned foreigner and naive locals who thirst for knowledge.

The following pages in the book make reference neither to myth nor to archaeology, as they cover periods from Late Antiquity to the present. Children will revisit these historical events much later in their schooling, mostly at High School (Gymnasium and Lyceum, ages 13 to 18). Nevertheless, the theme of the island’s interactions with the outside world comes to the fore once again, and this may be of interest to young children. The island changes hands many times, and changes its name to Candia under the Venetians. Domenikos Theotokopoulos, a fine painter from the period of the Cretan Renaissance (15th to 17th century CE), became known ‘in the entire world’ (σ’ όλο τον κόσμο) as El Greco. Children may like, moreover, the verses at the book’s closure, as these could resonate with folktales. The verses are by romantic poet Vitsentzos Kornaros, also of the Cretan Renaissance.******* In translation the verses read:********

The Cycles with their trails that rise and fall;

Time’s Wheel that knows the height and depth of All,

That bears Fate’s whims and turns not back again,

But whirls with Good and Evil in its train.

* https://www.epbooks.gr/product/101733/θεσσαλονικη-πολη-στο-σταυροδρομι-δυο-κοσμων (accessed January 30, 2019)

** http://www.pi-schools.gr/books/dimotiko/history_c/IST_C_DHM_BK.PDF (accessed January 30, 2019).

*** https://www.tanea.gr/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Γ-Δημοτικού.pdf (accessed January 30, 2019).

**** http://odysseus.culture.gr/h/4/eh430.jsp?obj_id=7883 (accessed January 30, 2019).

***** See, for example, Anthony Harding, “Interactions and -isations in the Aegean and beyond”, Antiquity 91 (2017): 250–253 (accessed February 11, 2019).

****** Ilse Schoep, "Building the Labyrinth: Arthur Evans and the Construction of Minoan Civilization", American Journal of Archaeology 122.1 (2018): 5–32. DOI: 10.3764/aja.122.1.0005 (accessed February 11, 2019).

******* See http://www.snhell.gr/references/quotes/writer.asp?id=167, (accessed January 30, 2019).

******** For the translation see (accessed January 30, 2019).

Further Reading

Information about the book: www.epbooks.gr (accessed February 11, 2019)

Addenda

Published in Greek, 15 March 2016. Hardbound.