Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

James Reeves. Heroes and Monsters: Legends of Ancient Greece. Glasgow: Blackie and Son Ltd., 1969, 224 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Adaptations

Fiction

Myths

Target Audience

Children (age 8–10)

Cover

We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover.

Author of the Entry:

Robin Diver, University of Birmingham, robin.diver@hotmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

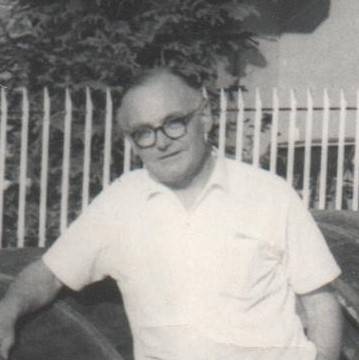

Picture of James Reeves, uploaded by Emilypiazza. Retrieved from Wikipedia, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 (accessed: January 5, 2022).

James Reeves

, 1909 - 1978

(Author)

James Morris Reeves was a British poet, teacher, author and editor. He studied English at Jesus College, Cambridge, where he co-founded Experiment, a literary magazine. He then became a teacher, but had to retire in 1952 due to issues with eyesight. After retirement, he dedicated himself full-time to writing and editing.

He published his first book of poetry, The Natural Need, in 1936 with Robert Graves’ publisher, The Seizin Press, and his early poetry is alleged to resemble that of Graves. He also wrote poetry for children. His anthology books included English Fables and Fairy Stories (1954), also published as Fairy Tales from England; Stories from England (1954, possibly the same book again under a different name); The Holy Bible in Brief (1970) and The Secret Shoemakers and Other Tales (1966). He also produced two additional Greek myth books, The Trojan Horse (1968) and The Voyage of Odysseus (1973).

Sources:

Faber and Faber (accessed: July 29, 2019).

Biblio (accessed: July 29, 2019).

Wikipedia ( accessed: July 29, 2019).

Bio prepared by Robin Diver, University of Birmingham, RSD253@student.bham.ac.uk

Sara Silcock (Illustrator)

Sara Silcock is a children’s book illustrator known chiefly for her work on Enid Blyton books (e.g. illustrations to The Very Peculiar Cow and Other Stories; book cover for one edition of Amelia Jane Again! (1946, accessed: July 29, 2019). Many of the books credited to her name, both those of Blyton and other authors, seem to be anthology books; for example The Lonely Mermaid and Other Stories by Derek Hall (1999). In terms of classical content, her illustrations also appear on a book of Aesop’s Fables (1979, see here, accessed: July 29, 2019).

Sources:

Profile at goodreads.com (accessed: July 29, 2019).

Profile at The Enid Blyton Society (accessed: July 29, 2019).

Bio prepared by Robin Diver, University of Birmingham, RSD253@student.bham.ac.uk

Summary

This is an anthology book for children which presents the key figures and stories from classical mythology. The chapters are lightly illustrated, with one or two line drawings per chapter.

- Introduction.

- Pronunciation Guide (and map of Ancient Greece).

- The Beginning of Man: Prometheus and Pandora.

- Winter and Summer: Demeter and Persephone.

- Daedalus and Icarus.

- Phaeton’s Journey.

- King Midas (divided into ‘The Golden Touch’ and ‘A Pair of Ass’s Ears’).

- Jason and the Argonauts (divided into ‘The Boyhood of Jason’, ‘Voyage of the Argo’ and ‘The Golden Fleece’).

- The Labours of Heracles.

- Apollo and Daphne.

- The Gorgon’s Head (divided into ‘Perseus and Danae’, ‘The Slaying of Medusa’, ‘The Giant Atlas’, ‘Perseus and Andromeda’ and ‘The Return of Perseus’).

- Philemon and Baucis.

- Eros and Psyche.

- Ceyx and Alcyone.

- Orpheus and Eurydice.

- Theseus and the Minotaur (divided into ‘The Journey to Athens’ and ‘The Minotaur’).

- Arion.

- The Fall of Troy.

- Odysseus and Polyphemus.

- Odysseus and Circe.

- Scylla and Charybdis.

- The Homecoming of Odysseus.

Analysis

These retellings are adapted extremely closely from Ovid, to the point they are at times a loose English translation.

The introduction claims that the myths retold here are "some of the world’s greatest folktales" (p. 7) and explains that folktales are stories from ‘the common people of any land’ with ‘no known original author’. Given Reeves also wrote anthologies of fairy tale and western European folklore, this is not surprising. Curiously, however, the title, Legends of Ancient Greece, frames the stories as legend rather than myth, as if there might be a semi-historical basis to the stories. (Given the focus of this book is monster slaying tales, we can probably safely assume there is not.)

Reeves also uses the introduction to posit a view of Western culture as existing thanks to Greece – the Greeks, he claims, "had the virtue of curiosity" (p. 7). ‘Had it not been for the enquiring mind of Greece, western Europe would have known little progress’. This miraculous curiosity of the Greeks is proved by the existence of Greek mythology to explain the origins of the world, showing the Greeks wondered about where they had come from. Obviously, this ignores the near universal existence of creation myths in other ancient religions.

In his retellings, Reeves overall changes little from his (mainly) Ovidian source material. He rejects a lot of commonplace literary innovations in other children’s anthologies of myth. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s addition of a daughter for King Midas, which has become almost universal in children’s myth anthologies since then (see Deborah Roberts, The Metamorphosis of Ovid in Retellings of Myth for Children 2015) is not included in Reeves, for example. He also feels the need to hint at the unhappy ending to the Jason and Medea story, although he does not actually give it. In the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, it was common for children’s anthology books to only lightly rework ancient sources (see Edith Hamilton’s 1942 Mythology, Olivia Coolidge’s 1949 Greek Myths and in particular, Rex Warner’s 1950 Men and Gods: Myths and Legends of the Ancient Greeks. By the 60s, however, more innovative children’s anthologies were becoming popular again, making Reeves’ approach somewhat old fashioned for the time – see the D’Aulaires D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths 1962; Robert Graves’ 1960 Greek Gods and Heroes and Bernard Evslin’s 1967 Heroes, Gods and Monsters of the Greek Myths.) In the case of Reeves, his clear reliance on Ovid’s text over other versions clashes with his initial claim to be retelling oral folklore with no written source.

Like many other authors of children’s anthologies of myth, Reeves uses the Prometheus and Pandora stories to philosophise on the relationship of humanity to animals and men to women. (For other anthologies that do this, see in particular Bob Blaisdell’s 1996 Favorite Greek Myths.) Humans (or ‘man’) Reeves claims, are different from the animals because we like to look at the sky and this leads to our curious nature. Classical myth is thus linked to twentieth century ideas of human bipedalism as a major cause of human divergence.

Women are created because "Zeus determined that man needed a companion and a helpmate" (p. 19), echoing popular Christian phrasing when describing women’s role. However, ‘some believed that woman was sent, not as a friend to man, but to plague him for having taken the gift of fire’ (p.19). Since Hope is included in Pandora’s box, Hope is called "woman’s gift to man" (p. 20). Clearly, there is a deeper metaphor intended about the alleged emotionally uplifting role of women in the male life course.

Some of the relatively small number of changes Reeves makes from ancient material do in fact follow the latter view on gender roles. For example, in Reeves, Persephone goes with Hades mostly willingly because she pities his loneliness – "her heart was moved to pity by the sight of the stern and lonely god" (p. 23). Whilst this might be reflective of 1960s ideas of womanhood, it also looks ahead to the ‘sympathetic Hades’ trend that would become popular in anthologies of the 1990s onwards, where Hades is a lonely ‘nice guy’ deserving of pity (see e.g. Geraldine McCaughrean, Orchard Book of Greek Myths 1992; Heather Alexander A Child’s Introduction to Greek Mythology 2011).

There is something of a disconnect with Perseus’ character between what the narration and other characters assert about him, which fits the noble and brave hero character common to children’s anthologies, and what Perseus shows us about himself through dialogue. In his conversations with Atlas and Andromeda’s parents, Perseus is arrogant and aggressively asserts his connection with the gods as a measure of worth without demonstrating any other positive traits. However, the narrative voice and other characters never seem aware of this. For example, when Perseus decides to take Andromeda back to his homeland, "With her heart full of happiness the beautiful Andromeda prepared to go with her brave and noble husband." (p. 115). This disconnect may be due to Reeves transcribing Ovid’s text uncritically whilst also trying to insert descriptions of the blandly good hero typical of mid-twentieth century children’s stories. Perseus in Reeves comes across as a ‘hero’ who essentially achieves very little, since his victory is handed to him by his divine siblings Athene and Hermes when they decide to aid him by giving him weapons that make it easy for him to kill Medusa, and he achieves everything else even more easily since he has her head. The nepotism that has fuelled the career of this hero is made even more obvious when Perseus will not stop boasting about his divine family and how his relation to gods makes him a hero and person of note to anyone who will listen. In Ovid, all of this is probably intentional, but Reeves’ authorial voice lacks Ovid’s self-awareness.

There is also perhaps a sense of ‘young boys need fathers’ to Reeves’ Perseus retelling. When Perseus is made aware of his divine paternity by Athene and Hermes this seems to give him a boost of confidence to the point it actively reshapes his identity. When he returns to Seriphos at the end, the nobles observe that "he was a handsome youth, taller and stronger than ever before" (p. 117). This sense of the importance of knowing one’s patrilineal ancestry is enhanced by the fact that this otherwise vicious incarnation of Perseus seems to have no anger against Acrisius, the grandfather who abused and attempted to murder him and his mother. He sets out to reunite with Acrisius at the end and "hoped that his grandfather would by this time have forgiven them." (p. 118). Why Perseus and Danae should require Acrisius’ forgiveness, and not the other way around, is unclear.

One element of Ovid’s Perseus story that Reeves does alter is the backstory of Medusa. Instead of being raped by Poseidon in Athene’s temple and transformed into a gorgon as punishment, Medusa here boasted that she was more beautiful than Athene. This gives her story a curious link to that of Andromeda, but whilst Andromeda and her mother are presented as deserving of rescuing from their fates, Medusa is apparently not.

Addenda

Target Group: 8–10 years of age according to this Amazon review (accessed: August 16, 2019).