Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Carlo Collodi, Le avventure di Pinocchio. Storia di un burattino, illustrazioni di Enrico Mazzanti. Firenze: Libreria Editrice Felice Paggi, 1883, 236 pp.

Available Onllne

Google books: original first edition (accessed: May 7, 2020).

Genre

Bildungsromans (Coming-of-age fiction)

Didactic fiction

Fantasy fiction

Novels

Target Audience

Children (also crossover )

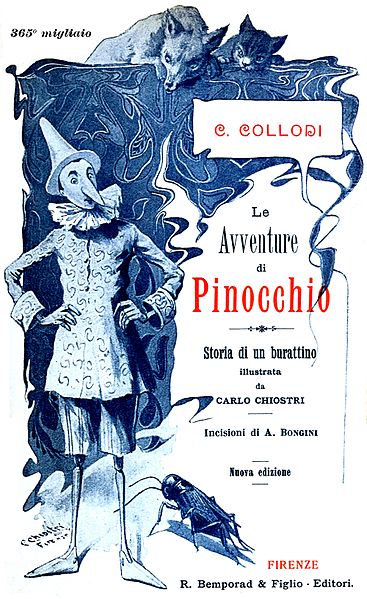

Cover

Cover by Carlo Chiostri. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons, public domain (accessed: June 26, 2020).

Author of the Entry:

Beatrice Palmieri, University of Bologna, beatrice.palmieri@studio.unibo.it

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Daniel A. Nkemleke, University of Yaoundé 1, nkemlekedan@yahoo.com

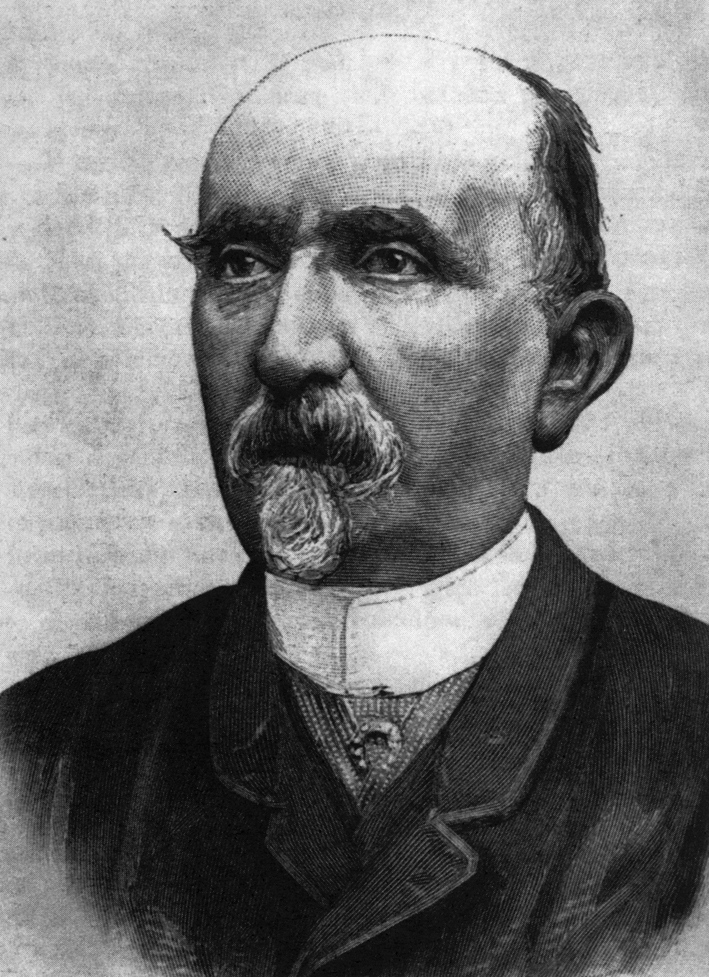

Portrait of Carlo Collodi, available at commons.wikimedia.org, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike (accessed: June 26, 2020).

Carlo Lorenzini

[Carlo Collodi] , 1826 - 1890

(Author)

Carlo Lorenzini (pseudonym: Carlo Collodi) was born in Florence, but spent his childhood in a small town called Collodi, name which inspired his pseudonym. He was a fervent literatus and from the beginning of his career he collaborated with the most prestigious Florentine bookshops and newspapers. Animated by Mazzinian ideals, he took part in the two wars of independence, in 1848 and in 1859, and founded one of the major humoristic-political newspapers of the time: Il Lampione. In 1875 he was commissioned to translate the most famous French fairy tales, including those of Perrault, d’Aulnoy, de Beaumont. From that moment on, he devoted himself to the production of works for children, and thanks to the success achieved with the publication of Pinocchio, he became the editor of the Giornale per i bambini, one of the earliest Italian weekly magazines for children, in 1893.

Sources:

treccani.it (accessed: May 7, 2020);

treccani.it( accessed: May 7, 2020);

it.wikipedia.org (accessed: May 7, 2020).

Bio prepared by Beatrice Palmieri, University of Bologna, beatrice.palmieri@studio.unibo.it

Enrico Mazzanti

, 1850 - 1910

(Illustrator)

Enrico Mazzanti was a Florentine engineer. He began his career dedicating himself to the creation of iconographic apparatuses for scientific and literary publishing, then he specialized in illustration for children. In addition to Collodi, he collaborated with many children's writers, including Emma Perodi, for whom he illustrated cartoons in the Giornale per i bambini. He illustrated children’s books for some of the main Italian publishing houses and was also appreciated abroad: his Pinocchio’s cartoons were requested by readers in USA, Spain and France.

Sources:

it.wikipedia.org (accessed: May 7, 2020).

Bio prepared by Beatrice Palmieri, University of Bologna, beatrice.palmieri@studio.unibo.it

Adaptations

The story has been adapted into many genres on stage and screen, some keeping close to the original Collodi narrative while others treating the story more freely. There are at least fourteen English-language films based on the story, not to mention the Italian, French, Russian, German, Japanese and many other versions for the big screen and for television, and several musical adaptations.

Based on wikipedia.org (accessed: May 7, 2020).

Translation

According to the extensive research done by the Fondazione Nazionale Carlo Collodi in the late 1990s and based on UNESCO sources, the book has been adapted in over 260 languages worldwide, while as of 2018, it has been translated into over 300 languages. That makes it the most translated non-religious book in the world and one of the best-selling books ever published, with over 80 million copies sold in recent years (the total sales since its first publication are unknown because of the many public domain re-releases begun in 1940). According to Francelia Butler, it remains "the most translated Italian book and, after the Bible, the most widely read". (Based on wikipedia.org, accessed: May 7, 2020).

Summary

The Adventures of Pinocchio. Story of a Puppet narrates the quest of a wooden animated marionette, Pinocchio. It all starts with the best known incipit of all time: “Once upon a time, there was… “A king!” my little readers will say right away. No children, you are wrong. Once upon a time there was a piece of wood.” *

And so, we are at once catapulted into the shop of a carpenter, Master Antonio, called Master Cherry because the tip of his nose was always red. He was in the process of carving a block of wood into a leg for his table, when he suddenly heard that log talking, begging him not to strike so hard. Terrified of this extraordinary event, he did not hesitate to get rid of the talking piece of wood by giving it to Geppetto, who had just arrived at that moment. Coincidentally, Geppetto was just looking for a piece of wood to carve into a puppet, planning to make a living as a puppeteer, so he accepted without hesitation: it was a business for both. As soon as he got home, he immediately got to work to carve his puppet until he created a wooden child: he decided to call him Pinocchio and he would have been his son.

As soon as he begins to take shape, and then once finished, Pinocchio behaves like a naughty and mischievous child: the first thing he does, after kicking his father, is to run away and cause poor Geppetto to be temporarily arrested. The inclination to disobey and get into trouble is immediately evident; nevertheless Geppetto treats him as the most precious asset he has, and in order to ensure his education like all the other children, he sells his only coat to buy him a booklet.

From there on, the plot will be dotted with adventures and misadventures with which the protagonist will struggle due to his inexperience of the world. On his way to school, Pinocchio runs into the Great Marionette Theatre and not only does he immediately forgets the promise made to his father to attend school, but he also wastes his father’s sacrifice by reselling the book to buy tickets for the show. This choice, dictated by the selfish will to satisfy his pleasure and curiosity, takes him into the clutches of Mangiafuoco. The puppet master takes pity on him and decides to release him: he also decides to give him five gold pieces with which to return to his father. On the way home, he is approached by a couple of scammers, the Cat and the Fox: the two convince the boy to plant his coins in the Field of Miracles, outside the city of Catchfools, in order to make them grow into trees of golden coins. Pinocchio lets himself be duped and follows them, unaware of the fact that they want to rob him, indeed they devise a deception: they make the boy go alone, at night, towards the Field of Miracles, and disguised as assassins, they ambush him. Once again Pinocchio gets in trouble, for not having listened to the talking cricket: the two criminals catch and hang him.

This time the puppet is saved by the intervention of the Blue Fairy to whom, however, he told what had happened filling the stories with lies: Pinocchio sees his nose stretch out of all proportion and grow until it is so long that he cannot turn around in the room. Despite this, the Fairy is kind and proposes to Pinocchio to live with her in the cottage together with his father. Unfortunately, whenever he has the chance to redeem himself, Pinocchio sabotages it. As a matter of fact, he once again falls into the trap of the Cat and the Fox: this will lead the puppet to lose his money once and for all, to risk being arrested for being robbed, to become a watchdog as punishment for having stolen from a farmer some bunches of grapes, and finally to return to the Fairy’s cottage to find her gone. While Pinocchio is crying desperately, a pigeon warns him that Geppetto is about to embark on the new world in search for Pinocchio and offers to take him to the beach. Seeing that his father has set sail, Pinocchio throws himself into the sea, until the waves bring him to the Island of Busy Bees. Here he finds the Fairy, now grown up, who forgives him and promises to take care of him and to be his mother only on condition that Pinocchio is committed to becoming an educated and good boy at school at least for a year.

For the umpteenth time Pinocchio, despite starting with the best of intentions, disappoints the Fairy: he skips the school at the invitation of some envious companions with whom he ends up having a fight, he is chased by the police, risks being fried in a pan by a fisherman in a cave; from which he is saved by a dog. Returned to the Fairy, he promises to follow now the right path to become a real child. For a whole year he goes to school and behaves well, but the day before the much-needed transformation, he is persuaded by Candlewick, his schoolmate, to go to the Toyland, a place where children are required only to have fun and not to work. After extravagant five months, Pinocchio turns into a donkey, along with all the boys who have decided to live in that place. Sold first to a circus impresario, he is obliged to perform, and during a show he notices the Fairy watching him in the audience. Then the donkey is sold to a buyer who would like to use the skin for a membrane of a drum and he throws Pinocchio into the water with the intention of drowning him. Freed of his donkey shell thanks to a fish sent by the Fairy, he is a puppet again and runs away swimming.

In the sea, however, he is swallowed by a fish-dog – the same one that two years earlier had also eaten Geppetto - despite the advice of the Fairy, this time in the form of a little blue-furred goat who watches him from atop a high rock. Father and son thus find themselves inside the animal's belly, from which they finally manage to escape. Pinocchio, after all these adventures, learned his lesson and decides to take care of his poor father, old and sick, by working hard and making a living. For the good conduct shown towards Geppetto, the Fairy forgives all the harm that the puppet had caused and turns Pinocchio into a real child. Looking at his former puppet body that lies lifeless on a chair, Pinocchio says: “How funny I was when I was a puppet! And how happy I am now to have become a good boy!”

* Carlo Collodi, The adventures of Pinocchio. Story of a puppet, translated by Nicolas J. Perella, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005, 83 pp.

Analysis

In more than a century, Pinocchio has touched and fascinated millions of children and adults around the world. The first eight episodes were published in 1881, as a serialized novel in the Giornale per i bambini. The success of this story was so high among children that the author was forced to carry on the story: it took him two years to reach the end, that is, the 1883 edition consisting of 36 episodes, which we all know now. A surely unexpected and not sought-after success, given that the author initially defined this work as a “childishness”. However, the impact this novel has had on world’s culture has been so considerable that we might call it modern mythology. The ability to penetrate so deeply into culture is perhaps due to the fact that myth is probably inherent in the plot. In fact, among various interpretations that this story has generated, one cannot miss the claim that classical culture was the primary source of inspiration for the work.

In Greek, the word for wood is hylê, the raw material from which everything is made, which is worked and modelled by a demiurge. Originally, in ancient Greece, the term “demiurge” was the ordinary word for “craftsman” or “artisan” and Plato adopted it in his dialogue Timaeus to describe the creator deity who takes the pre-existing material of chaos, shapes it and gives it life by providing it with a soul. Geppetto’s character can perhaps be compared to this figure, certainly in an ironic way: the first three chapters of the novel are dedicated to the creation of Pinocchio starting from a piece of wood, but since the log was already animated, and since not a real human was fashioned from it but a puppet, then Geppetto proves to be a weak and, in a certain sense, ridiculous demiurge. Indeed, his creature is the parody of the perfect one which is supposed to be born thanks to the intervention of the demiurge. According to Plato’s narrative, the demiurge is unreservedly benevolent and hence desirous of a world as good as possible, but here, Pinocchio represents the opposite of this desire: he is mischievous and disobedient and he detaches from the ideals of perfection and order which inspired the demiurge – he is a puppet that appears to be doomed. Here the myth of the demiurge intertwines with the image of the puppet that Plato introduces in his latest work, The Laws, in order to explain that the divinity programmed this complex machine so that it could be guided towards acquiring a virtuous disposition. Plato imagines that this prodigious toy is moved by ropes that jerk violently towards shameful and nefarious actions, such as dissolute pleasures and irrational fears, and this is exactly what Pinocchio does in the first part of the novel: until he is hanged, we see the pranks of a daredevil Pinocchio, who runs through the streets and fields in the image of a wild, rebellious and anarchist nature of childhood, not yet tamed and civilized by adults. However, Plato recognizes also the “golden rope” of reason, that the puppeteer-demiurge should pull towards virtue observing precise laws, but in the novel, Geppetto, the weak demiurge, does not fulfil this task. Or rather, he tries, recognizing the important role of education and attempting to ensure the puppet’s schooling. Indeed, even Plato recognizes education as the decisive way of directing the pleasures and pains of children towards virtue, separating their instinct from vice. But this goal Pinocchio will achieve very late, without the help of any puppeteer who pulls his strings: Pinocchio develops his conscience at his own expense, adventure after adventure, driven by his instinct like a naïve child who pursues fun and pleasures.

This journey towards maturity is told by the author according to a picaresque narrative that recalls The True Story of Lucian of Samosata in its fantastic and imaginary journey, and Metamorphoses by Apuleius, in the continuous change of forms with which the novel is imbued. In the second half of the novel, after the hanging, Pinocchio juggles between wandering, escapes and freedom, changes of status. All these moments follow the pattern of a crossroads where Pinocchio is called to make a choice. Each of these choices marks a stage of his initiation journey towards maturity, which he will reach only after learning to follow the path of sinceritas. In a universe defined by Manichean dualism in which good corresponds to school and work, and evil to prison and hospitalization, our hyperkinetic puppet always seems one step away from redemption, but as soon as he approaches it, something intervenes to make him deviate from the right path. Pinocchio wants to be sincere; he distinguishes between right and wrong, but in the end, he is a child and behaves as such, growing up and learning from his mistakes.

In reality, this educational path takes place in constant evolution, where the key word is the verb “to become”: not only the characters that Pinocchio meets take on different shapes from time to time (the Fairy child and then adult, the living cricket and then his shadow, Candlewick child and then donkey), but above all the protagonist is subject to continuous metamorphosis. Manganelli defines him as an “escape animal”. These transformations are not only physical changes: for example, we see Pinocchio’s nose getting longer, his feet burning, not to mention the complete metamorphosis into a donkey – an Apulian memory. In addition to this, the theme of transformation develops through the characters taking on different roles, e.g., when Pinocchio takes Melampo dog’s place. Finally, transformation means also appearing to others as somebody else. Think for example, when the green fisherman sees Pinocchio as a fish, or when puppets at the theater see him as their brother. All these steps are metaphors for the construction of the protagonist’s identity, which can be said to have been first completed symbolically, after he and his father manage to escape from the fish-dog’s stomach. This image recalls The True Story by Lucian of Samosata, the text with which Pinocchio can be associated based on the amount of fantastic encounters and adventures reaching the limit of the improbable. One of these is the whale episode: Lucian said that during his journey beyond the Pillars of Hercules he ended up in the belly of a whale where he met an old man and a boy who lived there with other people. Like Geppetto and Pinocchio, Lucian and his companions managed to escape by coming out of the whale’s mouth, which from a symbol of captivity became a symbol of freedom. Furthermore, Pinocchio’s identity is physically complete with the last and most awaited metamorphosis: when the puppet becomes a real child.

Collodi adapts the timeless fantasies of the fairy tale and the reminiscences of classical culture to the contemporary Italian society, sliding from the fairy tale towards the realism of the novel. In fact, we find ourselves in a universe recalling Aesop's fairy tales, among talking animals: the Cat and the Fox, the talking cricket, to quote the best known, but within the novel men and animals coexist and interact without alienating effects. The Blue Fairy, like Isis for Apuleius, mediates between the animal and human world. However, within this fabulous context, Collodi is the first to introduce the world of childhood into Italian literature in a realistic and non-stereotyped way: Collodi breaks the topos of the puer senex – mature, diligent and studious from the first moment of his appearance. The author allows Pinocchio to be a real child guided by the threads of innocence, curiosity, desire to play and have fun. The thread of reason and conscience must be gained by himself, learning to discover the world by trial and error. In this way, with the help of ancient culture, Collodi revolutionized the world of children’s literature and education in Italy in the 19th century.

Further Reading

Rodari, Gianni and Verdini, Raul, La filastrocca di Pinocchio, Editori riuniti, 1974.

Manganelli, Giorgio, Pinocchio: un libro parallelo, Torino: Einaudi 1977; Milano: Adelphi 2002.

Addenda

The entry is based on the edition: Carlo Collodi, Le avventure di Pinocchio, Varese: Libraria editrice S. r. l., 2017, 160 pp.