Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

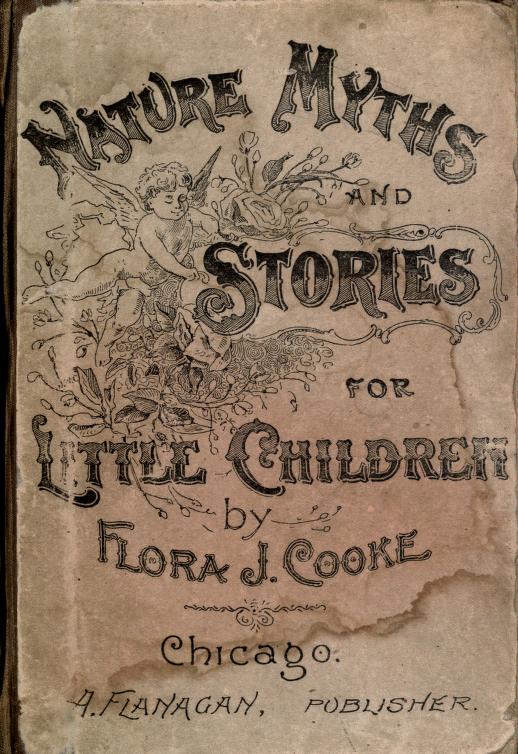

Flora J. Cooke, Nature Myths and Stories for Little Children. Chicago: A. Flanagan Publisher, 1895.

All references here are to Flora J. Cooke, Nature Myths and Stories for Little Children. The Teacher’s Helper; Vol. 1, No. 1, August, 1894. No location: Leopold Classic Library.

ISBN

Available Onllne

loyalbooks.com (accessed: July 31, 2020).

Archive.org (1895 ed., accessed: May 15, 2023).

Archive.org (revised edition, accessed: May 15, 2023).

The Project Gutenberg (accesed: May 15, 2023).

Genre

Fiction

Mythological fiction

Target Audience

Children (particularly schoolchildren)

Cover

Retrieved from Archive.org (1895 ed.) and Archive.org (revised edition). Covers in public domain.

Author of the Entry:

Robin Diver, University of Birmingham, robin.diver@hotmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Flora Juliette Cooke

, 1864 - 1953

(Author)

Flora Juliette Cooke (b. December 1864, Ohio) was an American progressive educator and author. Cooke’s mother died when she was five, and she was sent to live with family friends who eventually adopted her in 1881. She became a teacher and in 1885 began her career at Hellman Street School in Youngstown, Ohio. Here, she formed a close bond with the school principal, Zonia Baber, at whose house she would stay when bad weather made it harder for her to travel home from the school. Baber mentored Cooke, and approved of her teaching methods, which involved creating games to keep some of her large class of children busy whilst she taught others. Cooke became school principal in 1887. From 1901 to 1934, Cooke was principal of the Francis W. Parker school in Chicago. She appears to also have been director of the School of Education at the University of Chicago.

In addition to Nature Myths, Cooke is also the author of One Year's Outlines of Work in First Primary Grade (1897?) and Colonel Parker: Paper Read Before the Parents' Association of the Francis W. Parker School (1910?). Goodreads further attributes to her name Complete Guide to Greek Mythology for Young and Old and A Brief Guide to Norse Mythology for Young and Old. These are seemingly more recent publications by A.J. Cornell Publications compiled from contributions of Cooke to World Book: Organized Knowledge in Story and Picture (1920). The same publisher has also republished the Greek sections of Nature Myths as Greek Myths for Children.

Sources:

Green, N. S., "Cooke, Flora Juliette (25 December 1864–21 February 1953)", https://doi.org/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.0900195 (accessed: April 20, 2020);

goodreads.com (accessed: April 20, 2020);

Online Books Library (accessed: April 20, 2020);

Wikipatia, tweet: twitter.com (accessed: April 20, 2020).

Bio prepared by Robin Diver, University of Birmingham, RSD253@student.bham.ac.uk

Summary

This is a collection of myths from around the world that ostensibly relate to nature, designed primarily as a reader for use in schools, although it resembles any other children’s myth anthology in form. Sometimes, the myth has been altered to make it more relevant to this theme – see "The Story of Sisyphus" in the Analysis section. The Table of Contents orders the stories according to theme, dividing them into Animal Stories, Bird Stories, Cloud Stories, Flower Stories, Insect Stories, Mineralogy Stories, Sun Myths, Tree Stories and Miscellaneous Stories. However, this is not the order in which they appear in the book, where they are not grouped by theme. The stories appear in the following order:

- Clytie.

- Golden-Rod and Aster (a story about two little girls who go missing after going to see a wise woman who probably turns them into flowers).

- The Wise King and the Bee (King Solomon).

- King Solomon and the Ants.

- Arachne.

- Aurora and Tithonus.

- How the Robin’s Breast Became Red (a story about a robin defying a bear’s attempts to put out the fire of humans in the ‘far North’).

- An Indian Story of the Robin (a story about a chieftain who forces his son to stay out in the forest waiting for a vision until the boy turns into a robin).

- The Red-Headed Woodpecker (a selfish woman gets turned into a woodpecker).

- The Story of the Pudding Stone (a giant mother makes plum pudding for her children, who play with it, impacting the landscape).

- Story of Sisyphus.

- The Palace of Alkinoos.

- Phaethon.

- The Grateful Foxes (the princess O Haru San saves a fox cub from hunters; later she falls sick and the fox’s father sacrifices his life to give his liver to heal her).

- Persephone.

- The Swan Maidens (a king’s daughters can turn into swans).

- The Poplar Tree (a man hides a pot of stolen gold in a poplar tree, which thereafter holds its branches up so nothing can be hidden beneath them).

- The Donkey and the Salt (a donkey tries to trick his master so he will not have to carry such heavy loads).

- The Secret of Fire: A Tree Story (pine trees try to hide the secret of fire from the other trees).

- A Fairy Story (giants steal a magic cap from fairies, who get it back with the help of an eagle).

- Philemon and Baucis.

- Daphne.

- An Indian Story of the Mole (a hunter sets a trap for a squirrel and accidentally catches the sun in it; the day is saved by a mole who becomes blinded by the sun in the process).

- How the Spark of Fire was Saved (animals steal fire for humans from ‘two beldams at the end of the world’).

- Balder (Odin’s son the Norse god Balder).

- How the Chipmunk Got the Stripes on its Back (the god Shiva sees a chipmunk trying to save its family who are trapped in the water beneath a tree; he saves the chipmunk family and strokes the chipmunk, leaving stripes on its back as a mark of love).

- The Fox and the Stork (Aesop’s Fables).

- Prometheus.

- Hermes.

- Iris’ Bridge (Iris’ grandfather the Ocean wants to keep her with him all the time, but the Sun insists she ‘belongs to both ocean and sky’. They then build a rainbow bridge for her to move between the two).

- Works of Reference.

Analysis

Nature Myths and Stories for Little Children is a series of myths from around the world with some connection to nature, retold for use in classrooms. Cooke defines her intended age range in her preface; the stories have been "tested and found to be very helpful in the first and third grades" (preface, p. v). She states her purpose for the work: there is a need for "stories founded upon good literature, which are within the comprehension of little children" (preface, p. III), and "myths and fables are usually beautiful truths clothed in fancy, and the dress is almost always simple and transparent". Nonetheless, she does not believe the child should be expected to interpret the meaning behind the myth: "He feels its beauty, but does not analyse it. If … he does see a meaning in the story he has entered a new world of life and beauty" (preface, page IV). She also emphasises the usefulness of myth in helping children understand high cultural references; it is "the key which unlocks so much of the best in art and literature". Finally, the myths provide important lessons. Nobody can "study these myths and not feel that … though the tales may be thousands of years old, they are quite as true as they were in the days of Homer" (preface, p. III).

Cooke’s versions of myth are often quite different from ancient versions, more so than in other children’s anthologies of the time (e.g. Francillon’s 1896 Gods and Heroes; Firth’s 1894 Stories of Old Greece; Kupfer’s 1897 Stories of Long Ago in a New Dress). Some myths are in fact virtually unrecognisable. The rather confusing "Story of Sisyphus", for example, is more recognisable by its title and the name of the character Sisyphus than by the story. It tells of Little White Cloud, the much-loved daughter of the Ocean, who wanders off whilst her father is asleep, goes for a ride on the sun’s rays and disappears. Sisyphus, a lonely giant, feels sorry for Ocean and helps him out in return for water. The Sun is angry that Sisyphus told on him and orders him to forevermore push stones out of the sea and onto the shore; however, this is not presented as a sad end for Sisyphus as he has longed for "a great work to do" (p. 35) and this gives him an opportunity to be helpful. Perhaps this alteration is due to Cooke finding the original themes of the myth and its cruel ending distasteful, but wanting to include it in order to introduce the child to the well-known character of Sisyphus in some form.

Other stories are not nearly as different from ancient versions, however; for example "Phaethon" sticks fairly closely to Ovid’s narrative.

Many of the changes Cooke makes to the myths seem designed to render them more like fairy tale and folklore, a common trend for myth anthologies of the time (see e.g. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 1851 Wonder Book for Girls and Boys ; Blanche Winder’s 1923 Once Upon a Time: Children’s Stories from the Classics). For example, Demeter falls into a deep sleep for the half of the year Persephone is not there, reminiscent of Sleeping Beauty and other fairy tales, and this is what causes winter. As might be expected from the title of the work, nature and natural themes are emphasised.

Similarly to Nathaniel Hawthorne’s influential children’s anthologies (1851; 1853), the divinity of the gods is played down without being completely obscured, presumably to avoid contradicting Christian teachings. Demeter is described as having "the care of all the plants, fruits and grains in the world" (p. 48), which mimics her mythological role without explicitly calling her a goddess. Hades is the possessor of a loosely defined "land of darkness" (p. 49). Apollo and Helios are fairly literal forms of the sun itself.

In the world of Cooke, people also appear to like these gods. In the case of Demeter, for example: "They loved the kind earth-mother and gladly obeyed her." (p. 48).

The stories are told in simple language, often with one line allocated per sentence. This means the anthology resembles Mary Helen Beckwith’s In Mythland anthology of 1896, which is also aimed at very young children and also appears to be by a schoolteacher. In their retellings of the Daphne and Apollo myth, these two authors at one point use almost identical phrasing. Beckwith portrays Daphne as a charming but wild child, saying "The birds and bees were her playmates. She did not care for other friends" (p. 21). Cooke portrays Daphne as a charming but isolated child, and states "The trees and the forest animals were her play-fellows, and she had no wish for other friends" (p. 75). Since in ancient versions Daphne is a hunter of nature not a playmate, it is possible this similarity of phrasing between Beckwith and Cooke comes from common use of a contemporary myth handbook.

There is a general tone of compassion and kindness to Cooke’s anthology. Characters are presented sympathetically, acts of generosity are rewarded and relationships between characters, particularly family members, are warm and loving. The non-Greek story "The Grateful Foxes" for example rewards the heroine for her kindness to a fox cub and desire to preserve a loving fox nuclear family. In the Clytie retelling, Apollo is referred to as ‘the great kind king’, and his smile when he rises allows nature to run smoothly.

Whilst we might stereotypically view the nineteenth century as a time that encouraged women to make others the centre of their worlds, it is interesting that some of Cooke’s alterations actually result in female characters more focused on their own wishes and identity than in ancient versions. In the Clytie retelling, Clytie does not desire Apollo sexually. Instead, her obsessive watching of him is due to her admiration of him and desperate desire to be him. Rather than a nymph pining for the love of the sun god, therefore, we have a nymph who desires the god’s greater power for herself. When she is turned into a sunflower, the narrative suggests this is a happy ending for Clytie because she partially has her wish to be like Apollo and make people happy when they see her.

Likewise, in many more recent Persephone retellings, Persephone is made to sympathise and identify with her captor Hades, even sometimes coming to value his wishes almost as much as her own (see e.g. McCaughrean’s 1992 The Orchard Book of Greek Myths; Brack, Sweeney and Thomas’ 2014 Brick Greek Myths). In Cooke’s older retelling, Persephone does not do this. Instead, it is Hades who empathises with her and voluntarily releases her for half the year. Female characters are also not criticised for expecting loyalty and help from others; Demeter is portrayed as an admirable, kind and loving woman, but is indignant when she believes nature has forgotten Persephone and gone back to thriving without her. Cooke’s anthology in some ways takes a more positive view of female autonomy and self-interest than do recent works.

As in the anthologies of Hawthorne, there are attempts to connect the actions of the characters to relatable moments of nineteenth century childhood. For example, the children of Aeolus are shown being good, productive family members: "There were no idle children in the family of Aeolus. They swept and dusted the whole world. They carried water over all the earth. They helped push the great ships across the ocean. The smaller winds scattered the seeds and sprinkled the flowers, and did many other things which you may find out for yourselves. Indeed, they were so busy that Aeolus was often left alone in his dark home for several days" (p. 97). They are also shown singing songs.

Whilst this might not be an appealing vision of mythical childhood for child readers, Cooke also makes use of her nature theme to fashion beautiful fantasy homes out of natural materials for children such as Clytie and Daphne. Clytie’s ocean cave home is decorated with pearls and shells, and holds chairs of amber and moss cushions, gardens of seaweed and starfish and dresses of soft sea lace. She has goldfish and turtle horses and rides around in a shell carriage. Such settings are probably intended as wish-fulfilment for children, in accord with the theme of appreciating nature.

Cooke lists her sources at the back of the book, which are a number of myth handbooks, including Bulfinch’s Age of Fable and Cox’s Mythology of Aryan Nations. She also includes a further reading list to encourage children’s appreciation and knowledge of nature. My Leopold Classic Library edition includes a number of adverts for other children’s books in the final pages, seemingly copied over from the original edition.