Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

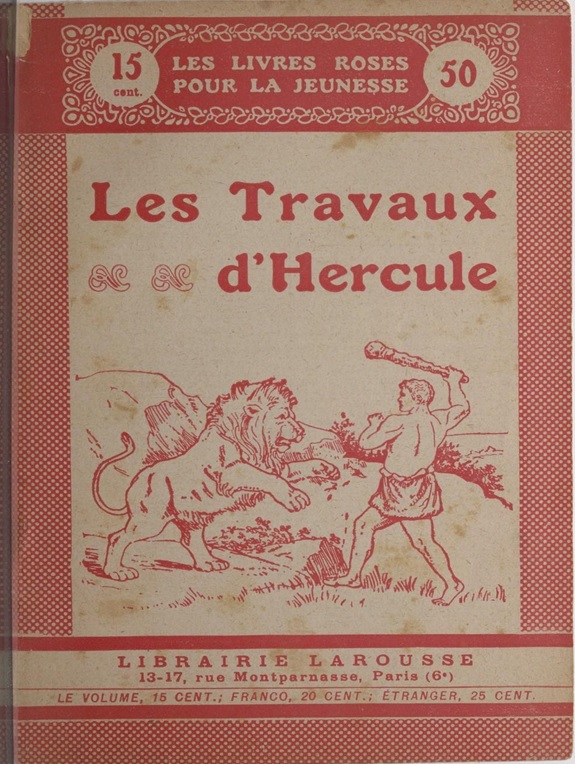

Les Travaux d'Hercule, adapt. pour les enfants par Mlle Jeanne Bloch, "Les livres roses pour la jeunesse" 50. Paris: Larousse, 1911, 56 pp.

Available Onllne

gallica.bnf.fr (accessed: September 1, 2020)

Genre

Adaptations

Myths

Short stories

Target Audience

Children

Cover

Cover in public domain (accessed: September 9, 2020).

Author of the Entry:

Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Daniel A. Nkemleke, University of Yaoundé 1, nkemlekedan@yahoo.com

Jeanne Bloch (Author)

Jeanne Bloch (unknown, 18..–19..) was an agrégée de l'université*, professor at the famous Collège Sévigné in Paris, the first French non-denominational (private) high school for girls opened in 1880 by the group of founders of the Société pour la propagation de l'instruction parmi les femmes. Since 1919, a kindergarten was added to the school which remains still an active and highly praised private establishment. A number of well-known French scholars and intellectuals taught at the Collège, among them the outstanding Hellenist, Jacqueline de Romilly (1913–2010), member of the Académie Française and Collège de France. Jeanne Bloch was the author of many French adaptations for Les livres roses pour la jeneusse - collection for children published by Larousse, such as: Un été au pays des écureuils: histoire de monsieur Moustache et de son chemin de fer aérien (1910), La conversion de Catherine (1911), Contes de la Chine et de l'Inde (1911), Nouvelles aventures du Vieux Frère Lapin (1911), Le roman d'un lutin; suivi de La tortue bavarde: conte de l'Inde (1911), Les travaux d’Hercule (1911), Persée, le vainqueur de la Gorgone (1911), La Tempête et Comme il vous plaira (1911), Récits et légendes de la Rome antique (1912), Histoire de Gallus, Poulette et Glouglou (1912).

* According to the French education system. More here (accessed: September 9, 2020).

Bio prepared by Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Sequels, Prequels and Spin-offs

In the series, Les travaux d’Hercule are preceded by No. 49, L’Escapade de Boulboule, and followed by No. 51, Les Six Lévriers blancs, both unrelated to classical Antiquity.

Summary

Les Travaux d’Hercule is an adaptation for children published as no. 50 of Les livres roses pour le jeunesse (Pink Books for Youth) Collection Stead of Librairie Larousse. The Collection Stead is a series fascicles, prepared especially for children, and includes fables, myths, legends, fairytales and various stories, also based on literature for grownups (e.g. Shakespeare’s The Tempest and As You Like It or Scott’s Ivanhoe). The collection was published in English, then in French by William Thomas Stead (1849–1912), an English journalist and philanthropist who died in the Titanic’s shipwreck. The authors of the provided texts are called adaptateurs, the names of illustrators usually do not appear, though the series contains a unified graphic design. The booklet The Labors of Hercules features 49 refined detailed engraved illustrations, which are a great asset for children since they not only show the characters in action but can also be colored by the reader.

In the short preface to the young reader there is a scene which suggests that a child who does not know who Hercules was is just an ignorant and that children should be familiar with ancient mythology which is an important part of contemporary culture. That’s why this particular booklet was created as a continuation of previous ones connected with ancient Greece.

The booklet is entirely devoted to the myth of Hercules and was published based on no. 27 of Books for the Bairns, the English version by Charles Kingsley entitled The Labours of Hercules, also in the Collection Stead. Stead’s idea accepted by the publisher was to provide French children with a possibility of a simultaneous reading of the two versions in order study and improve English.

Beyond the main text about Hercules, there is also an occasional page récréations with homework tasks (quizzes, charades, etc.) and solutions of the tasks given in the previous booklet of the fascicle, then the section La physique de la jeunesse describing how a barometer works and the section with readers correspondence.

In the spirit of educational and moral edification, Jeanne Bloch addresses the final paragraphs directly to the child reader: "Et pour vous, enfants, voici l’enseignement que vous pouvez tirer de l’histoire d’Hercule." [And for you, children here is a lesson you can learn from the story of Hercules]. Since children cannot clean the stables of Augeas, they can instead weed a garden or tidy up a house and while there is no Cerberus, they can take joy from overcoming bad temper or fits of anger.

The booklet contains the story of Hercules’ life organized in five chapters. Chapter one describes his infancy and youth including the killing of the serpents, education by an old Centaur and marriage to the daughter of king of Thebes as a reward for defeating a ferocious lion, ending Hercules’ madness and eventually his killing of his wife and children. The protagonist goes to the Oracle of Delphi and then to Tiryns ruled by the cruel king, Eurystheus, to serve him as ordered by the oracle. In chapter two, the first four of Hercules’ labors are described: the Nemean Lion, the Lernaean Hydra, the Ceryneian Hind, and the Erymanthian Boar. The chapter three presents the cleaning of the Augean stables, frightening the Stymphalian birds with a rattle, defeating the Cretan Bull with bare hands and bringing Mares of Diomedes to Eurystheus. Chapter four focuses on the last four labors: (1) imprisoning of the queen of the Amazons to obtain her belt, (2) the journey across the Libyan desert with the lift on Helios’ chariot to get the cattle of Geryon (during which he established the Pillars of Hercules and defeated Cacus near the Aventine Hill of future Rome), (3) gathering the Golden Apples from the garden of the Hesperides – meeting Atlas and holding up the heavens, and eventually, (4) the capture of Cerberus. In chapter five, Hercules is freed after twelve years of service to Eurystheus and visits Olympus where Jupiter tells him to return to earth and liberate her from evil. Then he serves three years as a “maid” to a barbarian queen doing house chores. After that he marries the princess, Deianeira, who, since the failed attempt at kidnapping her by the centaur Nessus, keeps a tunic dipped in the centaur’s blood allegedly able to revive Hercules’ love for her, in case he would leave her. Some years later, when Hercules does abandon his wife and children for another woman, he puts on the tunic but the poisonous blood of Nessus only causes him great suffering. Anticipating his death, Hercules mounts the funeral pyre and when he dies, solely his ashes remain.

Analysis

The adaptation of the myth shows Hercules’ whole life, from his infancy to death, omitting some plots and adding some others. This stems potentially from the intention to adapt the myth making it more approachable for children born at the beginning of the 20th century. The booklet omits the story of Zeus seducing Alcmene disguised as Amphitryon and the divine origin of the hero: both twins Hercules and Iphicles are presented as sons of Amphitryon. By passing over the issue of paternity, the author also removes as a consequence the motive of Hera's anger: the snakes strangled by Hercules in infancy are not sent by the goddess, the baby kills them with his bare hands because of his strength, not because his father was a ruler of Olympus and Hera breastfed him thanks to ruse of Athena, his protector. Hercules is described not as a naughty and impolite schoolboy, but his main feature is a short temper. He destroys everything around him when wrathful. While he always regrets his misdeeds later, the damage is already done and impossible to undo. His anger one day makes him kill his master of music unintentionally and he is sent to a school led by an old centaur. Even as a young adult, he still suffers from fits of anger; eventually as a result of his madness, he perceives his wife and children as beasts and kills them. Crazed with grief and pain, he goes to the Delphic oracle. The oracle, speaking directly, sends him to the cruel and ruthless king Eurystheus of Tiryns to serve him for 12 years in order to earn expiation and redemption. This ends the youth of the protagonist and launches his life of an invincible hero.

The 12 labors reveal a role model for a hero facing difficult, almost impossible quests: brave, fearless, strong, but also clever and cunning to find solutions to problems by using not only physical strength, but also intelligence. The adventures of Hercules are to amuse and entertain the young reader but also show the hero’s transformation. After finishing the labors Jupiter himself tells the protagonist that he has finally redeemed his past and praises him for his achievements and moral attitude. Hercules is sent to Earth to undertake even more difficult quests: to punish the malicious, to protect the weak, to console the afflicted, to stay strong while suffering, to control his anger, even sometimes to fail and patiently endure the failure. The hero’s failure is described when one day he finally allows himself to resort to violence and commits a bad deed. This makes gods angry and as a consequence inflicts another punishment of three more years of degrading service to a barbaric queen, who strips him of his lion skin to wear it herself and humiliates him as much as she can. The child reader can see the real man in a fierce hero, who tries to be better and fights to control his undesirable trait, but also sometimes fails, regrets and bears the consequences. Then, even the greatest hero must accept the punishment, but after the penalty is completed, the man can lead a normal life, marry and start a family. The tragic final scene is again a consequence of the hero’s choices, when he once more crosses the line of what is right and hurts his wife’s feelings.

The story does not end with deification, not even with immortality or marrying a goddess. There is no motif of Hera’s revenge, no expedition for the Golden Fleece, no choice at the crossroads. The entire story is constructed to show how getting angry can badly affect a person, even the greatest one. The final sentence directly explains to the children that if we don't have to go to hell to bring Cerberus, at least we can silence the noises of a bad mood, drive it from our heart and our home ("Et si nous n'avons pas à aller jusqu'aux enfers pour en ramener Cerbère, au moins pouvons-nous faire taire les grognements de la mauvaise humeur, la chasser de notre coeur et de notre maison."*).

As references to the ancient Greek world are not obvious and familiar to a child, the author puts some informative explanations in the main text or in footnotes. For example she describes who the centaurs were, what Hercules learnt at school, what an Oracle was and how it functioned, why Hercules was always depicted in a lion's skin protecting his head and body, how the Greeks buried the dead, where Thrace was (part of the sultan’s Turkey in those days), who Amazons were, how Perseus transformed Atlas into stone, how Pluto’s realm of the dead – the Greek Hades – worked. It is worth mentioning that the French author writes about the mythical Greek world, but without consistently using Greek proper names. In fact most of the names are Greek, but there are some Roman equivalents used instead, such as: Hercules, Juno, Jupiter, or Mars, whose name in a footnote is explained as a Greek god of war ("Mars, dieu de la guerre chez les Grecs").

* J. Bloch, Les Travaux d’Hercule, Paris: Larousse, 1911, 56.

Further Reading

De Blacam, Aodh, "Books for the Bairns", The Irish Monthly 74. 876 (1946): 265–273 (accessed: September 9, 2020).

Wood-Lamont, Sally, W.T. Stead’s “Books for the Bairns”, Salvia Books, Edinburgh, 1987 (accessed: September 9, 2020).