Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Maria Dynowska, Po złote runo. Kraków: Księgarnia Nauka i Sztuka, 1939, 227 pp.

Available Onllne

polona.pl (accessed: October 19, 2020)

Genre

Action and adventure fiction

Novels

Target Audience

Crossover (Children, teenagers, young adults)

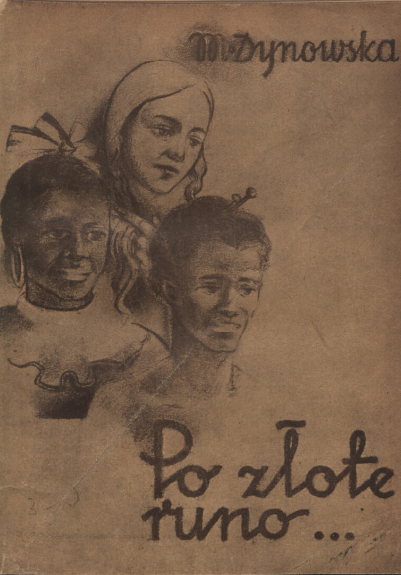

Cover

Retrieved from polona.pl, public domain.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Daria Pszenna, University of Warsaw, dariapszenna@student.uw.edu.pl

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Maria Dynowska

, 1872 - 1938

(Author)

A philologist and author of many books for children. Born into a family of Warsaw intellectuals. Began her higher education at the Flying University, an underground teaching system for women under Russian Partition in Warsaw; then studied in Cracow and later returned to Warsaw and began teaching underground courses. During WW1, she moved again to Cracow where she remained until her death. She did not confine herself to writing books but was as well a social activist. Associated with the Polish Radio; member of Stronnictwo Narodowe [National Party].

Source:

"Dynowska Maria", in: Ewa Korzeniewska, ed., Słownik współczesnych pisarzy polskich, vol. 1: A–I, Warszawa: Panstwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1963, 476–477.

Bio prepared by Zofia Górka, University of Warsaw, vounaki.zms@gmail.com

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

Two historic episodes provide the background for the story. The first is connected to a series of uprisings in partitioned Poland that failed to liberate the country from foreign rule: the November Uprising (1830), the insurrection in Galicia (1846) and the Spring of Nations as it played out in the Polish territories (1848). The second is related to the gold rush in the eastern part of Australia in the 1850s. Incidentally, the geologist, who in 1839 first discovered the precious metal in Australia and later climbed the highest peak of the continent (Mount Kosciuszko) was a Pole, Paweł Edmund Strzelecki.

The characters are a group of Polish emigrants, ex–insurgents: col. Antoni Komornicki, major Seweryn Orlinski, Stanisław Downar, and Bolesław Szeliski. They must escape their homeland to avoid repercussions from foreign rulers. Australia seems a possible new home, especially because they learn about large deposits of gold discovered there — a gold rush could provide them with a good life. The men are accompanied by Halszka Rymsza (the daughter of colonel Komornicki’s deceased friend) and her companion Clara Bird.

Diaries of one of the members of the expedition, which took place in the years 1852–1856, were the inspiration for the book. The diaries provide extensive descriptions of Australian reality: flora and fauna, gold diggers’ operations, the physical appearance of the natives and most of all, an array of dangers threatening the foreigners.

Analysis

Seeking the Golden Fleece is not a novel based on Apollonius’ of Rhodes Argonautica and is not even set in a mythical world. The title, initially confusing, can be understood as a metaphor for a dangerous quest and a difficult journey to achieve an impossible goal. However, the gold found in Australia by Strzelecki is presented as an object of desire, though getting rich is not shown to be a goal in itself. Just like the mythical Jason, the protagonists travel with an assembled company of friends on a special ship, here the biggest steamer, Great Britain (see here, accessed: October 19, 2020). Like in the myth, they need to get the gold, the means to obtain a higher goal. Full of risk and danger, the quest for the precious ore is a necessity for Dynowska’s characters and the only possible solution to their difficult situation. Starving and jobless in London, they eventually decide to work hard in Australia, firstly to survive, and then, once they obtain amnesty from repressions, to return like Jason to their beloved homeland, which is their real dream.

References to Antiquity appear not only in the title metaphor but also at the text level as an integral part of culture and the education of the ordinary people of that era. One of the characters, Bolek Szeliski, after finishing work as a dock worker in London, has another part-time job: as a university graduate, he teaches Latin to English boys using Julius Caesar as his text*. He also compares Halszka to Xanthippe, who is a symbol of a nagging, unbearable woman, when the girl reacts to Downar’s jokes by pulling his hair**. Not only Bolek incorporates ancient culture into his language, but also major Orliński uses Latin maxims, like Contra spem spero (asked about a future in which Poland would be an independent state, p.53, accessed: October 19, 2020). Last but not least, antiquity is present in the mythological setup of an event prepared by the steamer’s crew on the occasion of crossing the equator. The day before the crossing, the captain warns passengers that Neptune would visit them in person and that he must get an honourable reception. On the day that they cross the equatorial line (“visible” in the lunette thanks to a hair stuck to the telescope glass), the ship is all cleaned up and decorated. The captain reads the letter from Neptune, who promises to come before the evening. Eventually, the ruler of the sea appears in a procession, surrounded by a cluster of tritons. He looks like a grey-haired, long-bearded elder man, with a trident in his hand, his most recognizable attribute. There is also a minor linguistic reference to Antiquity in the nickname given to the character of Giovanni Falcone, an American-Italian globetrotter. Friends call him Kosmos, which comes from Greek. Κόσμος can mean first of all “world” or “order”, but also “people” and “mankind”, not only “universe”. Such a meaning corresponds with the character, as Falcone travels across the world: Italy, America, Asia, eventually, Australia and then, when he marries Klara, it is clear that they would both travel the world guided by their curiosity and desire for adventure.

Interestingly, the text displays stereotyped attitudes towards other nations, tribes, and social groups typical for either mid-19th century, the time of the action, or the 1930s when the book was written. However, a tented settlement of gold prospectors is compared to the Tower of Babel, a mix of different nationalities and professions. Prussians met in Australia are described as damned redheads, vulgar liars, and deceivers. The first indigenous Australian met on the way to Forest Creek also brings up a stereotype of Aborigines, perceived as nasty, scary, lazy, and greedy (p. 72). Tatika, a native Australian rescued by Halszka from a viper’s bite, is called “a stupid black fellow” or “this monstrum” by the others. The Polish group’s opinion of Tatika changes when he starts to help the girl who saved him, works hard, and, because of his loyalty, finally proves his value: he recovers and saves a kidnapped Halszka. Szeliski then says about him with appreciation: "we were overawed by this savage’s intellect. God, protect him. Compared to him I am an idiot with my university [education]"***, but the others still despise him and his people and use harsh, contemptuous words, such as: "Strange that he works for you. An Australian likes to steal but it’s difficult to make him work"****, "they are willing to murder for profit, and fiercely fight between themselves"*****. Halszka finds such opinions unjustified as she becomes friends with Tatika and treats him as a “noble savage”. Eventually, despite the initial negative opinion about indigenous Australians, the character of Tatika is presented very positively but still not as an equal. The man is just, loyal, diligent, intelligent, open-minded, eager to learn – thanks to his sense of gratitude, wisdom, courage, and knowledge of nature, he tracks the kidnapped girl and brings her back. He adopts clemency sparing his enemy’s life in order to please her. When he dies in a dramatic scene, the only thing he cares about is that “Miss Bessy (as he calls Halszka) [is] safe” (p. 139). The loss of the Aboriginal’s life underlines the tragedy of native people who even when recognized as noble are still considered inferior and unworthy of respect by most of the European settlers in the 19th and mid-20th centuries.

* "…kształcił w łacinie tych urwipołciów, których mu poczciwy Smith naraił." p. 14;

"moje angielskie nygusy przestaną gnębić Juliusza Cezara za jakie dwa tygodnie", p. 14.

** "Z damami nie walczę,(...) wolę uniknąć spotkania z Ksantypą." p. 39.

*** "…zawstydził nas ten dziki swym rozumem. Daj mu, Boże, zdrowie. Idiota jestem wobec niego z moim uniwersytetem", p. 126.

**** "Dziwne, że pracuje u was. Australijczyk lubi ukraść, lecz do roboty zapędzić go trudno." p. 133.

***** "…umieją zamordować dla rabunku, umieją straszne walki prowadzić między sobą." p. 134.

Further Reading

[Baginska–Mleczak, Jolanta], Paweł Edmund Strzelecki. Society of Unity with Poles Abroad “Polonia”, Poznań Branch, Edward Raczyński Municipal Public Library, Poznań: Oddział Towarzystwa Polonia, 1988 [a bilingual, English– Polish edition].

Dybkowska, Alicja, Jan Żaryn and Małgorzata Żaryn, Polskie dzieje od czasów najdawniejszych do współczesności, Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1995, 191–196, 204–205.

Paszkowski, Lech, Sir Paul Edmund de Strzelecki: Reflections on his Life, Melbourne: Arcadia Australian Scholarly Publishing, 1997, 57–178.

Zdrada, Jerzy, Historia Polski 1795–1914, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 2005, 138–200, 217–220, 334–348, 353–361.