Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Nathaniel Hawthorne, Tanglewood Tales for Girls and Boys. Boston: Ticknor, Reed & Fields, 1853, unpaginated.

ISBN

Available Onllne

gutenberg.org(accessed: October 20, 2020)

Genre

Didactic fiction

Mythological fiction

Target Audience

Children

Cover

Cover of the edition of Maynard, Merrill, & Co., New York, from 1898. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, public domain (accessed: December 15, 2021).

Author of the Entry:

Miriam Riverlea, University of New England, mriverlea@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

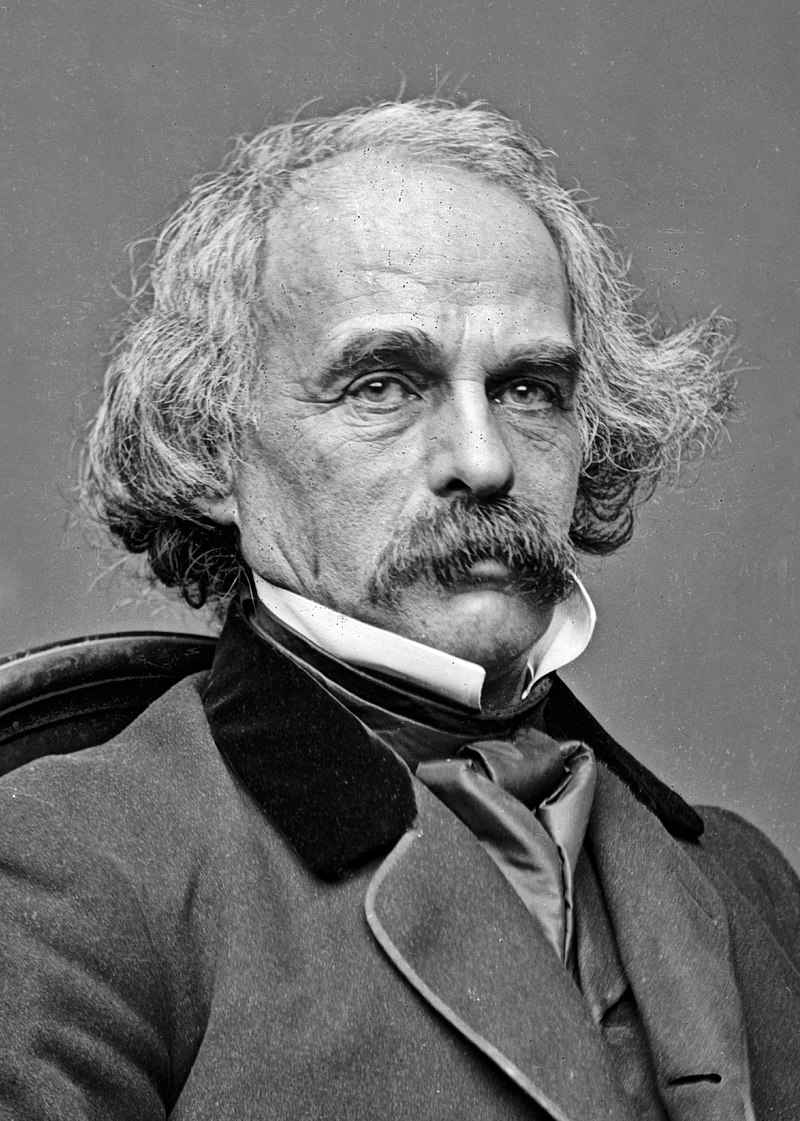

Retrieved from Wikipedia Commons, public domain (accessed: December 8, 2021).

Nathaniel Hawthorne

, 1804 - 1864

Nathaniel Hawthorne was born in Salem, Massachusetts, on July 4th, 1804, into a well-established Puritan family. One of his ancestors, John Hathorne, was a judge during the Salem Witch Trials of the 1690s. Although Nathaniel added the ‘w’ to his surname to distance himself from this branch of the family, his Puritan heritage had a deep influence on his writing. His best-known novels The Scarlet Letter (1850) and The House of the Seven Gables (1851) explore the themes of guilt and repentance, sin and retribution, and are widely regarded as classics of American literature.

Hawthorne’s ambition to be a writer was established during childhood, when a leg injury kept him bedridden for several months, with books as his only source of entertainment. His father, a sea captain, died of yellow fever when Nathaniel was four, and the family was taken in by his mother’s wealthy brothers, who went on to support his studies. After completing university Hawthorne began self-publishing short stories, including Twice Told Tales (1837) and in 1841, Grandfather’s Chair, a history of New England written for children. In 1842 he married Sophia Peabody, an artist with an interest in transcendentalism, and they went on to have three children.

A Wonder Book for Girls and Boys (1851) and its sequel, Tanglewood Tales (1853), were written during Hawthorne’s most productive period, following the financial and critical success of his novels. In the Preface to A Wonder Book, Hawthorne describes the experience of writing the book as “a pleasant task…and one of the most agreeable, of a literary kind, which he ever undertook.” In later life his writing became disordered, and after an extended illness he died in his sleep on May 19, 1864.

Bio prepared by Miriam Riverlea, University of New England, mriverlea@gmail.com

Translation

Spanish: Cuentos de Tanglewood, trans. Marta Salís, Barcelona: Alba, 1999.

Chinese: Tanglewood Tales, trans. CNPeReading, 开放图书馆 ebook

Polish: Mity greckie, trans. M. J. Lutosławska, Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy "Biblioteka Polska", 1937, 1947, 1948; Warszawa: Nasza Księgarnia, 1960.

Opowieści z zaczarowanego lasu: Mity greckie, trans. Krystyna Tarnowska and Andrzej Konarek, Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy „Nasza Księgarnia”, 1973, 1980, 1987, 1988, 1989; Warszawa: Votum, 1992.

French: Tanglewood Tales, Boston: Osgood.

(Based on information from worldcat.org – not all details available, accessed: October 20, 2020)

Summary

Tanglewood Tales is the sequel to Hawthorne’s first volume of Greek myths for children, A Wonder Book for Girls and Boys. In the Introduction to this book, a precocious young storyteller Eustace Bright returns to Tanglewood Manor to visit Nathaniel Hawthorne, and they discuss the success of their recent publication, which, according to the fiction, Eustace composed and Hawthorne edited. Now Eustace presents his friend with a second collection of six stories. Although this volume does not feature the cast of botanically named children from A Wonder Book – Cowslip, Buttercup, Primrose and the rest – for whom Eustace performed, the tone, style and imagery of the prequel is retained.

The opening tale, entitled "The Minotaur", tells the story of the hero Theseus. It begins with an account of his childhood in Troezene and describes how he eventually grows strong enough to lift the rock and retrieve his father’s sword and sandals. His encounters with Procrustes and Scinis on the road to Athens are only briefly described, but his arrival at his father’s court, and narrow escape from the machinations of the enchantress Medea, are recounted in detail. Having been recognised and accepted by Aegeus, Theseus volunteers to join the group of 14 sacrificial youths who are sent to Crete as an annual tribute. As they reach their destination they pass Talus, the brass giant, who patrols the entrance to the Cretan harbour. Evil King Minos receives the Athenian prisoners, and his daughter Ariadne is impressed by Theseus’ brave spirit. While the other youths and maidens sleep, Ariadne leads Theseus to the entrance of the labyrinth. She returns his sword to him and gives him a ball of silken string to help him find his way. After a fearsome battle Theseus catches the monstrous Minotaur off guard and cuts off his head. He follows the thread out of the maze where Ariadne is waiting. After awakening his companions, Theseus races for the harbour before Minos discovers what has happened. Theseus entreats Ariadne to accompany them, but she insists on remaining behind with her father, who "is old and has nobody to love him". As the vessel sails between the legs of the giant Talus he strikes out at them but loses his balance and tumbles into the sea. The young people are so busy celebrating as they return to Athens that Theseus forgets to honour the promise he made to his father to raise a white sail as a signal of victory. Keeping vigil on the cliffs, Aegeus sees the black sails and in his grief hurls himself into the ocean below. Theseus arrives home to discover the tragedy, but sends for his mother and becomes a wise ruler of Athens.

The next story, "The Pygmies", tells of the unique friendship between the giant Antaeus and the million or so "curious little Earth-born people", the Pygmies. Antaeus is also the son of Gaia, and derives strength whenever a part of his body is in contact with the earth. Despite their differences in size and occasional accidents, Antaeus and the Pygmies have lived in harmony for generations. When he is able, the huge man assists the Pygmies in their war with the cranes, who feast on the tiny people when they can catch them. Then Hercules passes through their territory on his journey to retrieve the Golden Apples from the Garden of the Hesperides, his eleventh labour. Jealous of his strength and heroic reputation, Antaeus challenges him to a fight. As they battle each other with their enormous clubs, the Pygmies’ city is laid to waste. When they begin to wrestle, Hercules discovers that his opponent’s strength abates as he loses contact with the ground. He lifts Antaeus high in the air, and after five minutes, he expires completely. While Hercules takes a nap to recover from his exertions, the Pygmies gather to avenge their friend. They set his hair on fire and fire volleys of tiny arrows at him. Having already seen all manner of monsters and amazing sights on his wanderings, Heracles is amazed by their minute stature. He declares himself vanquished, and taking giant strides, quickly departs from their land.

"The Dragon’s Teeth" is the story of the little girl Europa’s abduction by an enchanting white bull, and the long pilgrimage that her three brothers Cadmus, Phoenix and Cilix make as they search for her, joined by their childhood friend Thasus and their mother Queen. After many years wandering the world, one by one the companions give up the fruitless quest and found their own cities. Before Telephassa dies, she tells Cadmus, the last of the searchers, to visit Delphi, where the oracle instructs him to stop seeking Europa and follow a cow. Where the creature lies down, he should found his own city. Accompanied by a loyal band of followers, Cadmus follows the creature to a fertile plain. But a ravenous dragon who lives there devours his friends before he manages to slay it by leaping down its throat. Alone once more, Cadmus hears a voice instructing him to pluck out the dragon’s teeth and sow them in the ground. From these strange seeds sprout an army of fierce warriors, and when Cadmus tosses a stone in their midst they begin to fight each other. The battle is brutal and soon only five survive. Heeding the commands of the strange voice, Cadmus orders them to sheath their weapons, and asserting his kingly authority, instructs them to build his city. In a single day they lay the foundations and construct their own quarters, and while they sleep a magnificent marble palace for Cadmus springs from the soil. Inside is a beautiful woman, Harmonia, "a daughter of the sky, who is given you instead of sister, brothers, and friend, and mother." The story ends with a description of the happy life led by the King, Queen, and many little children, who appear mysteriously and are doted upon by the dragon warriors. To help civilise them Cadmus invents the alphabet and ensures they learn to read. Nothing more is said about the lives of the other brothers in their own cities, nor about the fate of Europa.

In "Circe’s Palace", Ulysses and his crew land on an unknown island, having already encountered many horrors on their long journey home from Troy. The men are weary and wretched and soon grow hungry. Ulysses explores the island and spies an incredible palace in its centre, but a little bird warns him off approaching it. The greedy crew grow ever more ravenous and Ulysses finally consents that half the group should ask the owner for help. Led by cautious Eurylochus, the crude band of men are received by Circe and her servants, who snigger behind their hands while pretending to honour the guests. After an extravagant feast, at which the men make utter pigs of themselves, Circe uses her magic to reveal their true natures, and transforms them into swine. Eurylochus, who had hidden outside, rushes back to Ulysses to report what has happened. He enters the palace, but not before he meets the little bird again, and has an encounter with Quicksilver, who furnishes him with a magic flower that will prevent the witch’s enchantment. Circe welcomes him into her home, and presents him the best wine she has. Sniffing the flower at the same time, he drains the cup. Circe expects to he transformed into a pig, lion, wolf or fox, but he instead draws his sword and demands that she release his companions. Though the spell is reversed, they retain some of their swinish qualities, and enjoy the pleasures of life with Circe before their next adventure.

"The Pomegranate Seeds" is a retelling of the story of Demeter and her daughter Persephone, here referred to by their Roman names Ceres and Proserpina. The retelling follows the Homeric Hymn to Demeter closely. Ceres is a devoted mother, but has to leave her daughter alone to tend the crops. Proserpine forgets to adhere to the strict instructions to stay out of the meadow. She is delighted by an outrageous shrub that flower adorned with many different blooms, but when she plucks it, a chasm in the earth is revealed, from which Pluto rides forth on his grim horse drawn chariot. He is well dressed and handsome, but sullen and moody, and entices her, first gently, and then with brute force, to accompany him. Ceres is far away and does not hear her daughter’s cries for help. Pluto takes Proserpine on a tour of the Underworld, seeking to impress her with its great riches, and introduces her to three-headed, dragon-tailed Cerberus, who is as frisky as any normal puppy, and tries to tempt her with rich, elaborate dishes. But Proserpine remains unmoved and pines for her mother and their simple life on earth. Ceres searches for her daughter for many days, pausing neither to sleep nor eat. She receives little information, but is joined by the miserable Hecate. At Eleusis she becomes nursemaid to the prince Demophoon, but her attempt to make the boy immortal is interrupted by the Queen. In grief at her losses, Ceres causes a great famine. Quicksilver is dispatched to resolve the situation with Pluto. Proserpina has grown somewhat fond of him, and as she is about to depart she sneaks a nibble on a pomegranate that has been left on the table. Pluto suspects nothing, but Quicksilver observes what she has done, and back on earth, Ceres’ torch, which has burned day and night for six months, flickers and goes out. Mother and daughter are joyfully reunited, but when questioned Proserpine admits to sucking on the six seeds, which ties her to the underworld realm for half of each year. She seems happy enough at the thought of making another happy.

The final story in the collection is "The Golden Fleece". As a baby Jason is sent away by his parents to be schooled by the Centaur Chiron. When he comes of age, he returns to Iolcus to challenge his uncle Pelias who has usurped the throne. On the way he has to cross a fast moving river. On the bank is an old woman, accompanied by a peacock, who commands him to carry her across. Though initially unwilling, Jason does her bidding, losing one of his sandals in the process. Arriving at the palace, King Pelias greets him warily, having been given a prophesy from the Speaking Oak of Dodona, that a man wearing only one sandal will claim the throne. Pelias baits Jason into going on a dangerous quest to retrieve the Golden Fleece. The Talking Oak advises him on how to build a ship and offers one of its own branches to be carved as the Argo’s figurehead. Many heroes – Hercules, Theseus, Orpheus, Castor and Pollux and Atalanta – join Jason on the quest. The Argonauts face many dangers on their journey to Colchis, where they are received by King Aeetes and his daughter Medea, who offers to help Jason with the challenges set by her father. Having been taught witchcraft by her aunt Circe, she advises him how to yoke the fire breathing bulls, and hands him the dragon’s teeth (leftover from the story of Cadmus) to sow the field. As in the earlier story, at Medea’s urging Jason throws a stone amongst the warriors and they slay each other in fierce combat. They defy Aeetes, and while Medea puts the dragon to sleep, Jason steals the fleece. The story ends with their hasty departure from Colchis, accompanied by the song of Orpheus.

Analysis

As in A Wonder Book, Hawthorne reflects on the challenges of adapting classical myths for child readers:

"These old legends, so brimming over with everything that is most abhorrent to our Christianized moral sense, some of them so hideous, others so melancholy and miserable…was such the material the stuff that children’s playthings should be made of! How were they to be purified? How was the blessed sunshine to be thrown into them?"

He allows his character (a literary device—the fellow-storyteller), the young Yankee student Eustace Bright, to defend his project. The young man maintains that the "objectionable characteristics seem to be a parasitical growth, having no essential connection to the original fable", and that it is the purity of the storytelling performance, and the innocence of the young audience, who enable the true essence of the myth to emerge. With a cast of brave princes, evil kings, malevolent witches, giants and dragons, these stories resemble fairy tales. This collection is less didactic than A Wonder Book, but it nevertheless models the virtues of loyalty, courage, and friendship, and derides greed, gluttony and malevolence.

Hawthorne remains coy about sex, though given the period in which he is writing, this is unsurprising. After living together in their wonderful palace, Cadmus and Harmonia are joined by many little children, "but how they came thither has always been a mystery to me", the author remarks. Similarly, other romantic relationships are reconfigured as chaste and naïve. Hades abducts Proserpine to brighten up the Underworld, not as his wife, but "as a merry little maid". Other relationships are privileged over those between men and woman, so Queen Telephassa leaves her husband to join the search for Europa, and Ariadne chooses to stay on Crete with her father, because "he is old, and has nobody but myself to love him!".

The use of Roman names – Ceres, Proserpine, Ulysses – is a sign of the influence of Latin sources on Hawthorne. Charles Anthon’s Classical Dictionary, first published in 1825, is believed to have been a key resource. In turn, Hawthorne’s retellings have had a significant influence on more recent retellings, particularly in the continued popularity of memorable, evocative details like Theseus lifting the rock to retrieve his father’s sword and sandals, Jason losing one of his sandals while crossing the river with Hera on his back, and Cadmus throwing the stone amongst the dragon warriors. The charming quality of Hawthorne’s storytelling, underpinned by moments of moralising, combine to render Tanglewood Tales a classic work of the mid nineteenth century. While no longer widely read today, Hawthorne’s retellings play a key role in the continuing tradition of disseminating classical myth to children.

Further Reading

Murnaghan, Sheila, "‘Classics for the Cool Kids: Popular and Unpopular Versions of Antiquity for Children", Classical World 104.3 (2011): 339–353.

Murnaghan, Sheila and Roberts, Deborah H., Childhood and the Classics: Britain and America 1850–1965, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.