Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

J. K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. London: Bloomsbury, 1999, 317 pp.

ISBN

Awards

1999 – Booklist Editor’s Choice Award;

1999 – Bram Stoker Award for Best Work for Young Readers;

1999 – FCGB Children’s Book Award;

1999 – Whitbread Book of the Year for Children’s Books;

2000 – Locus Award for Best Fantasy Novel.

Source: en.wikipedia.org (accessed: January 25, 2021).

Genre

Fantasy fiction

School story*

Target Audience

Crossover

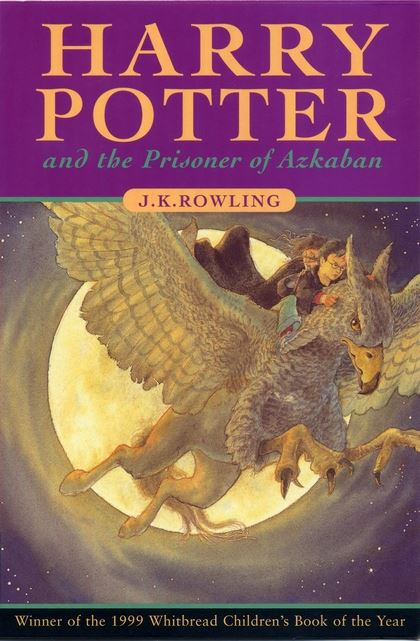

Cover

Cover of the first edition. Courtesy of Bloomsbury Publishing.

Author of the Entry:

Anna Mik, University of Warsaw, anna.m.mik@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Susan Deacy, University of Warsaw, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Portrait of J. K. Rowling, photographed by Daniel Ogren on April 5, 2010. The file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike (accessed: May 25, 2018).

J. K. Rowling

, b. 1965

(Author, Illustrator)

Joanne Kathleen Rowling, was born July 31, 1965 in Yate, Gloucestershire, England. She graduated from the University of Exeter with a degree in French and Classics, she is considered a writer with classical background. After publishing the first Harry Potter book in 1997, she gradually became the best known author of all time.

The Harry Potter septology (1997–2007), is one of the most successful and popular series in the history of children’s literature (Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone sold in 107 million copies). It may be argued that, from the very beginning, the author herself had to expand this world, fill the gaps, and explain all the rules– not only by discussing some issues (later on – mainly on Twitter) or giving guidelines in the interviews but by creating her website Pottermore. Once it was an online platform, where fans could read the series simultaneously with Rowling’s commentary and additions. Now it serves more as commercial space, although Rowling still adds some new elements (e. g. the short history of magical schools in USA).

To give to the devoted fans of Harry something that would allow them to feel the magical bond with the world they want to be a part of she created three books that now exist in both the secondary world of Hogwarts and the primary world where the reader can have a copy in their own hands.

HP Series Spin-offs:

Quidditch Through the Ages by Kennilworthy Whisp (2001), Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them by Newton Scamander (2001) and The Tales of Beedle the Bard (2007)* are allegedly copies of books from the world of Harry Potter which include different literary genres and publication formats: history of sport, bestiaries, and collections of fairy tales. These books are not part of the septology, but they provide complementary information about sports, animals and animal-like creatures, and fairy-tales of the Wizarding World. Additionally, they can be interpreted as a device to help convince readers of the reality of the magical world. In these three books, as in the series sensu stricto, J. K. Rowling plays on various levels with great literary traditions, using one of the many features of postmodern literature.

Bio prepared by Anna Mik, University of Warsaw, anna.m.mik@gmail.com

* Hand-written copies were released in 2007, printed ones in 2008.

Adaptations

Movie adaptation: Alfonso Cuarón, dir., Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, Warner Bros. Pictures, 2004.

Video game adaptation based on the novel and the movie: Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, published by Electronic Arts, composer: Jeremy Soule, 2004.

Translation

Multiple languages

Sequels, Prequels and Spin-offs

Previous volume: Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, 1998.

The following volume: Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, 2000.

Summary

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban is the third book in J.K. Rowling’s series. As every summer, Harry Potter stays with his cousins, the Dursleys, struggling with life in the Muggle world. When the summer is almost over, and he is about to come back to Hogwarts (the school where he learns magic), Aunt Marge, an embittered sister of Vernon Dursley (Harry’s uncle and guardian) comes to visit. She pushes the young wizard’s boundaries to the point when Harry lets go and uses magic to make the woman float in the air like a balloon. Convinced that his magic career is over (underage wizards are not allowed to do magic outside the school), Harry escapes from the Dursleys.

He has not get too far, when his first adventure catches up with him. In the bushes nearby, Harry sees a big black dog staring back at him with a deadly look. Later on, he will find out that the animal (a Grim) is a bad omen in the wizarding community. Scared of the creature, the young wizard pulls out his wand and accidentally summons a magical transport, the Knight Bus. Harry arrives at the Leaky Cauldron (a magical pub in London) hoping to find out what is about to happen because of his insubordination.

In the pub, Cornelius Fudge, the Minister of Magic, assures Harry that what he has done was nothing more than a stupid mistake. What is most important now is that he should remain in a safe space until his return to Hogwarts. As it turns out, there is a dangerous wizard on the loose, Sirius Black, an alleged supporter of Lord Voldemort (the series’ main villain). Little does Harry know that for various reasons the fugitive from Azkaban (wizards’ prison) is particularly interested in him. For a long time, Harry is not aware of the danger, as he meets other difficulties on his way. He goes back to Hogwarts to study magic and reunite with his friends. And of course, fight the evil forces of the wizarding world.

As all other Harry Potter books, The Prisoner of Azkaban is rich in various motifs. Here, I only mention those essential in the context of reception studies.

One of these would be dementors, sinister creatures, guards at Azkaban. They suck out the happiness from people around them and ultimately suck out their souls (which is considered a fate worse than death). They patrol Hogwarts’s surroundings, looking for Sirius Black. Dementors have a particular impact on Harry because he lived through a lot of sorrow and pain (Voldemort killed his parents). He learns to fight them with the patronus charm (“Expecto patronum!”), triggered not only by the incantation but also by happy memories.

Another opponent Harry has to face is a werewolf. Professor Lupin, the new Defence Against the Dark Arts teacher, proves to be the best educator, Harry’s friend, a former friend of his parents and… a werewolf. When Lupin turns, his werewolf nature dominates his human awareness. At some point in the story, he chases Harry and Hermione (one of the boy’s closest friends). Even though he ends up not hurting anybody, Lupin resigns from the job in Hogwarts, conscious of the stereotype about werewolves wide-spread in the wizarding community. Ostracized by the magical society, he has to leave the school.

The Prisoner of Azkaban is a multifaceted story. In this book, Harry finds Sirius, the closest substitute for his family, and almost immediately, is separated from him again. Nonetheless, the wizard learns that he is not alone anymore and has someone to turn to in his darkest hour.

Analysis

As in every other part of the cycle, in The Prisoner of Azkaban classical motifs and tropes abound. The Latinate names or spells, like “Expecto patronum!” (“I await my protector!”) often lead to practise the essential thing in Rowling’s world – magic. Rowling also explores various myths and folktales to create her wizarding reality. Some of them might be associated with classical mythology, but not exclusively so.

The motif of the werewolf and lycanthropy might be one such topic. Even if associated with other cultures and traditions, it might be considered a reinterpretation of the Lycaon myth. The ancient character was turned into a wolf by Zeus as a punishment. Lycaon, the king of Arcadia, killed one of his 50 sons, Nyctimus, and sacrificed him at the altar for Zeus, to check whether the god was all-knowing. The the king’s hubris and his unbelief were punished. What is more, Zeus killed Lycaon’s children, except for Nyctimus, who was resurrected by the god (Apollodorus, Library, 3. 13, 14).

Another ancient character who shared a similar fate was Damarchus, an Olympic boxer from Parrhasia, who won the competition in the 5th century BC (Apollodorus, Library, 3.8). While celebrating the victory during the festival of Lycaea, in the city founded by one of Lycaon’s sons, he consumed the flesh of a boy, who was a human sacrifice to Zeus. In punishment, Damarchus was turned into a wolf, for ten years, or, according to other sources, forever. He could regain human form if he avoided tasting again human flesh.

Even though one might not see a connection between these characters and Lupin, bringing up the concept of punishment may begin to explain the attitude of the wizarding community towards werewolves in the Harry Potter series: they must have done somethings reprehensible, to have been so cruelly punished. Still, Lupin did nothing wrong, and his fate could not be considered his fault. In this way, the author wanted to show the werewolf as a misunderstood creature, unjustly ostracised and excluded by the society. Probably, Rowling borrowed the werewolf image from other myths and traditions. In Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (2009), a handbook on magical creatures of the magical world, she says that werewolves “originated in northern Europe” (p. 83). Hence, there is no direct classical inspiration here.

The dementors, similarly to the werewolves, are not creatures inspired by Greek mythology, they may only be interpreted in the contexts of classical reception. Even if dementors could not be traced to a specific mythological figure, we can compare them at least to a few mythical characters connected to death. One such figure is Thanatos, the god of death. Even though he does not appear often in myths, he is associated with feelings of dread, like dementors who generate despair. They can be interpreted as a methaphor for hopeless finality which accompanies Thanatos’ arrival. Nonetheless, it must be stressed that dementors are evil and merciless. Thanatos, on the other hand is a spirit of nonviolent death, a twin brother of Hypnos (Sleep), he is pitiless but not cruel (Hesiod, Theog. 758–765; theoi.com, accessed: January 25, 2021).

The theme of death appears to be the central issue of The Prisoner of Azkaban not only because of dementors but, also, because of the Grim, the black dog, an omen of death, who in the end turns into a figure of hope. Falsely accused, Sirius Black (for the name analysis, see Spencer, 2016, p. 113)* turns out to be the dog seen by Harry at the beginning of the book and his god-father. Since antiquity, the brightest star at the sky was called “Sirius,” or “the Dog Star”, which derives from the myth of Orion and his hunting both turned into constellations (p. 113). As Spencer also notes: “[…] just as the star Sirius shines with unique brightness in the dark heavens, Sirius Black outshines many other characters in the Harry Potter series by his notoriety” (p. 113). He is faithful, determined to protect his friends at all costs, and ready to sacrifice himself for Harry. Than, the Dog analogy is more than accurate.

It is possibly the first “truly dark” book of the series; as the characters are adolescents now, the story abandons its “fairy-tale” character and acquires features of horror or dark fantasy. Nonetheless, Rowling does not leave her readers with no hope. The patronus charm (spell relying on good memories and happiness) repels dementors, and the alleged Grim turns out to be one of the closest people to Harry. Maybe, after all, the death might be befriended, even if it seems very scary (more on death in Harry Potter see Mik, 2018)**.

* Richard A. Spencer, Harry Potter and the Classical World: Greek and Roman Allusions in J.K. Rowling’s Modern Epic, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2016.

** Anna Mik, “Śmierć bedzie ostatnim wrogiem, który zostanie zniszczony”. Dziecko-horkruks w cyklu o Harrym Potterze J. K. Rowling [“The last enemy that shall be destroyed is death”: The Child-Horcrux in Harry Potter Series by J.K. Rowling], in Katarzyna Slany, ed., Śmierć w literaturze dla dzieci i młodzieży [Death in Literature for Children and Young Adults], Warsaw: Stowarzyszenie Bibliotekarzy Polskich, 2018.

Further Reading

Mik, Anna, “Śmierć bedzie ostatnim wrogiem, który zostanie zniszczony”. Dziecko-horkruks w cyklu o Harrym Potterze J. K. Rowling [“The last enemy that shall be destroyed is death”: The Child-Horcrux in Harry Potter Series by J.K. Rowling], in Katarzyna Slany, ed., Śmierć w literaturze dla dzieci i młodzieży [Death in Literature for Children and Young Adults], Warsaw: Stowarzyszenie Bibliotekarzy Polskich, 2018.

Olechowska, Elżbieta, “J.K. Rowling Exposes the World to Classical Antiquity” in Our Mythical Childhood… The Classics and Literature for Children and Young Adults, Katarzyna Marciniak, ed., Leiden: Brill, 2016, 384–410.

Rowling, J. K., Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, London: Bloomsbury, 2009.

Spencer, Richard A., Harry Potter and the Classical World: Greek and Roman Allusions in J.K. Rowling’s Modern Epic, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2016.

Whited, Lana A., ed., The Ivory Tower and Harry Potter: Perspectives on a Literary Phenomenon, Columbia and London: University of Missouri Press, 2002.