Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

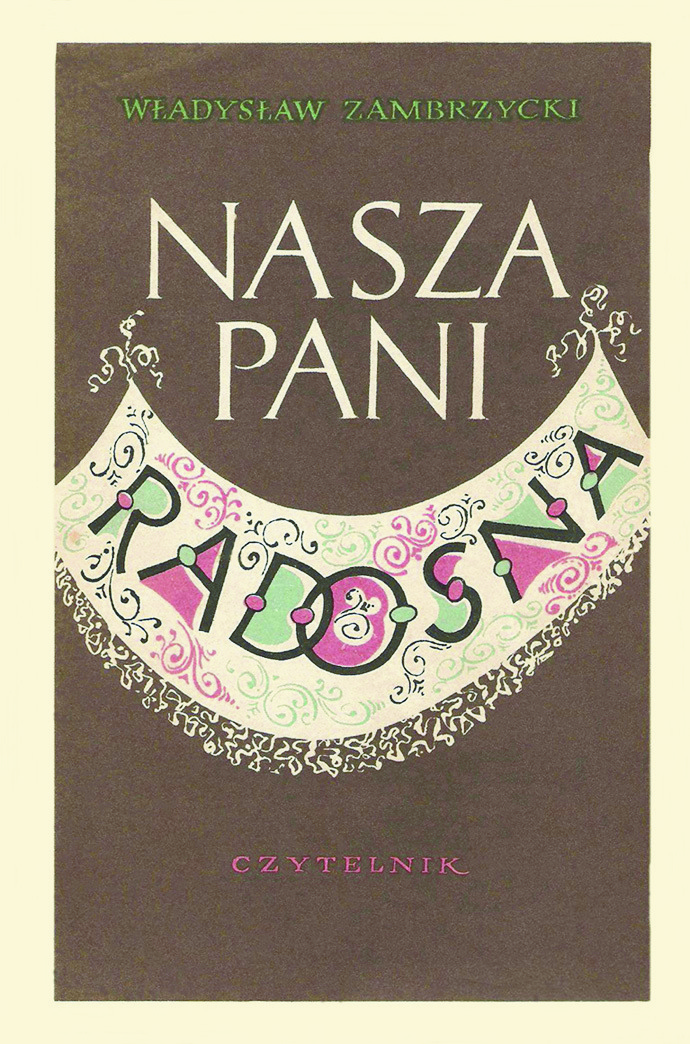

Zambrzycki, Władysław, Nasza Pani Radosna, czyli dziwne przygody pułkownika armii belgijskiej Gastona Bodineau. Warszawa: Rój, 1931, 324 pp.

ISBN

Available Onllne

Nasza Pani Radosna (accessed: April 30, 2021).

Genre

Time-travel fiction

Target Audience

Crossover (teenagers, young adults)

Cover

Scan of the cover kindly provided by Maria Pajzderska.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Daria Pszenna, University of Warsaw, dariapszenna@student.uw.edu.pl

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Photograph courtesy of Maria Pajzderska, the Author’s Niece.

Władysław Zambrzycki

, 1891 - 1962

(Author)

An erudite, a lover of history and literature, author of plays, short stories, historical novels. Born in Radom, attended university (chemistry) in Belgium. After an escape from Russia and the Bolshevik Revolution, he settled in Warsaw. He considered himself above all a journalist. He was fond of saying that he had journalism in his blood, but when feeling the need for fantasy, he wrote novels. Contributed to Polish magazines, such as “Express Poranny,” “Nowiny Codzienne,” “Tygodnik Ilustrowany,” “Merkuriusz Polski Ordynaryjny,” and “Nowe Wiadomości Ekonomiczne i Uczone.” Zambrzycki also had a weekly column in “Ekspres Wieczorny” – a Polish evening newspaper published in Warsaw. One of his most popular books is Kwatera Bożych Pomyleńców [Quarters of God’s Fools], 1959, produced in 2009 as a play by Teatr Telewizji (a department of Polish Public Television) directed by Jerzy Zalewski. The novel tells the story of four elderly gentlemen having a discussion in a library during the Warsaw Uprising (1944). Zambrzycki also wrote three plays at the end of WW2; they were never published, or staged.

Source:

Władysław Zambrzycki. Życie i twórczość, [Website dedicated to the Author] (accessed: May 9, 2022).

Bio prepared by: Daria Pszenna, University of Warsaw, dariapszenna@student.uw.edu.pl

Translation

Hungarian: A mi boldogasszonyunk avagy Gaston Bodineau belga, trans. István Mészáros, Budapest: Európa Könyvkiadó, 1959.

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

The book is written in the form of fictitious memoirs of the author, who in this time-travel story along with Colonel Bodineau and two other friends – Jeff van Campen and Kuba Schroetter – moves to Pompeii of the 1st century AD. They decide to settle there and open their own distillery. This is a great opportunity to observe ordinary lives of the citizens of Roman Italy. From this story you can learn a lot about meals, entertainment, administration of the country, the army, and even about how the ancients treated rheumatism. The characters do not limit themselves to observing the ancient Romans and Greeks. They bring to this world modern culture and civilization creating a clash which is the source of humour and reflection. The story also treats serious topics, such as religious issues (Judaism, paganism, cult of the Persian god Mithra). In a curious twist of events, the characters bring back to their own times a wise priest of Juno and a statue of the goddess. The priest becomes a Catholic and the statue is viewed as an effigy of the Virgin Mary. This is presented as the origin of the cult of Notre Dame de Liesse.

Analysis

This novel combines two realities: the 20th century, shortly after the Great War, and Campania Romana, just before the deadly eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. This clash and mixture of the two worlds and cultures is a source of comedy and entertainment. The protagonists escape from their own time chased by law enforcement agencies from several countries. They do not use their 20th-century knowledge to change the past on purpose, conduct historical research, or adjust better to the ancient culture, but rather to make money. They become well-off entrepreneurs owing to the technology of producing twice distilled alcohol, i.e. vodka, manufacturing playing cards, and winning Olympic laurels by translating modern poetry. They have a significant impact on Pompeian society. They distribute their products, along with elements of the 20th-century culture and lifestyle, to a wide public (introducing hard liquor, card games, football matches, the women’s hairstyle trend à la garçonne, and poetry of Kazimierz Wierzyński – a Polish poet living in 1894–1969). All these elements, unknown in Roman times, impact not only the private lives of particular people – for instance, an aedile, under the influence of alcohol, quarrels with his wife and mother-in-law, throws off the women’s rule, regains his manly pride and social position, thus becoming the best advertisement of the power of aqua vitae. The entire society is impacted as well; for example, the distribution of hard liquor during games in the Pompeian amphitheater leads to hooligan fights with the Nucerians, eventually causing the emperor Vespasian to prohibit all games.

Although the “alcoholic” subplot seems inappropriate for children, besides highlighting the negative consequences of using and abusing alcohol, the novel’s educational value is undeniable. The author uses the convention of an action novel but does not limit his focus to the protagonist’s adventures. The background he presents is extensive, diverse, well researched and refers to many aspects of life in the meridional region of the Roman state in the 1st century AD.

The protagonists can speak a Modern Greek dialect they previously learnt in Thessalonica and do not know any Latin, so they use Greek to communicate. This device introduces the Greek language as a lingua franca and informs the reader of the Greek-speaking majority in Campania; this included Jews from Jerusalem and Alexandria, Romans, Greeks, Osci, local countrymen and slave servants. It shows the deep Greekness of former Magna Graecia and its communities so that even Romans who are there adjust to this and treat speaking Greek as a necessity and an attractive hobby, all at once.

The protagonists explore a vast range of ancient territory: Aenaria, Herculaneum, Naples, Paestum/Poseidonia, Pompeii, Puteoli, Stabiae, Surrentum, and Olympia. Pompeii plays a key role and thus is described in more detail. The author presents various places, activities, cultural events and people, including their origin and status; everything firmly based on historical and archaeological research. The reader can “visit” with the protagonists the Pompeian forum, the thermae, two theatres, an amphitheatre, a gladiators’ casern, a cemetery, shops, taverns, hostelries, private dwellings including Jewish houses, a kosher restaurant, and such places as a morays’ farm and a sanatorium/health spa organized by Asclepius’ priests on Aenaria (today: Ischia). The sights chosen by the author are not just ornamental but are also teeming with life: Zambrzycki introduces many cultural customs, usages, everyday practices and institutional activities in which the protagonists engage. To enrich the depiction of the ancient reality, the author presented meals, garments, hair fashion, music, cleansing rituals, massages in the thermae, the custom of gifting honey for the New Year, Liberalia – a festival with a comedy, OI BAPBAPOI, inspired by the newcomers, purchases of love potions from a herbalist, sposalia – a kind of engagement ceremony, engyesis – another kind of engagement, nuptials, labour, a slave auction, and arms and military manoeuvers. There is even graffiti on the wall of a tavern’s toilet and measuring time spent in a steam bath by declamation of the Aeneid.

Social issues commonly connected with cruelty and mistreatment, like slavery or gladiators’ games, are introduced by the author in a lighthearted manner without emphasis. A Greek slave harpist, Helen, could buy her freedom using accumulated peculium savings, but she does not want to be freed because she likes her master and feels at home in his family. When she falls head over heels in love with Kuba, he, a free man, has to flee to escape her insistent advances. On a street of Pompeii, another slave woman argues with her master that he should buy her a coat; she claims it is due to her because of the high price she could fetch on the slave market and the number of potential buyers. The master seems to be visibly more modest than his slave. Another slave is a lazy loafer causing trouble to his owner. She would like to sell him, but is worried he would feel uncomfortable being sold below his value; she seemingly cannot force him to work. When Vespasian considers a Polish protagonist from Calisia to be a foe of the Empire and orders him to be sold into slavery, the latter reaches such a stunning price that despite becoming a slave, he is still treated with reverence and esteem. Gladiators and their fights are described similarly: death or injuries are not mentioned. On the contrary, the protagonists learn that nobody dies – training and tuition are so expensive that owners do not want to risk losing a gladiator; the result of the fights is predetermined. The precious participants are not harmed. To avoid any harm to the gladiators from wild beasts, these animals are first starved and, a short time before the games, are well-fed and therefore lazy and as meek as lambs. The issue of rape is approached in a similar manner, calming any sensitive readers. A widow, the host of the protagonists, is kidnapped by rogues from Vesuvius’ area, and there is no news about her. Eventually, she returns in surprisingly good condition and says that she was kept captive by a dozen rascals. The word rape is not mentioned explicitly, but it is evident that she was a victim of sexual abuse, having been forced “to serve” them one after another, becoming pregnant as a result. Her case is presented with humour as if it were a kind of blessing for her and the only chance to have the baby she desired. Uncertainty of the father, whose name should be recorded by the aedile, is again described with a dose of humour. The clever aedile finally calls the newborn Lucius of Vesuvius.

The only harsh scenes are related to the massacre of the Herculanean Jews, committed by the legionnaires, and the catastrophic last hours of Pompei. The Jewish community is presented as somewhat similar to communities in Poland, as they were in the 1920s or 1930s. It is divided into two factions according to the origin of their members (Jerusalem and Alexandria). The rabbis of the two groups constantly clash on their philosophical differences, Scriptures and their interpretation. The Jewish society observes its own laws and traditions, makes sacrifices differently than Romans, eats differently and differently ornaments their houses. The author’s attitude, manifested in his use of stereotyped dialogues in Izhak’s house, resembling small talk of Jewish “hustlers” from Warsaw between the two world wars, reflects a historical sense of humour.

Last but not least, the presence of historical characters should be noticed – Plinius the Elder is quite properly called admiral as he actually commanded the fleet in Misenum. He makes linguistic corrections of poetry for van Campen. He believes the Belgian wrote the poems himself and encourages him to participate in the Olympic contest for poets. In fact, it is a translation of Wierzyński’s poems. When van Campen wins the wreath, the true winner is Wierzyński, awarded the gold medal for poetry at the Games of the 9th Olympiad in Amsterdam in 1928.

Further Reading

Wojciechowski, Michał, "Nasza Pani Radosna", Najwyższy Czas! 39 (1994): 6 (accessed: February 8, 2013).