Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Sandra Lawrence, Myths and Legends. London: 360 Degrees (an imprint of Little Tiger Group), 2017, 63 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Myths

Picture books

Target Audience

Children (aged c7+)

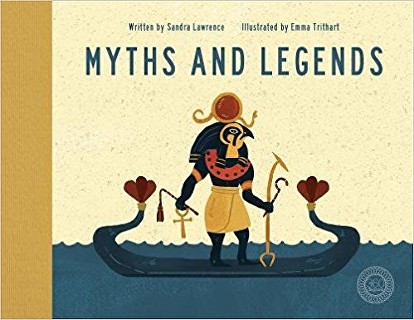

Cover

Courtesy of Catepillar Books, publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Sonya Nevin, University of Roehampton, sonya.nevin@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Dorota Mackenzie, University of Warsaw, dorota.mackenzie@gmail.com

Sandra Lawrence (Author)

Sandra Lawrence is a British journalist and writer. She began as a singer, moved into featured journalism and now combines journalism with writing books, particularly non-fiction children's books. Sandra Lawrence developed the Grisly History series (Weldon Owen Books 2016; published by Little Bee Books as Hideous History in the USA). She has written Festivals and Celebrations and Myths and Legends for 360 Degrees (360 Degrees, 2017). She published Atlas of Monsters (Big Picture Press, 2017) and 2018 will see the publication of the Anthology of Amazing Women: Trailblazers Who Dared to Be Different (forthcoming 2018).

Source:

Official website (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Bio prepared by Sonya Nevin, University of Roehampton, sonya.nevin@roehampton.ac.uk

Emma Trithart (Illustrator)

Emma Trithart is an illustrator, hand letterer and graphic designer based in Los Angeles, USA. She trained at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design.

Bio prepared by Sonya Nevin, University of Roehampton, sonya.nevin@roehampton.ac.uk

Summary

Sandra Lawrence's Myths and Legends is relatively unusual amongst children's myth books in that it places more emphasis on comparative mythology than on story-telling. The book's five sections are arranged to stress features shared in common across myths, such as journeys, creation, trees, tricksters, and solar chariots. Some myths are told in summary form to demonstrate the story types that are being introduced (King Arthur: The Once and Future King and Theseus: The Highly-Strung Hero for heroism; Good Triumphs over Evil: Hooray! for bad characters; Seasonal Tales for aetiology and stories about the natural world; Jason and the Golden Fleece for journeys; Love Blossoms and Love's Light for love stories.).

Table of Contents:

Section One. Gods and Heroes

- Good gods.

- Holy Technology!

- We Could be Heroes

- Heracles: When the Going Gets Tough

- King Arthur: The Once and Future King

- Theseus: The Highly-Strung Hero

- Tricksters: Now you see them

- Mwahahaha...It's the Bad Guys

- Nasty Mythical Beasts

- Good Triumphs over Evil: Hooray!

- Mini Stories: Gods and Heroes

Section Two. Creation Myths

- 'In the Beginning'

- It's a God-Eat-God World

- The Tree of Life

- Mini Stories: More Beginnings

Section Three. Mythology and the Natural World

- Solar Flair

- Seasonal Tales

- Thunder and Lightening

- A Dazzling Natural Lightshow

- Other Natural Phenomena

Section 4. Mythical Journeys

- Jason and the Golden Fleece

- Quest for the Holy Grail

- The Seven Stories of Sinbad

- Pandora's Box: Be Careful What You Open

- Mythical Realms

- Mini Stories: Mythical Journeys

Section 5. Legendary Love Stories

- Love Blossoms

- Love's Light

Analysis

The book's introduction welcomes the reader to 'the wonderful world of myths and legends', offering 'tales from different societies and cultures'. Myth is accounted for in two ways: as stories so old that people are unable to recall if they are true or not, and as stories used to explain the incomprehensible aspects of the life and the universe. The first of these perspectives is influenced by the rather discredited historicising approach to myth, which held that myths were essentially records of real events that got more fantastic over time. Mythologists may find it unfortunate that the book opens with this approach, however it holds little place within the rest of the book and the true/false dichotomy does not reappear. It seems likely that there is a pro-multi-culturalism ideology behind the collection, as the emphasis falls on what is similar between traditions rather than on areas of difference or what the differences might indicate, and the purpose of drawing out similarities appears to be to foster broad cultural knowledge and a sense of shared traditions. Taken to an extreme, over-emphasis on similarities and under-emphasis on difference can lead to colonialist representations of myth and religion by sublimating meaningful difference within an externally imposed framework; in an introductory text like this, the reader is more simply equipped to recognise key myths and tropes from twenty-four different cultures and encouraged to be alive to tropes and patterns.

The twenty-four cultures included are:

African (Kuba), African (South Africa), Afro-Caribbean, Australian, Aztec, British, Cree, Egyptian, Estonian, Finnish, German, Greek, Hawaiian, Hindu, Hungarian, Irish, Japanese, Middle Eastern, New Zealand, Norse, Roman, Russian, Scottish, South American.

If each culture was represented equally across the sixty-five traditions included, each would have two to three entries each. A different approach has been taken, with ancient Greek myth accounting for fourteen of the entries, making it by far the most well represented mythic tradition. Ancient Egypt, via a striking image of Horus, was chosen to promote the book via its cover.

The book begins with an image of a golden palace complex atop Mount Olympus, facing an image of a beardless Heracles smiling and holding his club. The two images form the visual representation of the texts contrast between gods and heroes, with the youthful-looking Heracles providing a friendly face for the latter. Holy Technology describes special objects used by gods, with Zeus and Hermes forming two of the examples. As in much of the rest of the book, the gods are described in the present tense; Zeus 'uses thunder and lightning'. This reinforces the concept of deities' divinity – their immortality – and this mode may also have been adopted in order to show respect for the mythologies that retain practicing adherents. Heroes are described and myths narrated in the past tense. Combined, this creates the sense that heroes lived a long time ago, that myths took place a long time ago, while gods persist into the present age. This is a relatively unusual way to refer to Greco-Roman gods and the effect is to add a degree of dynamism to their representation.

Heracles' Labours feature as an example of heroism. The labours are described in a list format. They are explained as 'almost impossible' deeds that Heracles accomplished which made him a 'legend', without getting into the detail of why the labours took place, presumably to avoid potentially disturbing themes and the ambiguity that arises from discussing heroes doing wrong. This trend continues in Theseus: The Highly-Strung Hero. A traditional retelling of the labyrinth myth is narrated, finishing by noting explicitly that Theseus 'kept his word and took Princess Ariadne away with him.' While traditions for this myth agree that Theseus took Ariadne off Crete, most follow this with him abandoning her on Naxos (see e.g. Diodorus of Sicily, Library, book 4; Plutarch, Theseus; Apollodorus, Library, book 3; Ovid, Metamorphoses, 8.155-182; Apollodorus, Epitome, 1.7-11 forms an unusual contrast in which Theseus is unwillingly separated from Ariadne). The emphasis on Theseus keeping his word therefore reflects a decision to obfuscate the traditions of his betrayal, presumably in an attempt to depict heroes as unambiguously moral. The myth of the Chimera emphasises Athena helping Bellerophon. Rather unusually, the gift of Pegasus is said to enable Bellerophon to attack two heads at once; more typically within children's literature, the story ends with Bellerophon's attack rather than his punishment for arrogance. This makes sense in context, as the section is Nasty Mythological Beasts, so the focus is Chimera, not Pegasus or Bellerophon himself. Nonetheless, the decision to tell the Chimera-Bellerophon-Pegasus myth from this perspective enables a continued representation of the hero as an unmitigated force for good.

The section on 'bad guys' includes the Gorgon, Medusa (alongside Baba Yaga, Baron Samedi, and the god Set). Medusa is depicted somewhat like a sulky teenager, wearing a cropped top and looking disinterestedly at her nails. If nothing else, this addressed the difficulty of representing the Gorgon's terrible gaze. Medusa's form is taken from the Clash of the Titans (1981) tradition, with a snake tail forming her lower half. The creation chapter includes stories from Norse, Hindu, Native American, ancient Greek, and ancient Egyptian traditions. The Greek double-page briefly recounts the change from Chaos to the age of Gaia, Uranus and the Titans, with more detail on Zeus' wily tricking of Kronos.

In Seasonal Tales, the story of Persephone is retold with explicit notice of its importance as an explanation for the changing seasons. The myth is retold in fairly neutral language: reference to Hades 'kidnapping the beautiful Persephone' implies that he is motivated by her beauty, but does not, as so often in children's literature, make mention of him being in love or being lonely; i.e. no excuse is offered for his actions. Demeter's search for Persephone is described without reference to the effect it had on humans, which avoids the implied criticism which frequently appears in modern narratives of this myth. The non-sexist nature of the text is somewhat contradicted by the image chosen to illustrate the myth. The viewer is placed in the position of someone approaching Persephone from behind, like a stalker, apparently in the role of 'kidnapper' Hades. Persephone looks back coquettishly over her bare shoulder, distracted from picking flowers, smiling at the approaching viewer with her bottom shown in a 'presenting' pose. It is the only sexualised image in the book, which is all the more apparent when one considers that the image eroticises Persephone's kidnap and suggests her complicity. While the narrative provides an example of mythical aetiology for the seasons, the illustration emphasises some of the more problematic elements of the myth and its relationship with patriarchal values.

Jason appears in the section Mythical Journeys. The accompanying image depicts him holding a sword aloft above a sleeping dragon with the Golden Fleece in the background. This retelling of Jason's adventures treats the attempt on the Fleece quite briefly, leaving space for reference to events earlier on in the myth such as the clashing rocks, harpies, and Talos. The Argonauts succeed 'thanks to their courage and ingenuity'. Medea does not appear.

Pandora's Box is subtitled Be Careful What You Open, adding a rare moment of explicit moral guidance. While the sub-title adds a moral caution, the retelling of the myth minimises Pandora's role in a way that is fairly consistent with ancient traditions, in which a chain of events, rather than Pandora herself, are primarily responsible; Pandora's creation is explicitly linked to revenge against Prometheus situating the release of the evils within the framework of punishing all humans. The 'box' is depicted in the manner of the Lilius Giraldus of Ferrara tradition and the 'evils of the world' are shown as moths upon a swirling dark wave.

Mythical Realms refers to how 'Plato famously made up' Atlantis, and that people ended up believing in Atlantis all the same. Legendary Love Stories includes the only explicitly 'Roman' myth – Cupid and Psyche. The brief retelling opens with Venus separating the lovers and their efforts to be reunited. As with the representation of heroes earlier in the book, this presentation of the Cupid and Psyche myth avoids any suggestion of moral failing on the part of the protagonists, preferring to focus on their endeavours.

There is an interesting colour scheme at work in the depiction of Greco-Roman gods and heroes. Heroes are mostly depicted with Mediterranean complexions (Heracles has olive skin, Theseus has a dark complexion and dark hair, only Jason is pale-skinned, he is also brunette). Gods, by contrast, are presented in a more northern European style: Athena, Demeter, Gaea, Hade, Hera and Kronos are pale-skinned brunettes, Zeus is a slightly darker-skinned brunette, Hestia and Persephone are blonde, Hermes blonde and ruddy-cheeked, while Poseidon has white-grey hair. This pattern would suggest that while the heroes are visually situated in a Mediterranean context, the gods are more removed from that context and have been brought closer to a more Norse god look. This different treatment of gods and heroes perhaps reflects the text's distinction between these two groups in the use of past and present.

As promised in the introduction to Myths and Legends, this book welcomes the reader into the wonderful world of myth, and myth appears as a source of varied delights and horrors. It amply demonstrates a shared love of story-telling across human cultures.

Further Reading

Dowden, Ken, The Uses of Greek Mythology, London and New York: Routledge, 1992.

Dowden, Kenneth and Niall Livingstone, eds., A Companion to Greek Mythology, London: Blackwells, 2011.

Hinnels, John, The Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion, London and New York: Routledge (Second Edition) 2010.

Leeming, David A., Myth. A Biography of Belief, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Leeming, David A., The World of Myth. An Anthology, Oxford: Oxford University Press (Second Edition) 2014.