Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

John Connolly. The Book of Lost Things. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 2006, 352 pp.

John Connolly. The Book of Lost Things. New York: Atria Books, 2006, 352 pp.

ISBN

Awards

2007 – nomination for the Irish Novel of the Year prize in Irish Book Awards contest;

2007 – one of the ten books that received Alex Awards, granted by the Young Adult Library Services Association (YALSA), a division of the American Library Association (ALA).

Genre

Fantasy fiction

Fiction

Novels

Portal Fantasy*

Target Audience

Young adults (Note that many readers, reviewers and critics, because of the included images of violence and cruelty, and the presence sexual motifs, perceive the book as an )

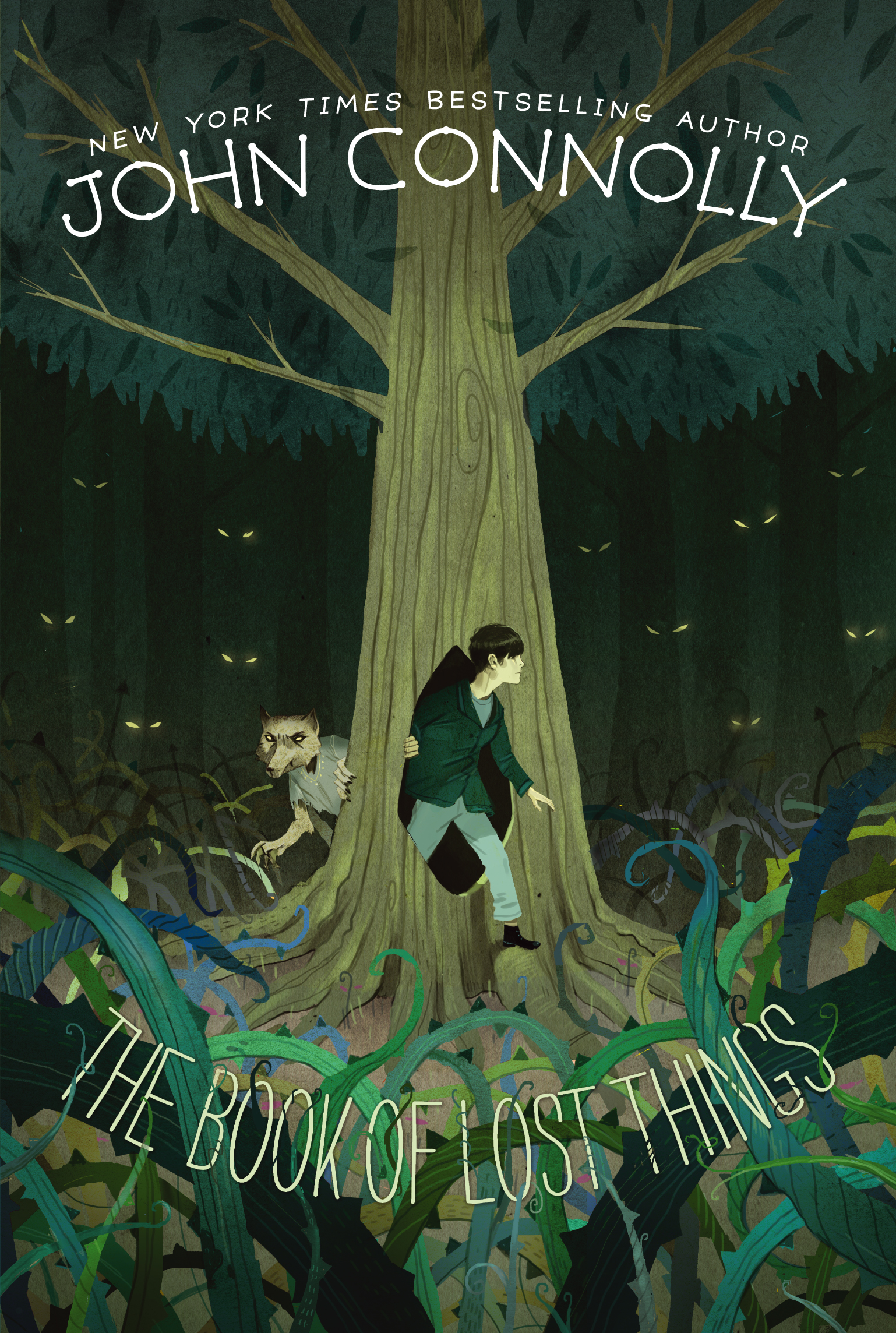

Cover

Courtesy of Simon & Schuster, the publisher (edition from 2011).

Author of the Entry:

Maciej Skowera, University of Warsaw, mgskowera@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

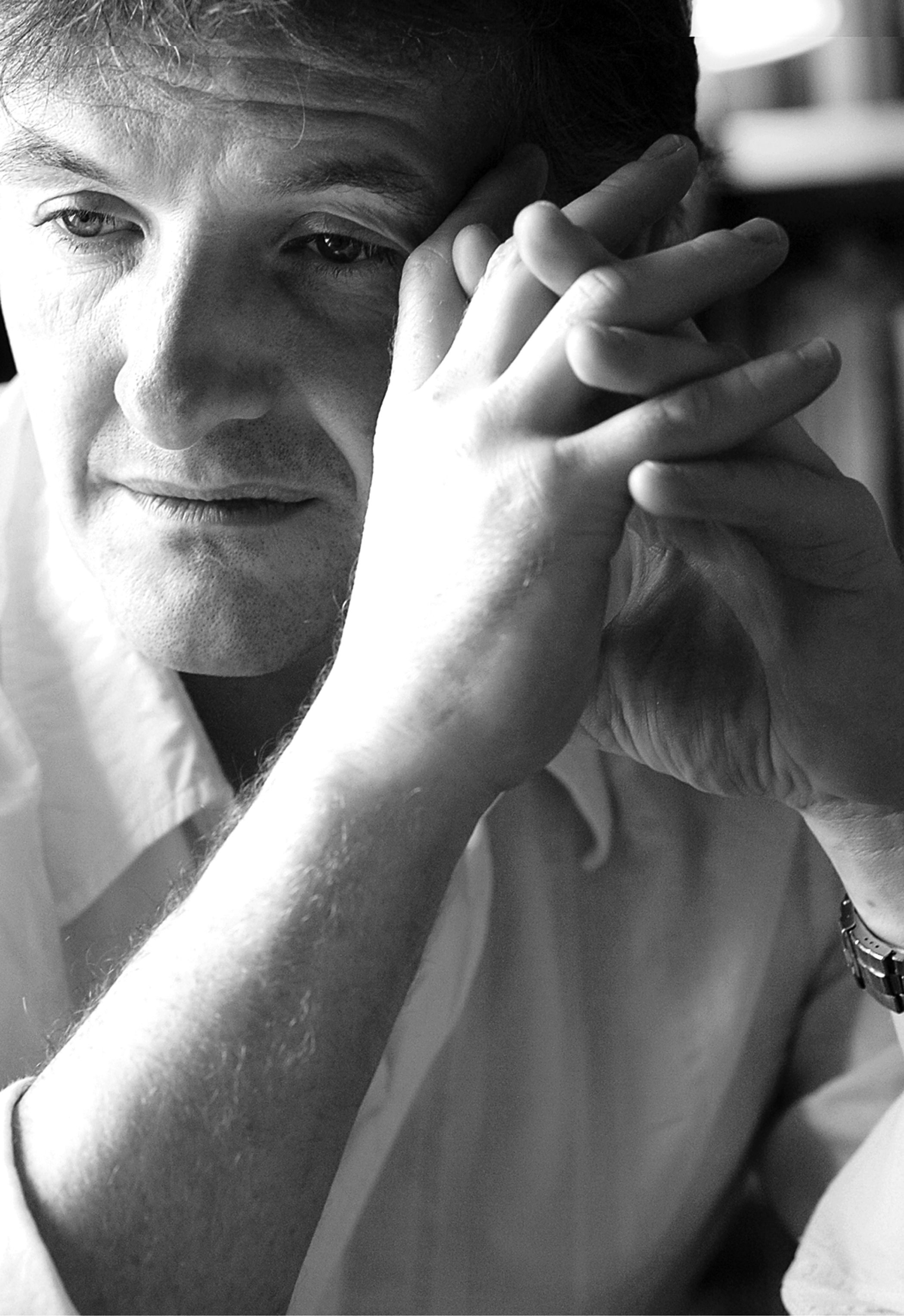

Portrait taken by Ivan Gimenez Costa, courtesy of the Simon & Schuster, publisher.

John Connolly

, b. 1968

(Author)

An Irish writer specialized in crime, horror, and supernatural fiction, he holds a B.A. in English, obtained at Trinity College in Dublin, and an M.A. in journalism from Dublin City University. Before starting his writing career, he worked as a journalist, a bartender, a local government official, a waiter, and – as stated on his official website – “a dogsbody at Harrods department store in London.” He is probably best known for his multivolume supernatural crime series of novels about an anti-heroic former policeman, Charlie Parker (the first book in the cycle, Every Dead Thing, published in 1999; the latest one, The Woman in the Woods, in 2018). He also wrote a fantasy/horror trilogy for younger readers about Samuel Johnson’s adventures (2009–2013), a cycle of young adult fantasy books The Chronicles of the Invaders (2013–2016), co-created with Jennifer Ridyard, as well as standalone novels: Bad Men (2003), The Book of Lost Things (2006), He (2017; a fictional biography of Stan Laurel), and stories and novellas, some of which were published in collections: Nocturnes (2004) and Night Music: Nocturnes Vol. 2 (2015). For his works, he received numerous prizes, such as the “Shamus Award,” the “Barry Award,” the “Agatha Award,” the “Antony Award,” the “Edgar Allan Poe Award,” and the “Alex Award.” He lives between Dublin and Portland, Maine. He is a wine connaisseur and an admirer of dogs.

Sources:

Official website (accessed: July 4, 2018).

About John, available at www.johnconnollybooks.com (accessed: July4, 2018).

Bernard A. Drew, “John Connolly”, in idem, 100 Most Popular Contemporary Mystery Authors: Biographical Sketches and Bibliographies, Santa Barbara, Denver, Oxford: Libraries Unlimited, 86–88.

Bio prepared by Maciej Skowera, University of Warsaw, mgskowera@gmail.com

Translation

The Book of Lost Things was translated into multiple languages.

Summary

The protagonist, twelve-year-old David, lives in London. Shortly before the start of World War II, his mother dies. The boy is charged with taking care of her books: folk and fairy tales or narratives about knights, dragons, etc. He tries to avoid thinking about these stories, but the books do not allow him to do that, as he begins to hear them talking – the more time passes, the louder they become. When David’s father meets his new partner, Rose, the boy starts to faint and to have visions, in which he sees a forest, hears the wolves howling, and meets the Crooked Man, a creature from a nursery rhyme. Davis is sent to a psychiatrist, but it does not resolve the problem.

In December 1939, David learns that Rose is pregnant. At the same time, the situation in London becomes more and more dangerous. After Rose gives birth to a boy named Georgie, all of them move to her family’s old house located in the countryside. While this is meant to protect them from the horror of war, David has to face his own problems: his growing antipathy towards Rose and his younger brother and the increasing complexity of the relationship with his father. Additionally, he still has dreams about the Crooked Man. The boy tries to find entertainment and consolation in books – but most of what he finds in the new home is for “adults,” incomprehensible to him, full of darkness and violence, or odd. He reads historical works on communism and World War I, a textbook of French vocabulary, a book on Roman Empire, Robert Browning’s Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came (1855), and old volumes of forgotten, twisted folk and fairy tales.

One night, David has a vision of his mother, who states that she did not really die, but was imprisoned in a strange realm, and that she needs his help. He believes in it and leaves the house. Outside, the boy sees a shot down German plane, falling into the garden. David quickly squeezes through a hole in the wall, which is a portal to the land from his visions. It turns out that it is a dark and dangerous place, inhabited by terrifying creatures derived from the books that the child read, for example: the descendants of a wolf and a girl who wore a red hood, called the Loups; a morbidly obese equivalent of Snow White, who oppresses communist-like dwarfs; repulsive harpies; a murderous monster resembling Sleeping Beauty.

The Crooked Man is a particularly terrifying figure. He tricks children who feel jealousy and anger towards their siblings to reveal their names to him. Thanks to this, he gains power over all of them. The betrayers become figureheads who rule the kingdom ineptly, being fully under his control. The souls of the victims of these betrayals are locked in jars by the Crooked Man, so he can use their life energy and prolong his own life, which is filled with wickedness. As the rule of the current king is probably coming to its end, the Crooked Man wants David to reveal his younger brother’s name to him, promising can live again the life he had when his mother was alive.

The protagonist, with the help of the Woodsman and the knight named Roland, wanders through the dark kingdom. He seeks his mother, but also the king. The sham ruler owns the title Book of Lost Things, which is supposed to help the boy to come back home. In the course of the plot, it becomes clear that the boy’s mother is dead, so his previous life cannot be restored, and that the Crooked Man is lying. When David eventually enters the king’s castle, it is revealed that the King is Jonathan Tulvey, Rose’s uncle who disappeared years ago along with his adopted sister – betrayed by him in a result of the antagonist’s persuasion. The novel’s main character, however, refuses to betray his brother. Therefore, when Leroi, one of the Loups, kills the king, the Crooked Man’s life ends.

David, accompanied by the Woodsman, comes back to the forest where he arrived after crossing the border separating the two worlds. They find a portal and the boy leaves the kingdom. He wakes up in a hospital and apologizes to Rose. The last passages of the novel shortly summarize the protagonist’s life until he dies, including such events as the divorce of his stepmother and father, Georgie’s death in the war, and the deaths of David’s wife and son. He becomes a writer and creates a work under the same title as Connolly’s novel: The Book of Lost Things. Finally, when David is an old man, he once again finds the passage to the fantasy land, where he is reunited with his wife, Alyson, and their son, George.

Analysis

Weronika Kostecka indicates that the dark and dangerous land from Connolly’s novel is inhabited by, inter alia, “[…] figures from the Grimms’ tales; the boy identifies subsequent fairy-tale-derived elements (characters, events, sceneries) and, at the same time, to his horror, he discovers that they have been transformed thanks to the power of someone’s cruel imagination […].”* However, in the fantasy kingdom, David also meets beings and hears about people who have their roots in classical antiquity.

As this secondary world is largely based on the books the protagonist read, it should be stressed that, after moving to Rose’s family’s house, he found “[…] a book about the Roman Empire that had some very interesting drawings in it and seemed to take a lot of pleasure in describing the cruel things that the Romans did to people and that other people did to the Romans in return.”** Later, we read that one of the Crooked Man’s former victims was Manius. He was very greedy and possessed a large area of land. He made a deal with the demonic creature that he would sell his land for gold weighing as much as he would eat during a banquet. “That night, the Crooked Man sat and watched as Manius ate and ate. He consumed two whole turkeys and a full ham, bowl upon bowl of potatoes and vegetables, whole tureens of soup, great plates of fruits and cakes and cream, and glass after glass of the finest wines. The Crooked Man carefully weighed it all before the meal began, and weighed the meager remains when the meal was over. The difference amounted to many, many pounds, or enough gold to purchase a thousand fields.”*** The Crooked Man kept his word: he filled Manius’ stomach with molten gold, which “[…] poured down his throat, scalding his flesh and burning his bones,”**** and resulting in his long and extremely painful death. This story is basing on the fate of Manius Aquillius, a Roman ambassador to Asia Minor, who in 88 BC was executed by King Mithridates VI of Pontus by having molten gold poured down his throat. Therefore, the images of horror and cruelty that appear in Connolly’s novel are not inspired only by folk and fairy tales, but also by ancient history.

What is more, David has his own collection of Greek myths. The stories he read come to life when the boy, accompanied by the Woodsman, encounters the harpies of the Brood. These creatures, cowardly but extremely hungry, live near a great chasm, where they wait to kill and eat everything that falls there – as they themselves state: “What falls is food,/ What drops will die,/ Where lives the Brood,/ Birds fear to fly.”***** Their enemies are the trolls, who hunt the harpies using harpoons. The protagonist and his companion try to avoid both types of creatures, but it turns out that they must solve the trolls’ riddle and choose one of the two bridges over the chasm – stepping on the wrong one means a deadly encounter with the harpies or the trolls.

The image of the harpies is particularly interesting here. In the novel, we read that the boy “[…] saw a shape, much larger than any bird that he had ever seen, gliding through the air, supported by the updrafts from the canyon. It had bare, almost human legs, although its toes were strangely elongated and curved like an eagle’s talons. Its arms were outstretched, and from them hung the great folds of skin that served as its wings. […] David glimpsed its naked body. He looked away immediately, ashamed and embarrassed. It had a female form: old, and with scales instead of skin, yet still female for all that. […] David had an opportunity to examine its face as it hovered: it resembled a woman’s but was longer and thinner, with a lipless mouth that left its sharp teeth permanently exposed. Now those teeth tore into its prey, ripping great chunks of bloody fur from its body as it fed.”******

It is therefore visible that the harpies of the Brood have little in common with Hesiod’s “fair-tressed Harpies, Aello and Okypete,”******* but are undoubtedly based on another tradition: “[…] even as early as the time of Aeschylus (Eum. 50), they [the Harpies] are described as ugly creatures with wings, and later writers carry their notions of the Harpies so far as to represent them as most disgusting monsters,”******** to mention their depictions in Virgil’s Aeneid, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, or Hyginus’s Fabulae. This image of the harpies is an element of the novel’s peculiar poetics, as in the book “[…] cruelty and suffering seem to be inseparably connected to ugliness – and, vice versa, ugliness evokes predilection for sadism or masochism.”*********

In the novel, there is also Roland’s (and, later, David’s) horse named Scylla, which refers to either the mythical monster or a princess of Megara of the same name.

All of these classical references, as well as the fairy-tale ones, serve to show that the child’s world is built from the elements of many cultural traditions and particular texts read – and that they can play an important role in a posttraumatic psychodrama. By exposing his character to the dark and terrifying aspects of ancient narratives, John Connolly also indicates that classical antiquity was full of the elements we usually do not associate with the ideas of the child and childhood – but that they are also the elements which are inextricably linked to this cultural period.

* Weronika Kostecka, Baśń postmodernistyczna: przeobrażenia gatunku. Intertekstualne gry z tradycją literacką [Postmodern Fairy Tale: Transformations of a Genre. Intertextual Play with Literary Tradition], Warszawa: Wydawnictwo SBP, 2014, 229. All quotations translated by Maciej Skowera.

** John Connolly, The Book of Lost Things, New York: Washington Square Press, 2007, 30 (the entry is fully based on this edition).

*** Connolly, 2007, 293.

**** Connolly, 2007, 294.

***** Connolly, 2007, 110

****** Connolly, 2007, 110–111.

******* Hesiod, Theogony, 265–267, as translated by J. Banks and adapted by Gregory Nagy, available online at chs.harvard.edu (accessed: August 9, 2018).

******** Harpies (Harpyiai), available online at theoi.com (accessed: August 9, 2018).

********* Kostecka, 2014, 230.

Further Reading

Kostecka, Weronika, Baśń postmodernistyczna: przeobrażenia gatunku. Intertekstualne gry z tradycją literacką [Postmodern Fairy Tale: Transformations of a Genre. Intertextual Play with Literary Tradition], Warszawa: Wydawnictwo SBP, 2014.

Kowalczyk, Kamila, Baśń w zwierciadle popkultury. Renarracje baśni ze zbioru Kinder- und Hausmärchen Wilhelma i Jakuba Grimmów w przestrzeni kultury popularnej [Fairy Tale in the Mirror of Pop Culture: Renarrations of the Tales from the Kinder- und Hausmärchen Collection by Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm in the Space of Popular Culture], Wrocław: Polskie Towarzystwo Ludoznawcze, Stowarzyszenie Badaczy Popkultury i Edukacji Popkulturowej “Trickster”, 2016.

Russell, Annette, "Journeys through the Unheimlich and the Unhomely", RoundTable: Roehampton Journal for Academic and Creative Writing 1.1 (2017): 1–15, available online at roundtable.ac.uk (accessed: May 2, 2018).

Skowera, Maciej, “Powrót abiektu? Odrażające baśniowe krainy w Księdze rzeczy utraconych Johna Connolly’ego i Labiryncie fauna Guillermo del Toro” [The Return of the Abject? Repulsive Fairy-Tale Worlds in John Connolly’s The Book of Lost Things and Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth], in: Światy alternatywne. Monografia naukowa [Alternative Worlds: A Scholarly Monograph], Marta Błaszkowska, Katarzyna Kleczkowska, Anna Kuchta, Joanna Malita, Izabela Pisarek, Piotr Waczyński, Kama Wodyńska, eds., Kraków: AT Wydawnictwo, 2015, 155–163, available online at www.maska.psc.uj.edu.pl (accessed: May 2, 2018).

Zipes, Jack, Grimm Legacies: The Magic Spell of the Grimms’ Folk and Fairy Tales, Princeton, Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2014.