Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Michael Ende, Momo oder Die seltsame Geschichte von den Zeit-Dieben und von dem Kind, das den Menschen die gestohlene Zeit zurückbrachte. Stuttgart: Thienemann, 1972, 272 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Fantasy fiction

Fiction

Novels

Target Audience

Crossover (Older children and young adults)

Cover

We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover.

Author of the Entry:

Babette Puetz, Victoria University of Wellington, babette.puetz@vuw.ac.nz

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu

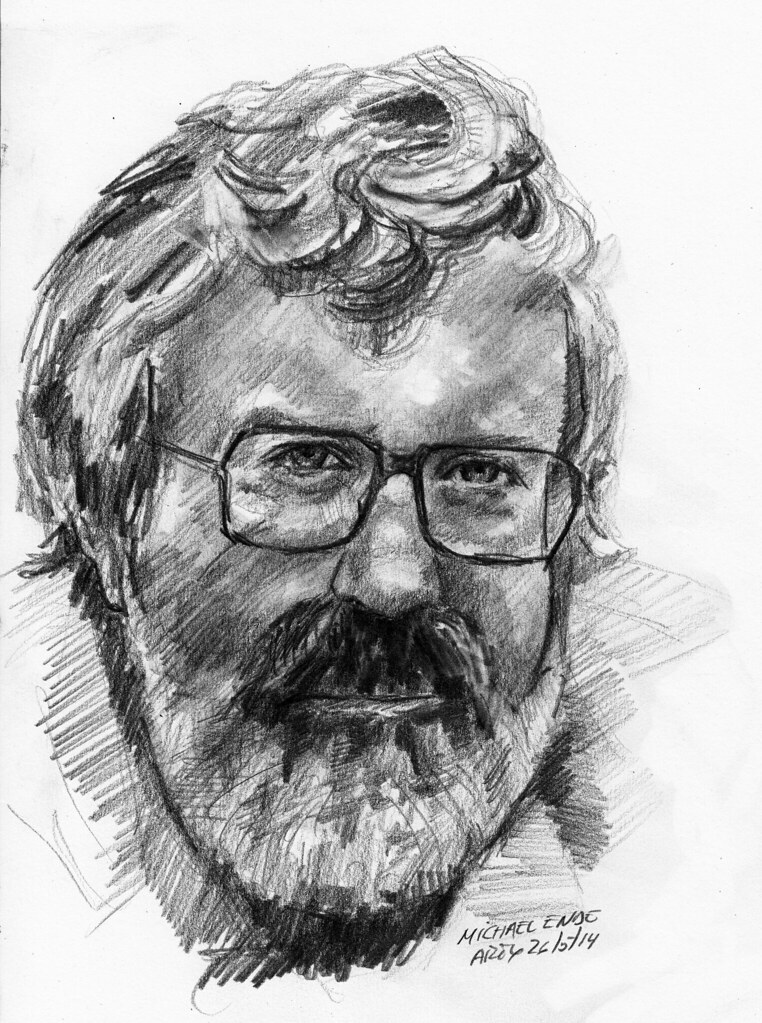

Pencil Portrait of Michael Ende by Arturo Espinosa. Retrieved from flickr.com, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 (accessed: December 28, 2021).

Michael Ende

, 1929 - 1995

(Author)

Michael Ende was born in 1929 in Garmisch-Partenkirchen (Germany). He trained as an actor in Munich and worked for small theatres in the North of Germany. From 1954, Michael Ende worked as a film critic for the Bavarian Radio and also wrote humorous scenes and songs for a political cabaret. In 1956, Ende left the theatre, experienced an artistic crisis and started writing Jim Knopf und Lukas der Lokomotivführer (Jim Button and Luke the Engine Driver) which was published in 1960 and was awarded the Deutscher Jugendbuchpreis (German YA Book Award).

In 1964, Ende married the actress Ingeborg Hoffman and the couple moved to Rome. Momo was published in 1972. In 1974, Momo was awarded both, the Deutscher und Europäischer Jugendbuchpreis (German and European YA book awards). 1975 it was made into an opera libretto with music by Mark Lothar.

Since 1976, Ende was involved with theatre again, with his Das Gauklermärchen (The Trickster’s Tale). In 1979, Die Unendliche Geschichte (The Neverending Story) was published. Ende was very displeased about the movie version and distanced himself from the project. In 1986, Momo was made into a movie.

In 1989, Ende, whose first wife had died, married Mariko Sato, who translated The Neverending Story into Japanese.

Ende wrote over 40 novels, fairy tales, stories, plays, essays, poems and non-fiction books and received 41 awards for his work. Over 20 million copies of his books have been published.

The International Youth Library in Munich has a permanent Michael Ende exhibition (accessed: September 28, 2018) which displays his entire works, as well as typescripts, letters, drawings, photos and illustrations from his books, his large personal library and other personal belongings:

Source:

Official website (accessed: September 28, 2018)

Bio prepared by Babette Puetz, Victoria University of Wellington, babette.puetz@vuw.ac.nz

Adaptations

Momo, Johannes Schaaf (director), starring: Radost Bokel, Mario Adorf, Armin Mueller-Stahl et al., 1986.

Momo alla conquista del tempo, an animated Italian film by Enzo D'Alò based on Ende's novel, 2001.

Opera:

Momo und die Zeitdiebe, opera, composed by Mark Lothar, based on Ende’s novel, 1975.

Momo and the Time Thieves, opera in two acts by Svitlana Azarova based on Ende's novel, 2017.

Audio book:

Momo, audiobook, 2005. 3 Audio-CDs, by Michael Ende (author), Klaus D Pittrich (script, director), Karin Anselm (speaker), published by: DAV, Auflage: 1. edition July 2005. (German)

- ISBN-10: 3898134709

- ISBN-13: 978-3898134705

Translation

- Afrikaans

- Czech

- Dutch

- English

- Finnish

- French

- Hebrew

- Italian

- Japanese

- Korean

- Polish

- Portuguese

- Russian

- Serbian

- Slovakian

- Slovenian

- Spanish

- Swedish

Summary

When Momo, a little girl between eight and twelve years without parents, moves into the old amphitheatre in a small town, she quickly becomes friends with the local children and grown-ups. The children love to play with Momo because her presence makes them particularly imaginative, and the adults talk to Momo about their problems because she is such a good listener.

Then everything changes: The grey gentlemen of the Timesavings Bank gain more and more power over the adults who suddenly have no more time for their own children nor for Momo. When one of the grey gentlemen visits Momo and tries to win her over with robotic doll toys, she makes him, through her special gift of listening, reveal the grey gentlemen’s secret plans. Momo tells her friends, the street-cleaner Beppo and tour-guide Gigi (in some translations he is called Guido) and the children about the grey gentlemen, and they organise a demonstration through town in order to alert the grown-ups of the fact that they are not saving their time for later, but that it is stolen and lost to them forever. The grey gentlemen realise the danger that Momo poses to their business and existence (as they live on nothing but stolen human time) and decide to silence her.

When they try to catch the little girl, she is rescued by Kassiopeia, a tortoise who can see half an hour into the future and is able to communicate with Momo by showing short written messages on her shell. Kassiopeia brings Momo to the Nowhere-House to her master Meister Hora. He teaches her about time and the plans of the grey gentlemen. Time is represented in beautiful flowers which blossom and die in an hour. Momo sleeps for a year in order to memorise and be able to sing the time-music of these flowers.

In the meantime, the grey gentlemen take all Momo’s friends away, by making the grown-ups too busy and having the children attend children’s depots instead of spending their time with Momo, playing and talking. She finds a few of them, including Gigi, but nobody has any time for her. The grey gentlemen try to persuade her to show them the way to Meister Hora’s house, so they can take over all human time in one instance, and follow her there. However, they cannot get in.

Meister Hora goes into a sleep which makes the world stand still and gives Momo one hour-flower, so she will be the only human being who can keep moving for the next hour. Now it is Momo who follows the grey gentlemen who wish to return to their headquarters and time-depot, in a panic because their supply of cigars made of the petals of human hour-flowers is running out. Momo manages to close the door to the depot by touching it with her flower, again escapes the grey gentlemen who now all dissolve into nothing because they run out of time-cigars. When all gre gentlemen have disappeared, Momo opens the door to the time depot so all the stolen time flowers can return to the humans they belong to, once Meister Hora wakes up and time re-starts. Momo is re-united with her friends and they celebrate with a feast.

Analysis

This children’s novel shows the world through the eyes of Momo, a very imaginative little girl who is puzzled by the changes in her friends who all suddenly have become short of time. Classical reception in the novel is not part of the main story, but consists mainly of its setting in an ancient amphitheatre and the names of some characters: Meister Secundus Minutius Hora (who is responsible for allotting time to humans) and his magic tortoise Kassiopeia. The reference will be to the constellation Cassiopeia which is circling the sky, and so can be used to determine the time. The constellation is based on the character Cassiopeia of Greek myth: the wife of Cepheus and mother of Andromeda. According to myth, Cassiopeia was so vain that she boasted that she was more beautiful than the 50 nereids. Neptune, in order to punish her, first had Andromeda, tied to a rock, attacked by a sea monster, and, after Andromeda’s rescue, placed her parents as constellations into the sky. Since Ende’s Kassiopeia is able to see half an hour into the future, the name might also include an allusion to the similar name of the Trojan prophetess Cassandra.

In a description of children’s imaginative play, there appear an imaginary ship Argo, an imaginary encounter with a typhoon-creature from the earliest times of Earth’s existence and an allusion to Orion. Also Meister Hora, when joking around by putting on clothes of fashions of different times, calls out: “by Orion”. This reference seems to be to the constellation Orion, rather than the hunter of Greek myth after whom it is named. The constellation Orion, as it wanders over the sky, is also used for time telling. In a different passage in the novel, two of Momo’s friends have a quarrel about a picture of Saint Antony. Furthermore, when Momo hears the “music of the stars” / “music of time”, this might allude to the Music of the Spheres of Greek philosophy, though the concept is not further elaborated on in the novel.

The novel’s setting in a ruin of an ancient amphitheatre is highlighted and explained in the first sentence of the novel. Momo’s friend Gigi takes tourists around the ruin and tells them made-up stories about it, arguing that nobody knows anyway, what happened there 1000 or 2000 years ago. We also hear that professors of Classics know of the amphitheatre.

Further Reading

Armer, Karl Michael, "Auf der Suche nach der gefrorenen Zeit. Von der Unmöglichkeit surrealistischer Literatur", in: Jacek Rzeszotnik, ed., Zwischen Phantasie und Realität. Michael Ende Gedächtnisband 2000, Passau, 2000. (= Fantasia 136/137; Schriftenreihe Band; 35), 161–167.

Böhme, Gernot, "Zeitphilosophie in Michael Endes Momo", Philosophie im Spiegel der Literatur (2007), 79–89.

Doderer, Klaus, "Michael Ende – der weite Weg in Momos Heimat", in: Klaus Doderer, ed., Reisen in erdachtes Land. Literarische Spurensuche vor Ort. Essays, München, 1998, 252–262, 310–311.

Kirchhoff, Ursula, "Michael Ende. Momo und Die unendliche Geschichte. Werkanalyse und Ortsbestimmung", Jugendbuchmagazin 1 (1984): 13–20.

Kiss, Kathrin, "Nahrung Zeit: über das Zusammenspiel zwischen Eßakten und Identität in den Kinderbüchern Pippi Langstrumpf und Momo", in: Z 4 13 (1997), 61–72.

Kulik, Nils, Das Gute und das Böse in der phantastischen Kinder- und Jugendliteratur: eine Untersuchung bezogen auf Werke von Joanne K. Rowling, J. R. R. Tolkien, Michael Ende, Astrid Lindgren, Wolfgang und Heike Hohlbein, Otfried Preußler und Frederik Hetmann, Frankfurt a. M.: 2005 (= Kinder- und Jugendkultur, -literatur und -medien; 33). (Zugl.: Univ. Diss. Oldenburg 2004).

Markert, Dorothee, Momo, Pippi, Rote Zora ... was kommt dann? Königstein / Taunus: Helmer, 1998.

Michaelis, Christiane, Michael Ende. Momo, Oldenbourg: Schulbuchverlag, 2001.

Marstaller, Sophia, "Momo – ein kleines Mädchen ganz groß", Neue Buchgeschichten (2012), 10–13.

McGowan, Moray, "Unendliche Geschichte für die Momo-Moderne?: Rezeptionskontexte zum märchenhaften Erfolg von Botho Strauß", TheaterZeitSchrift 15 (1986), 88–106.

Mikota, Jana, "Zeitdiebe in unterschiedlichen Jahrzehnten. Narratologische Untersuchungen zu Zeit – Raum – Figur in ausgewählten Beispielen" in: Kinder- und Jugendliteratur und Narratologie 2009, 67–79.

Pandikattu SJ, Kuruvilla, "Momo: Eine zeitgenössische Kritik der modernen Kultur" in Jacek Rzeszotnik, ed., Zwischen Phantasie und Realität. Michael Ende Gedächtnisband 2000, Passau 2000. (= Fantasia 136/137; Schriftenreihe Band; 35), 81–99.

Ruzicka Kenfel, Veljka, "Momo, novela cuento de hagas versus Momo, el libro de la película" in Carmen Becerra Suárez, ed., Diálogos intertextuales; 1: De la palabra a la imagen, Frankfurt am Main, 2010, 81–93.

Ruzicka Kenfel, Veljka, "Poetización de la vida: aspectos románticos en Momo y La historia interminable de Michael Ende" in: Gabriel Oliver, ed., Romanticismo y fin de siglo, 1992, 401–407.

Sahmel, Karl-Heinz, "Momo oder: Pädagogisch relevante Aspekte des Problems der Zeit", Pädagogische Rundschau 42 (1988), 403–419.

Staesche, Monika, "Momo" in Jacek Rzeszotnik, ed., Zwischen Phantasie und Realität. Michael Ende Gedächtnisband 2000, Passau 2000 (= Fantasia 136/137; Schriftenreihe Band; 35), 245–247.

Addenda

In English also known as: The Grey Gentlemen or The Men in Grey.