Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Marisa Decastro, Πάμε στην Κρήτη; [Páme stīn Krī́tī?], Short City Guides [Μικροί Οδηγοί Πόλεων (Mikroí Odīgoí Póleōn)]. Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2009, 32 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Guidebook

Illustrated works

Target Audience

Children (reader: 7+ )

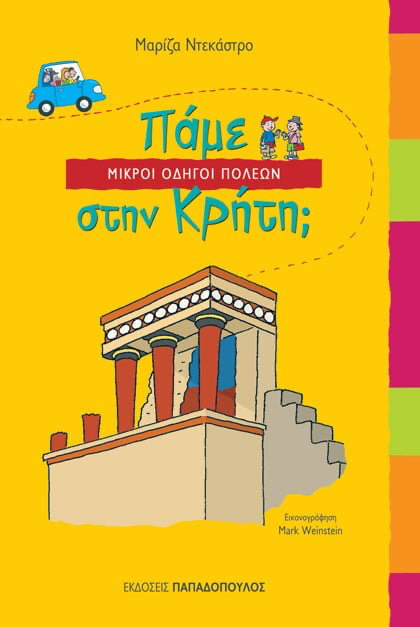

Cover

Courtesy of the Publisher. Retrieved from epbooks.gr (accessed: July 5, 2022).

Author of the Entry:

Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

Marisa De Castro

, b. 1953

(Author)

Marisa De Castro was born in Athens and was educated at the Sorbonne, Paris. De Castro, who has worked as a primary-school teacher, has written a large number of children’s books, mostly about art history and archaeology.

Sources:

Profile at the epbooks.gr (accessed: July 3, 2018).

Profile at the metaixmio.gr (accessed: July 3, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Translation

English: Let's Go to Crete! trans. by Karen Bohrer, Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2009, 32 pp.

Summary

Marisa Decastro and Mark Weinstein take young children and their guardians on a sightseeing tour of Crete, which is, as we read in the opening page, Greece’s largest island. Children are encouraged to mark places of interest on a sketch-map of Crete. The exploration of Crete starts with its diverse landscapes. These range from high mountains with gorges to plains with olive groves. Mention is made of the Cretan ibex, the so-called “kri-kri”, an indigenous wild goat. The description of islands near the shores of Crete includes a reference to “the island of Calypso”, Ogygia. Then follows a historical overview of Crete from Minoan to modern times, specifically to 1913 when Crete, freed from the Ottoman rule, became part of Greece.

A section that is labelled “Myths” appears straight after the overview, and before the discussion of Minoan antiquities. Readers learn about multiple mythological characters, who are somehow interrelated. Rhea took her son Zeus to Mount Ida to protect him from his father, Cronus. Disguised as a bull, Zeus brought the princess Europa to Crete and married her, and they had three sons, Radamanthus, Sarpedon, and Minos. King Minos asked Daedalus to build the labyrinth for the Minotaur, who was killed by Theseus. Less related is the story about the giant Talos who walked around the island.

The portrayal of Minoan architecture and artefacts that follows includes references to the labyrinth. With their many rooms the palaces at Knossos and Malia resemble labyrinths. Next comes a presentation of landmarks in modern cities, such as fountains, fortifications, and mosques. Once again, there is a reference to Classical mythology, namely that Athena and Artemis used to bathe in Lake Voulismeni at Aghios Nikolaos.

We read about notable male figures in the island’s history. These include the English archaeologist Arthur Evans who discovered “the Palace of Minos”. A more fictional section follows about sights that are associated with fairy tales. The book closes with a presentation of ancient and modern art, ranging from Minoan frescoes to traditional embroidery. In educational activities, children are asked to write a serenade and to embroider a pillow with Cretan motifs. At the end of the book, we find simple recipes, and a list of shops for Cretan products, notably, cheese, olive oil, and wine.

Analysis

The book addresses an English-speaking audience. The content is exceptionally rich, and it may appeal to readers who are already familiar with Greek culture, ancient and modern. The island of Crete emerges both as a microcosm of Greece – as it is customarily appreciated by tourists internationally – and an area of particular interest for those who wish to deepen their knowledge of Greek landscapes, antiquities, and folklore.

On the one hand, there is a multi-ethnic flair in the book. There is an emphasis on the island’s Venetian and Ottoman architectural landmarks. Moreover, we read about famous personalities of world culture, such as El Greco (Renaissance painter), Arthur Evans (British archaeologist), and Mikis Theodorakis (renowned composer). On the other hand, antiquities and traditions are quite local in their uniqueness. No other area in Greece can boast Minoan palaces and traditional serenades, the so-called “mantinades”.

Classical mythology also appears to assume local signification. The myths of Rhea and Zeus, Europa and the bull, the Minotaur, and Talos are all played out in the physical and imaginary landscape of Crete. The labyrinth, in particular, is a remarkably Cretan feature, as alluded to by the complex architectural plans of Minoan palaces. Archaeological discoveries might appear to be offering hard evidence for the existence of the mythical labyrinth. In the book’s pictorial narrative, nonetheless, there is no distinction between fact and fiction.

Mark Weinstein’s illustrations are simple, and reminiscent of graphic design and comics. The style and colour tones are the same for depictions of mythical characters and of archaeological finds. Weinstein’s illustration of Cretan myths connects different episodes into one picture (pp. 12–13). From left to right, we see Europa riding a bull, Rhea with baby Zeus in a cave, Theseus combating the Minotaur, and Talos carrying a boulder. When looking at the beautifully executed picture, one might get the impression that, like the sea, mythology engulfs Crete from all sides so that all mythical actors safeguard the island’s cultural uniqueness.

It would appear to be the case that mythology is offered to readers as a fictional story. Thus, for the island of Gavdos, which lies to the far south of Crete, we read that “they say that this was Ogygia, the island of Calypso” (p. 8). Ogygia is known from the Odyssey (Hom. Od. 1.85). The Homeric poems may have added credence to myth. Appropriately for a book targeting children as young as seven, however, there is no citation of ancient texts. Instead, children may be prompted to liken Classical myth to folktales about fairies, and the cave of fairies, Neraidospilios, at Astraki, as they read in subsequent pages of the book (p. 23).

Further Reading

Information about the book:

Addenda

A comprehensive presentation of the island of Crete, from antiquity to modern times. The book was first published in Greek in 2009, and is part of a series of 5 city guides. The translation is by Karen Bohrer.

The entry is based on the English edition:

Marisa Decastro, Let’s Go to Crete!, trans. by Karen Bohrer, Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2009, 32 pp.