Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

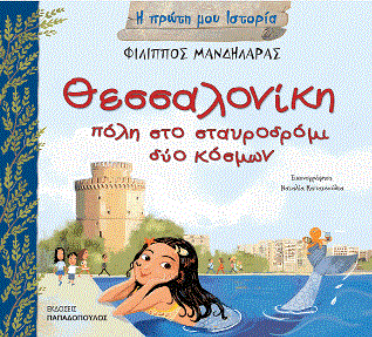

Filippos Mandilaras, Θεσσαλονίκη, πόλη στο σταυροδρόμι δύο κόσμων [Thessaloníkī, pólī sto stavrodrómi dýo kósmōn], My First History [Η Πρώτη μου Ιστορία (Ī prṓtī mou Istoría)]. Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2018, 36 pp.

ISBN

Available Onllne

Demo of 7 pages available at epbooks.gr (accessed: October 13, 2021).

Genre

Illustrated works

Target Audience

Children (5+)

Cover

Courtesy of the Publisher. Retrieved from epbooks.gr (accessed: July 5, 2022).

Author of the Entry:

Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

Natalia Kapatsoulia (Illustrator)

Natalia Kapatsoulia studied French Literature in Athens, and she worked as a language tutor before embarking on a career as a full-time illustrator of children’s books. Kapatsoulia has authored one picture book Η Μαμά πετάει [Mom Wants to Fly], which has been translated into Spanish Mamá quiere volar. Kapatsoulia, who now lives on the island of Kefalonia, Greece, has collaborated with Filippos Mandilaras on multiple book projects.

Sources:

Official website (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Profile at the epbooks.gr (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Filippos Mandilaras

, b. 1965

(Author)

Filippos Mandilaras is a prolific and well-known writer of children’s illustrated books and of young adults’ novels. Mandilaras studied French Literature in Sorbonne, Paris. His latest novel, which was published in May 2016, is entitled Υπέροχος Κόσμος [Wonderful World], and it recounts the story of teenage life in a deprived Athenian district. With his illustrated books, Mandilaras aims to encourage parents and teachers to improvise by adding words when reading stories to children. Mandilaras is interested in the anthropology of extraordinary creatures and his forthcoming work is about Modern Greek Mythologies.

Sources:

In Greek:

Profile on EP Books' website (accessed: June 27, 2018).

i-read.i-teen.gr (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Public Blog, published 15 September 2015 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Press Publica, published 28 January 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Linkedin.com, published published 6 May 2016 (accessed: February 6, 2019).

In English:

Amazon.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

On Mandoulides' website, published 7 March 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

In German:

literaturfestival.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Summary

The book starts by mentioning the different peoples that have lived in Thessaloniki. The city is said to have been named by Cassander, one of Alexander the Great’s successors, after Alexander’s sister, who was a mermaid. Cassander founded Thessaloniki as a great trading port. The Romans built a road that connected East with West, as well as palaces and arches. Later, we are told, when Constantinople became a capital city, Thessaloniki served as a co-capital city. Thessaloniki was besieged on multiple occasions by different peoples. When the Byzantine Empire was in decline, spiritual life flourished in Thessaloniki. New and elaborate churches and monasteries emerged, and theologians taught people of varied ethnic backgrounds. We then learn that decline came with the city falling to the Ottomans (1430 CE). Then, Jews from Spain came to Thessaloniki. Trade flourished again, and the population was multi-cultural. When times changed again (19th century), many people valued Thessaloniki. For the Jews, Thessaloniki was the Jerusalem of the Balkans. The Greek army entered the city in 1912. Again, adventures befell the city, with a fire in 1917, the arrival of refugees from Asia Minor in 1922, and the deportation of Jews in World War II. Today, Thessaloniki is a vibrant place, but everything reminds us of its long history.

Analysis

Mandilaras offers a concise, informative, and balanced account of Thessaloniki’s history, from its foundation in Hellenistic times (the date 316 BCE is given) to the modern era. The main message in the textual narrative is that changing population dynamics and multiculturalism drive historical change. Different peoples came and went in Thessaloniki. What is left behind is massive construction projects, such as Roman roads, fortifications, and churches. The physical presence of grand architecture, therefore, contrasts with the invisibility of people who lived in Thessaloniki in the past, and whose presence readers need to recover by educating themselves about history.

Dates are given for key events, as well as for historical periods (e.g., 168 BCE to 3rd century CE for Roman times). The periodization may help with children’s learning of history in their schooling later on in life.

Throughout the ages, and besides multiculturalism, there appears to be an emphasis on trade and communications. The book’s subtitle labels Thessaloniki as a city at a crossroads. We read that travellers, merchants, and cargo ships arrived in Thessaloniki’s port. Evidently, the city amassed wealth through the sea. A parallel can be drawn here with another book in the same series about the Cycladic islands Κυκλάδες. Πετράδια στο Αιγαίο [The Cyclades: Jewels in the Aegean, my translation],* in which seafaring is glorified. Thessaloniki and the Cyclades, notwithstanding their unique geographical configuration, seem to serve as case studies in learning about broad themes in history, especially about movements of people, cultural exchanges, and trade in goods.

Remnants such as the Via Egnatia, the Roman Road that connected East with West in southern Balkans, and the many churches of Thessaloniki make the city important for its cultural heritage from Roman times onwards. Indeed, the general public in Greece and abroad tends to associate Thessaloniki with Byzantine art and archaeology. Hence, there is no mention in the book of Archaic and Classical settlements in the Thermaic Gulf, the excavation of which has yielded a wealth of fine objects in recent years and exhibitions in the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki. Finds from the cemetery of Sindos, in particular, have received considerable attention, both in academia and in public engagement events.**

The city’s name, nonetheless, relates to the Classical past, and its afterlife. Thessaloniki lives on after her brother’s death (323 BCE), which marks the end of the Classical era. She is a historical figure, as Alexander’s sister and Cassander’s wife. Yet, Thessaloniki is described in the text also as a mermaid. The illustration shows a young woman submerged in the sea asking the captain of an ancient Greek trireme whether Alexander is alive. The captain replies affirmatively. The story here draws from a popular legend in Greek folklore. According to this legend, Thessaloniki wanted to kill herself after Alexander’s death and threw herself in the sea. Since Alexander had bathed his sister’s hair in immortal water, however, Thessaloniki did not drown, but turned into a mermaid. She intercepted marine traffic and asked the sailors a formulaic question, as we read in the illustration here: “Is King Alexander alive?” (Ζει ο βασιλιάς Αλέξανδρος;). The formulaic answer had to be: “He lives and reigns and conquers the world!” (Ζει και βασιλεύει και τον κόσμο κυριεύει!). A different response, namely, that Alexander had died, would enrage the mermaid, and she would sink the boat and its crew.

The legend has been influential in modern Greek artistic and literary output. The mermaid is featured in multiple paintings, novels, and poems, including works by celebrated and world-famous figures such as the painter Yannis Tsarouchis (Mermaid, 1955)*** and the writer Nikos Kazantzakis (Capetan Michalis, 1953), whose lyrics have been turned into a song.**** It is with good reason that Kapatsoulia places the mermaid on the book’s front cover. A creature that was inspired by Classical antiquity entices readers to visit Greece’s second largest city.

* The Cyclades: Jewels in the Aegean [Κυκλάδες. Πετράδια στο Αιγαίο (Kykládes. Petrádia sto Aigaío)].

** See, for example (accessed January 29, 2019).

*** See (accessed January 29, 2019).

**** See (accessed January 29, 2019).

Further Reading

Information about the book:

epbooks.gr/product.asp?catid=101733&title=(accessed February 12, 2019).

Addenda

Published in Greek, 15 October 2018. Hardbound.