Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Wojciech Mohort-Kopaczyński, Dawno temu w Helladzie. Mity greckie w wyborze dla dzieci, ill. Kazimierz Rojowski. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Edukacyjne, 2000, 68 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Anthology of myths*

Target Audience

Children

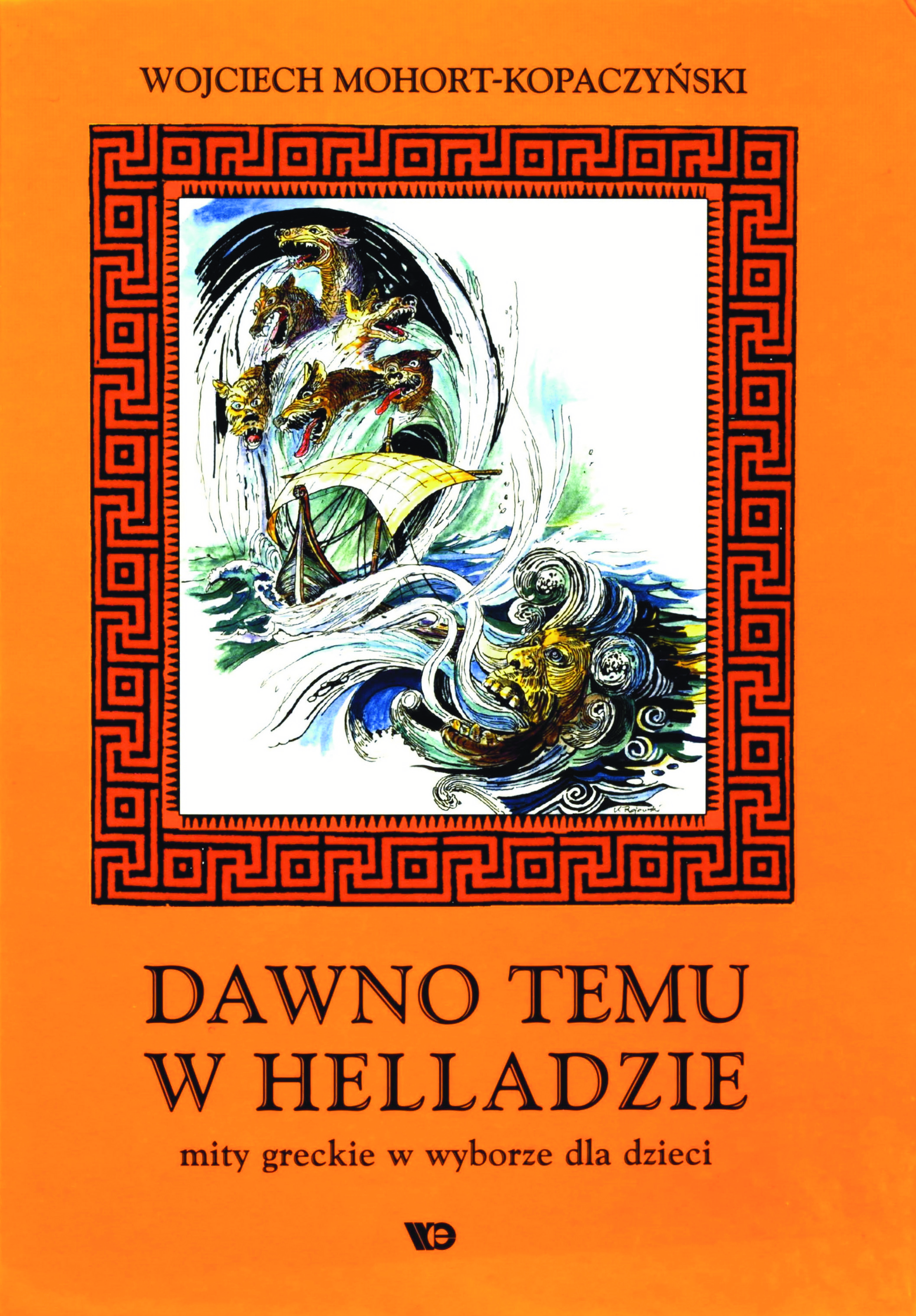

Cover

Cover design by Kazimierz Rojowski. Courtesy of the publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Maria Kruhlak, University of Warsaw, maria.kruhlak@student.uw.edu.pl

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Photograph courtesy of the Author.

Wojciech Mohort-Kopaczyński

, b. 1960

(Author)

MA in Classical philology, Adam Mickiewicz University of Poznań. Affected by consecutive educational reforms, currently teaches Latin and Ancient Culture at the Piarist Fathers’ High School in Cracow. Co-author, with Teodozja Wikarjakówna, of high school Latin textbooks Disce Latine 1–2; author of Dawno temu w Helladzie. Mity greckie w wyborze dla dzieci [A Long Time Ago in Hellas. Selection of Greek Myths for Children], 2000, a collection of popular Greek myths adapted for children, and Starożytne ABC [Ancient ABC] also for children (unfortunately still in the desk drawer); translator (for a handful of grown–ups) of Aenigma fidei, Speculum fidei, Epistola ad fratres de Monte Dei by William of St-Thierry and of De miraculis by Peter the Venerable; these works were translated for the Publishing House of the Benedictines in Tyniec (the oldest Benedictine Abbey in Poland, near Cracow). Among the translations, two minorum gentium: John Scotus Eriugena’s Homily on the Prologue to the Gospel of St. John and the First Sermon on the Song of Songs by St-Bernard of Clairvaux.

Source:

Bio kindly provided by the Author.

Bio prepared by Maria Kruhlak, University of Warsaw, maria.kruhlak@student.uw.edu.pl

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp., section by Maria Kruhlak, p. 215.

A collection of the best known Greek myths developed and adapted for children. It introduces the world of myths for children who are encountering mythological stories for the first time. In this case, myths are treated as tales with a moral. Stories are adapted to the young age of the readers and written with sensitivity, without emphasizing violence. Myths become a universal medium that allows communicating to children the difference between right and wrong behaviour. Stories easily capture the imagination, and rich illustrations enhance that effect. Each of the twelve stories ends with four lines that rhyme and are moralistic. Only the last one about Odysseus's journey is entirely in verse, perhaps in deference to Homer’s Odyssey.

Analysis

The collection adapts Greek myths in a convention of short bedtime stories, seen here as a tale with a moral rather than a myth with its complexity and details. From the very beginning, the author introduces some basic elements of Greek antiquity. Any new, different, difficult terms or issues are explained in the footnotes (for example, what does a laurel wreath mean, who is a hero, what does a lyre look like?). The collection presents: the myth of Perseus, Apollo and the Muses, Persephone’s abduction, Daedalus and Icarus, Midas, the Sphinx’ riddle, the Augean stables, the judgement of Paris, and Odysseus’ journey.

The convention of simplifying well known myths to adjust their content for younger children includes removing any violent elements. If some remain (like Medusa’s slaying or Icarus’ fall), they are just mentioned and not described in detail. The author slightly modifies some myths to avoid drastic details or to soften the situation. Thus, Hades understands Persephone’s homesickness and has remorse after abducting her; consequently, he proposes to let her stay at home for some time during the year. Also, the character of the Minotaur is shown to be less vile. He is said to be a bizarre creature with an annoying habit of making noise at night. The creature does not devour humans, thus, Minos, in the convention of a folktale, promises the hand of his daughter, the princess, to anyone who can silence the creature. Theseus comes, tempted by the reward, and is given a thread, comes back and marries the princess – the information that he slew the Minotaur is not provided as it was not intended to be his quest. The Oedipus myth is simplified as well – the hero comes to free Thebes from the Sphinx, solves the riddle and becomes king – which glosses over all of the difficult elements of the story. Similarly, Heracles does the job for Augeas for the price of 1/5 of his horses, is given his payment and goes away without any indication that Augeas’ reluctance to pay cost him his life.

The only human characters who are described as dying are Icarus and Paris. Icarus’ death is presented as a result of his disobedience, which is highlighted by a moral advising children that they should always listen to their parents or later regret their disobedience. Paris’ death is barely mentioned along with the other victims of the Trojan war who did not return home, a euphemism suggesting he could just as well be missing.

Unconventional, against the background of other myths, the story of Odysseus’ journey and his seven chosen adventures are written in verse. The author does not use the previously followed template of 2-page-long stories but tries to stylize his narration like an epic. He does not write in hexameter verses as Homer did but rather patterns the poem on a rhymed 11-syllabes-long verse.

What adds to the educational value of the book are the inside covers. The front inside cover contains the map of ancient Greece with the main locations of the action marked: Olympus, Troy, Thebes, Athens, Alphaeus river, Icaria and Crete. The back inside cover shows a board game Following Odysseus, which facilitates memorization of places and characters visited by Odysseus.

Further Reading

Jubileusz 10-lecia Liceum Ogólnokształcącego w Piekarach, misjonarze.org (accessed: March 27, 2013, link expired).

Mohort-Kopaczyński, Wojciech and Teodozja Wikarjakówna, Disce Latine 1. Podręcznik do języka łacińskiego dla szkół średnich. Kurs podstawowy, Warszawa-Poznań: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 1996.

Mohort-Kopaczyński, Wojciech and Teodozja Wikarjakówna, Disce Latine 1. Podręcznik do języka łacińskiego dla szkół średnich Kurs poszerzony, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Szkolne PWN, 1998.