Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Stephanie Meyer, Midnight Sun. New York: Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, 2020, 658 pp.

ISBN

Official Website

Author's website (accessed: August 10, 2021).

Genre

Fantasy fiction

Target Audience

Young adults

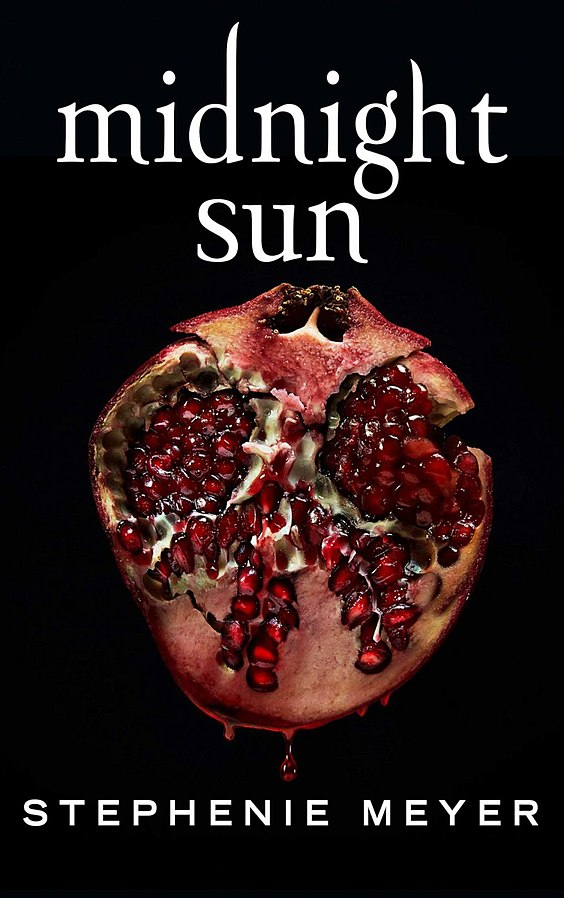

Cover

Cover uploaded by B.douu. Retrieved from Wikipedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 (accessed: February 7, 2022).

Author of the Entry:

Aimee Hinds, University of Roehampton, hindsa@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

Stephenie Meyer by Gage Skidmore. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 (accessed: January 5, 2022).

Stephenie Meyer

, b. 1973

(Author)

Stephenie Meyer was born 1973 in Hartford, Connecticut, and was raised in Arizona. She attended Brigham Young University, graduating with a Bachelor of Arts in English. She is a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Days Saints and strictly follows her Mormon faith. Her religious beliefs show in her works. Her first novels were the Twilight saga (four books released annually, 2005 through to 2008). Meyer claims that the premise of the books came to her in a dream. Meyer has also published other novels, supplementary literature and a novella to the Twilight saga, and as well as being involved in smaller video and film projects, maintaining a blog, and continuing to write more books. She is married, with three children, and lives in Cave Creek, Arizona.

Sources:

Official website (accessed: September 12, 2019).

Profile at Wikipedia (accessed: September 16, 2019).

Bio prepared by Tim Atkins, Victoria University of Wellington, timjosephatk@gmail.com

Translation

Bosnian: Ponoćno sunce, trans. Danko Ješić, Buybook, 2020.

Bulgarian: Среднощно слънце [Srednoščno sl'ntse], trans. Desislava Nedialkova, Egmont, 2020.

Catalan: Sol de mitjanit, trans. Alexandre Gombau Armau, Aïda Garcia Pons, & M. Dolors Ventós Navés, 2020.

Chinese: 午夜陽光, trans. 史蒂芬妮·梅爾, 甘鎮隴, 尖端出版, 2021.

Croatian: Ponoćno sunce, trans. Marko Maras, Lumen, 2020.

Czech: Půlnoční slunce, Egmont, 2021.

Danish: Midnatssol, CarlsenPuls, 2020.

Dutch: Midnight Sun, Unieboek | Het Spectrum, 2020.

Estonian: Keskööpäike, Pegasus, 2020.

Finnish: Keskiyön aurinko, trans. Ilkka Rekiaro and Päivi Rekiaro, WSOY, 2020.

French: Midnight Sun, trans. Luc Rigoureau, Hachette, 2020.

German: Biss zur Mitternachtssonne, trans. Sylke Hachmeister, Annette von der Weppen, & Henning Ahrens, Carlsen, 2020.

Greek: Ο ήλιος του μεσονυκτίου [O ī́lios tou mesonyktíou], trans. Foteinī́ Moschī́, Psychogiós, 2020.

Hungarian: Midnight Sun – Éjféli nap, Könyvmolyképző, 2021.

Indonesian: Midnight Sun, trans. Rosi L. Simamora, Gramedia Pustaka Utama, 2020.

Italian: Midnight Sun, Fazi, 2020.

Latvian: Pusnakts saule, trans. Ieva Elsberga, Zvaigzne ABC, 2021.

Lithuanian: Vidurnakčio saulė, Alma littera, 2021.

Polish: Słońce w mroku, trans. Donata Olejnik, Wydawnictwo Dolnośląskie, 2020.

Portuguese: Sol da Meia-Noite, trans. Maria Silva, Intrínseca, 2020.

Slovak: Polnočné slnko, trans. Lucia Halová, Tatran, 2021.

Spanish: Sol de medianoche, Alfaguara, 2020.

Swedish: Midnattssol, B. Wahlströms, 2020.

Turkish: Gece Yarısı Güneşi, trans. Tuba Özkat, Epsilon Yayınevi, 2020.

Vietnamese: Mặt Trời Lúc Nửa Đêm, NXB Trẻ, 2020.

Sequels, Prequels and Spin-offs

Twilight, 2005.

New Moon, 2006.

Eclipse, 2007.

Breaking Down, 2008.

Life and Death: Twilight Reimagined, 2016.

Summary

The novel is a retelling of the first and nominal book of the "Twilight" series from the perspective of the vampire Edward Cullen; the reader no longer gets any insight into the thoughts of Bella Swan (the narrator of Twilight), and so the novel opens with a description of Edward and Bella's first meeting, which is the first point at which we meet Edward in Twilight. After an awkward period at school during which Edward is convinced that he may kill Bella, he saves her from being crushed by a car and they begin dating. The novel culminates with an attack on Bella by the nomadic vampire James, who almost kills her; she is saved by Edward and his family.

While Midnight Sun follows the same plot as the 2005 novel Twilight (and as such shares scenes and even dialogue with the earlier novel), the insight into Edward's world hugely expands the work by around 200 pages. One of the most significant changes is the addition of the Hades and Persephone myth as a recurring theme, which Edwards mentions to several times in reference to himself, Bella and their relationship. The cover image – an opened, dripping pomegranate - foregrounds the receptive nature of the text and refers back to the cover of the original novel, which was a red apple held in two hands.

Analysis

Although the novel faithfully retells the same story as Twilight, a fresh twist is added by the classical allusions to Hades and Persephone. The references are explicit in this novel, although the similarities between the Persephone tale and Twilight have been noted by Holly Blackford who compares Bella's cycling between her divorced parents Renee – in perpetually sunny Arizona – and Charlie – in overcast and wet Forks, where she meets Edward – to the inevitable cycling of Persephone between Demeter and Hades.*

The parallels with the myth first occur to Edward as he takes Bella out for a meal early in the narrative. Edward, who as a vampire does not eat or drink human food, commands Bella to drink, recalling Persephone's eating of the pomegranate seeds in both the Homeric hymn to Demeter and Ovid's Metamorphoses. As he watches her, he is reminded of Persephone:

"Suddenly, as she ate, a strange comparison entered my head. For just a second, I saw Persephone, pomegranate in hand. Dooming herself to the Underworld. Is that who I was? Hades himself, coveting springtime, stealing it, condemning it to endless night."

From this point, Edward regularly refers to himself as Hades and expresses concern that his relationship with Bella will doom her to the "Underworld", which Edward uses as a metaphor for both death and the secretive life he lives with his vampire family. His identification with Hades extends to an association between Bella and Persephone, which is also continued throughout the novel. Edward uses Persephone to refer to both Bella's mortality and her vulnerability. The use of Persephone illustrates a fairly close engagement with at least one ancient source text, especially as Edward closely associates Bella with Persephone during an outing at which he plans to reveal the extent of his vampiric nature to her by taking her to a secluded meadow:

"She walked almost reverently into the golden light. It gilded her hair and made her fair skin glow. Her fingers trailed over the taller flowers, and I was reminded again of Persephone. Springtime personified.

I could have watched her for a very long time, perhaps forever, but it was too much to hope that the beauty of the place could make her forget the monster in the shadows for long."

The meadow motif is common to ancient mythic tales involving sexual assault; aside from Persephone, these include Creusa in Euripides' Ion and Europa in Moschus' Europa. In the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, Persephone is picking flowers in a meadow when Hades abducts her, using a huge, gleaming narcissus as a lure (pp. 8–10); similarly, Edward takes Bella to a meadow to show her his gleaming skin, the reason why vampires must remain out of the sun.

Like ancient versions of the Persephone myth, the pomegranate seeds are also a recurring image, and here they also carry a sexual implication. Edward and Bella never consummate their relationship during the novel – they abstain from sex until they are married, described in the "Twilight" novel Breaking Dawn – even though they both clearly physically desire each other; both Midnight Sun and Twilight make it clear that it is Edward's fear of hurting Bella that stops them (although the fact that they consummate their marriage despite Bella still being human is evidence that it is Meyer's desire not to have her characters engage in sex before marriage that is the primary concern here). After Edward has revealed his nature to Bella, she expresses regret that they cannot be together forever, and Edward realises that they are fundamentally incompatible, worrying:

"This was a dangerous path to even hint at. Hades and his pomegranate. How many toxic seeds had I already infected her with?"

He expresses a similar sentiment near the end of the novel, after having to save Bella's life following the attack on her by another vampire:

"Pomegranate seeds and my underworld. Hadn't I just witnessed a brutal example of how badly my world could go wrong for her? And she was lying here broken because of it."

This scene in Twilight (which does not include the explicit Hades reference) is noted by Blackford as a confrontation between Renee, a Demeter figure as Bella's mother, and Edward-as-Hades;** Blackford notes Renee's ineffectiveness as a Demeter figure and suggests that this role is taken on by Bella's friend and love interest Jacob.*** Owing to the novel being dominated by Edward's perspective, we meet Jacob very little in Midnight Sun, leaving Renee as the only Demeter figure. Demeter's ineffectuality is a common feature of modern Persephone receptions which position her bad parenting as a reason for Persephone falling for Hades (often after running away from her mother); this is the case in the popular webcomic Lore Olympus by Rachel Smythe, the comic Epicurus the Sage by William Messner-Loebs and Sam Kieth and the novel Olympian Confessions: Hades and Persephone by Erin Kinsella. Rather than dealing with the Demeter character, as these receptions do, Midnight Sun virtually ignores her, focusing instead on Bella-as-Persephone's own choice and agency in pursuing a relationship with Edward-as-Hades.

As well as using the myth to hide the sexual desires of her characters, Meyer also uses it to underscore traditional gender roles. One of the ways Persephone is used to compare to Bella is in her vulnerability, while Edward as Hades holds the position of power in the relationship. This unbalanced power dynamic is present in ancient versions of the myth: Hades is a major deity and Persephone's uncle, and has requested her as a bride from her father Zeus, which in ancient terms makes his actions lawful (see Carey 1995 and Harris 1990 in "Further Reading" for further discussion of rape as a crime in ancient Athens). In Midnight Sun, the power differential is present – Bella is a seventeen-year-old high school student, while Edward is one-hundred-and-three and merely poses as a student to appear human. Edward frequently exploits this power by using his long life experience to decide what is best for Bella. While this is a feature of Twilight, the link with Hades and Persephone is made explicit in Midnight Sun.

While the glossing of rape from the Persephone myth is unsurprising given that the audience is young adults, the result is a reading of the Persephone myth which glosses the problematic aspect of her non-consensual abduction and rape, and replaces it with a romantic tale in which the Persephone character in Bella is (at least to some extent) included in decisions by her romantic partner. There is a particular issue in the excusing of some of Edward's questionable and stereotypically abusive behaviour as romantic or concern for Bella – for example, Edward stalks Bella and is therefore present to be able to stop her being attacked by a rapist – and the mythic allusions are pulled into service in justifying his behaviour.

Despite the problematic usage of the myth, the paralleling of Bella with Persephone to denote the pull of the underworld – as a metaphor for death, either conventional or as a vampire – is reminiscent of the positioning of women and girls who died before marriage as either brides of Hades or as the virginal Persephone in ancient Greek contexts.**** Romance aside, it is made clear in the novel through the prescient visions of Edward's sister Alice that Edward only has two choices with Bella: to be with her, or to kill her. Although he is not aware during this early stage, being with Bella eventually leads to her becoming a vampire, and thus both paths lead to Bella's death

As well as the frequent references to Persephone and Hades, there are also several nods to other classical motifs including the idealised beauty of both Edward and Bella. Bella is referred to by Edward as "something halfway between a goddess and a naiad", and Edward also mentions her natural beauty as something that women have other women can only attempt to attain through cosmetics, again pointing to the idealising of traditional gender roles. The vampires are described as having pale, hard, marble-like skin, as they are in Twilight, inviting comparison with classical sculptures; this is underscored by the inside cover image depicting Canova's Cupid and Psyche, and brings to mind the myth of Pygmalion in which the sculptor Pygmalion falls in love with his own marble creation, later brought to life by Aphrodite; this metamorphosis is of course not realised in either Twilight or Midnight Sun, but it is somewhat brought to pass in reverse in Breaking Dawn when Bella is finally turned by Edward into a vampire.

* Blackford, Holly, The Myth of Persephone in Girls' Fantasy Literature, Routledge: New York & Oxon, 2012, 203–204.

** Ibidem, 204.

*** Ibidem, 207.

**** Mackin, Ellie, "Girls Playing Persephone (in Marriage and Death)", Mnemosyne 71.2 (2018): 209–228.

Further Reading

Blackford, Holly, The Myth of Persephone in Girls' Fantasy Literature, Routledge: New York & Oxon, 2012.

Carey, C., "Rape and Adultery in Athenian Law", The Classical Quarterly 45.2 (1995): 407–417.

Harris, Edward M., "Did the Athenians Regard Seduction as a Worse Crime Than Rape?", The Classical Quarterly 40.2 (1990) 370–377.

Hinds, Aimee, "Rape or Romance?: Bad Feminism in Mythical Retellings", Eidolon (2019) (accessed: May 27, 2021).

Mackin, Ellie, "Girls Playing Persephone (in Marriage and Death)", Mnemosyne 71.2 (2018): 209–228.