Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Jadwiga Żylińska, Mistrz Dedal. Warszawa: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza RSW „Prasa–Książka–Ruch”, 1973, 59 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Adaptations

Myths

Target Audience

Children

Cover

The publisher of the text closed down in 1990 leaving no known successors, and we were unable to determine if there are any copyright holders. Including the cover in our database meets all fair use requirements, still, we invite the users to share with us any information they may have about copyrights to the posted materials.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Adam Ciołek, University of Warsaw, adamciolek@student.uw.edu.pl

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

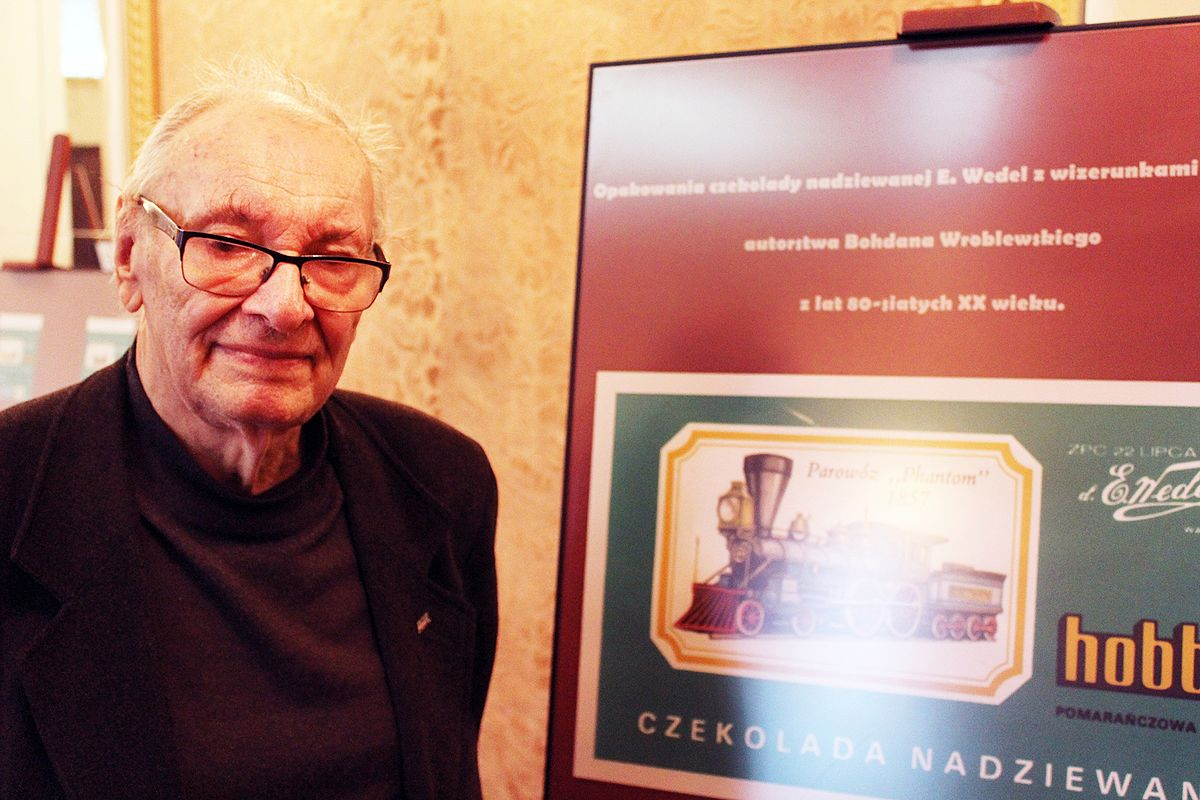

Bohdan Wróblewski by Tomasz.fedor, 2015. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 (accessed: December 22, 2021).

Bohdan Wróblewski

, 1931 - 2017

(Illustrator)

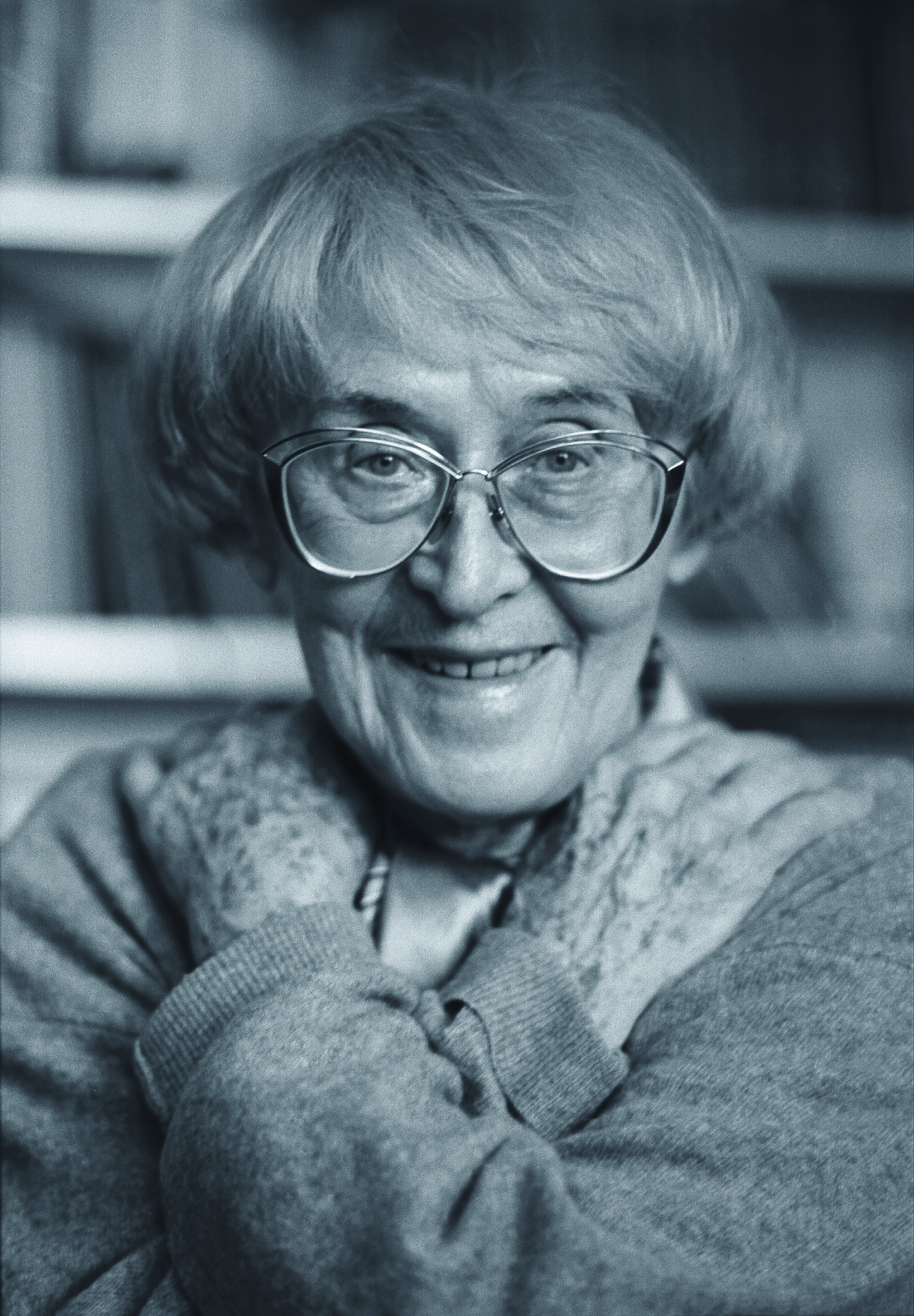

Photograph courtesy of its Author, Elżbieta Lempp.

Jadwiga Żylińska

, 1910 - 2009

(Author)

Born in Wrocław, lived in southern Wielkopolska [Greater Poland] (Ostrzeszów and Ostrów Wielkopolski), which influenced her later life. Graduated in English philology from the University of Poznań. Proficient in Latin, ancient Greek, English, and French. For many years worked for the Polish Radio. Prose writer, essayist, author of screenplays, radio dramas, historical novels, and books for children and young readers. Well known as an author of historical novels written from a woman’s point of view (the most important among these is a 2-volume novel Złota włócznia [The Golden Spear], 1961–1964). She made her debut in 1931 with a story for children Królewicz grajek [The Prince Piper] published in a periodical (still under her maiden name Michalska). Since 1964 member of the Polish PEN Club, in 1993 received the Polish PEN Club prize for lifetime achievement as a prose writer. Decorated with the Knight’s Cross of Polonia Restituta for outstanding achievements for Polish culture. Some of her books were translated into German and Russian. She is the author of a cycle Oto minojska baśń Krety [Here is the Minoan Tale of Crete], 1986, parts of which were also published separately.

Source:

Żylińska Jadwiga, in: Jadwiga Czachowska; Alicja Szałagan, eds., Wspołcześni polscy pisarze i badacze literatury. Słownik biobibliograficzny, vol. 10: Ż, Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 2007, pp. 66–69.

Bio prepared by Gabriela Rogowska, University of Warsaw, g.rogowska@al.uw.edu.pl

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

It is the life story of Daedalus beginning from his first visit to an Athenian blacksmith. The young Daedalus, a descendant of Erechtheus, king of Athens, starts to learn his craft locally and still, as an apprentice, quickly becomes famous for his inventions and skills. After killing Talos, his talented rival and nephew, Daedalus, is convicted and banished. He travels to Crete, where his skills win the recognition and favour of king Minos and queen Pasiphaë. He builds a Labyrinth as a new wing for the royal palace and produces a statue of a man with the head of a bull, called the “Minotaur.” Eventually, Daedalus loses the king’s favour and, with his son, Icarus, flees from Crete using his invention, a flying contraption similar to wings. Icarus falls into the sea and dies. Minos pursues the fugitives but is killed during the pursuit at the court of the Sicilian king Cocalus, where Daedalus was hiding. Finally, Daedalus dies on Sardinia, where he builds a system of forts and watchtowers. Żylińska also describes certain Cretan customs (e.g., bullfights) and the story of Minos’ son Androgeos as a reason for the king’s bloody retribution against Athens. She proposes a rational explanation for the origin of the myth of the Minotaur.

Analysis

Żylińska addresses her retelling of the myth of Daedalus directly to children. She starts with the words: “Do you want to hear a legend about Daedalus, a famous builder of the Labyrinth, who practiced blacksmithing and constructed the first ship which soared in the air?” (p. 5), then she cites Homer’s description of Crete and explains the phenomenon of the Cretan myth and its reception, providing information about archaeological excavations conducted by sir Arthur Evans. As Daedalus’ story is aimed at children, it begins with his childhood in Athens, his childly curiosity, persistence and brilliance resulting in new inventions made to solve interesting problems. Daedalus, as a child, resembles a normal, talented, and intelligent child who discovers the world and its rules out of curiosity. Daedalus becomes an adult, but the child’s point of view remains because the author introduces more child protagonists: Ariadne, Phaedra, three sons of Minos – Androgeos, Deucalion and Glaucus (for whom Daedalus makes extraordinary toys) – Icarus, and daughters of the king of Sicily, Cocalus.

Daedalus becomes famous, his character changes – he loses the candour and honesty typical for children and begins to envy the talent of Talos, his nephew and apprentice. The negative feelings eventually escalate into an argument, manslaughter and banishment from the native city. Żylińska does gloss over the subject of Talos’ death and Daedalus’ role in it but adapts it to the child reader, describing it as an effect of chance and not of ill will or murderous tendencies. Similarly, Daedalus bears indirect responsibility for the death of Androgeos, Minos’ son, although he was not even present in Athens when Androgeos was killed.

Between the lines, Żylińska provides lively descriptions of Crete, the Minoan civilization and the Cretan culture in general, as the background to Daedalus’ stay at the court of Minos. She also highlights the role of women in society – according to her interpretation, Pasiphaë is the hereditary ruler of Crete; the cult of the Great Goddess is even more important than that of Poseidon. Curiously, while retelling the myth, the author rationalizes some of its elements, describing the most popular versions of the myth as an effect of rumours to not lose the coherency of the narration. Thus the Labyrinth was allegedly ordered by Minos because he desired to own a maze similar to those in Egypt. Still, it is said to be only a rumour: it was designed as a treasury or a prison for the white bull of Poseidon. Glaucus, the king’s son, got lost there. The statue of the City Guard – a huge man with a bull’s head – built by Daedalus on Minos’ order, became the source of the legend of an immortal bull of Poseidon called Minotaur, who guarded the island. Since Athens were to pay Crete a tribute of young men, the fear and uncertainty felt by the hostages became the source of fantastic and exaggerated tales about the Minotaur.

The retelling of the myth does not end with Icarus’ death. Instead, the author extends the story to Daedalus’ stay in Sicily and, finally, to his journey to Sardinia. To end the main plot, the author adds two informative pages about Sardinia, archaeological sites of Nuragic civilisation, and artifacts discovered by Giovanni Lilliu (1914–2012), including bronze figurines of the Great Goddess and dolls with movable limbs designed by Daedalus. Żylińska concludes that because no wings have been ever excavated, it was probably Pasiphaë who provided Daedalus with a ship, although the legend took a different turn.

Further Reading

Jadwiga Żylińska— podróż sentymentalna, (accessed: September 6, 2021).

Marzec, Lucyna, Gatunki pisarstwa historycznego Jadwigi Żylińskiej (PhD thesis), Poznań: UAM, 2012.

Marzec, Lucyna, Jadwiga Żylińska— kapłanka, amazonka, czarownica, “Trzy kolory. Sabatnik boginiczno–femistyczny” 6, 2011, http://sabatnik.pl/articles. php?article_id=259 (currently inaccessible).

Marzec, Lucyna, Jadwiga Żylińska, (accessed: September 6, 2021).

Sucharski, Robert A., “Jadwiga Żylińska’s Fabulous Antiquity”, in Katarzyna Marciniak, ed., Our Mythical Childhood... The Classics and Literature for Children and Young Adults, Boston–Leiden: Brill, 2016, 120–126.