Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

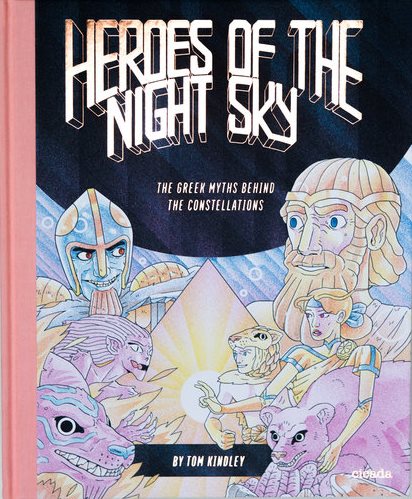

Tom Kindley, Heroes of the Night Sky. The Greek Myths Behind the Constellations. London: Cicada Books Ltd., 2016, 24 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Didactic fiction

Instructional and educational works

Myths

Picture books

Short stories

Target Audience

Young adults

Cover

Courtesy of Cicada Books Ltd., publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Sonya Nevin, University of Roehampton, sonya.nevin@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Dorota Mackenzie, University of Warsaw, dorota.mackenzie@gmail.com

Courtesy of the Author.

Tom Kindley

, b. 1990

(Author, Illustrator)

Tom Kindley (1990) is a British illustrator based in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. He studied at the Edinburgh College of Art before becoming a freelance illustrator and poster and zine creator. Many of his posters and zines contain detailed mythical features, including Rise of Achilles, which he describes as "A panorama describing the early life of the Greek hero Achilles, leading up to and including the beginning of the Trojan war"; Mother Medusa; and Mithras. He contributed to the graphic novel, IDP: 2043 (Freight Books, 2014).

Bio prepared by Sonya Nevin, University of Roehampton, sonya.nevin@roehampton.ac.uk

Summary

This is a collection of myths told for teenagers, with emphasis on stylised illustration, constellation name aetiologies, and some moral lessons. The myths included are:

- Ursa Major (The Great Bear)

- Pegasus

- Andromeda

- Hercules

- Lyre (The Lyre)

- Corona Borealis (Northern Crown)

- Orion and Scorpius

- Corvus (The Crow)

- Centaurus (The Centaur)

- Ophiucus (The Serpent Bearer)

Analysis

This is a highly illustrated collection, with a gatefold format. Each story is told on four pages; the first outlines the myth in narrative form on a plain background, with the diagram of the constellation as the only illustration. The following three pages relate the key points of the myth, with the fold-out format enabling the reader to see all three of the pages at once. The intricate page layout demonstrates the illustrator's strong roots in graphic novels, with the pages divided into a diverse selection of panels. These take a range of shapes and they vary in size from several on one page, to filling two or three of the illustrated pages. The three illustrated pages explain the connection between image and myth with short, boxed captions, which are also reminiscent of a graphic novel style. The illustrations are full-colour, sumptuously drawn and full of detail, energy, and emotion. The style of the illustrations is arguably slightly psychedelic, giving a somewhat space-age feel to the ancient mythic universe they depict.

The introduction explains that the constellations could be used for navigation, as a calendar and as a means of working out when to plant crops and when to harvest them and that the stories the Greeks projected onto them offered some explanation for the uncertainties of life.

Ursa Major is dominated by three images of deities in similar poses but carrying out very different functions. In the first, Artemis appears still, statuesque, receiving the worship of Calisto. Zeus pursues Calisto in small panels surrounding this image, helping to communicate the contrast between what should be happening (main image), and what is (border images). In the second major image, Artemis is in a similar pose, but she now looks dynamic, activated; she is furiously transforming Calisto into a bear. A huge crowd of Artemis' companions flow from the border of this image into the next, where they then surround Zeus and the bear. Zeus is standing in the position formerly adopted by Artemis; he is protecting the bear-Calisto from the companions, one of whom has shot the bear. This provides a visual indicator of how Zeus has interrupted the original arrangement of things, as well as the sense that he is protecting Calisto through "pity." Zeus and Calisto's sexual misdemeanour and her expulsion from her peers are expressed eloquently through only a few images.

Although the text in Andromeda refers to "Fearless Perseus" contrasted with "Beautiful Andromeda," the story-telling is unusual in combining an illustration of Andromeda chained with one of her freed and helping Perseus to kill the sea monster. This gives Andromeda much more agency and adds depth to her characterisation. The story ends with reference to them living Blessed by the gods for their courage. Traditionally, Andromeda is a princess of Ethiopia, but there is no mention or indication of Ethiopia in this version. There is strong indication of the influence of film and Northern European myth mixing with the classical. Medusa is depicted as a sea creature with a serpent tail, as in the 1981 film, Clash of the Titans, while the sea monster is named "Kraken" after a monster which originated in Northern European myth and which was connected to the Andromeda story in the above mentioned Clash of the Titans. A caption explains that Perseus got his equipment from the gods and he is depicted wearing winged boots, shield, and a helmet with an eye on it, and carrying a sickle, features which appear in traditional versions of his struggle with Medusa (on equipment coming from the gods, Hermes, the sickle; Athena, the mirror; nymphs, the winged sandals, bag, and cap of Hades, see e.g. Hesiod, Shield of Heracles, lines 216–236; Euripides, Electra, line 460; Apollodorus, Library, 2. 36 – 42; Pausanias, Guide to Greece 3. 17. 3).

The narrative page for Hercules provides a brief biography of the hero, while the illustration pages depict the defeat of the Nemean Lion, the fight with the Hydra, Hercules carrying the Erymanthian Boar and killing a Stymphalian bird, and Hercules dragging a chained Cerberus up from a flaming, hellish Underworld. Hercules appears beardless, arguably a form that is easier for teens to identify with.

Pegasus includes a depiction of a disappointed-looking Zeus casting down Bellerophon, whose "pride gets the better of him." Bellerophon's "arrogance" is contrasted with the "loyal service" Pegasus showed to Zeus. There are two fabulous images of a huge and scary Chimera, which has two front heads (lion and goat), two snake head tails, paws at the front and hooves at the back.

In Lyra (The Lyre), while the aetiology of the Lyre constellation is told, the more personal tragedy of Orpheus and Eurydice is the preeminent theme. Charon is depicted as a cloaked, bird-headed skeleton in a Hades full of skulls and skeleton soldiers. There is a large image of Cerberus, and a caption that Cerberus and Charon are both "charmed" by Orpheus' music. Hades sits on a stone throne stacked with skulls; he smiles because Even Hades is moved by [Orpheus'] beautiful music. A sequence depicts Orpheus and Eurydice's journey to the surface through a black tunnel; Orpheus looks back to Eurydice because he is full of joy to be near the surface. She is "lost to him forever." The final caption notes optimistically that Orpheus still makes music and Apollo placed the lyre among the stars, but the feel of the ending is dominated by a harrowing image of a desperate Orpheus separated from Eurydice, who is being enveloped by a crowd of skeleton warriors as Hades reaches out for her.

Corona Borealis relates the story of Theseus and the Minotaur with an unusual degree of emphasis on the happy ending for Ariadne and Dionysus, as led by the focus on the constellation. Theseus killing the Minotaur with Ariadne's help occupies the first picture page, Ariadne's sorrow and the arrival of Dionysus the second, and Dionysus with Ariadne forms the third page. The retelling of the myth on the introductory page emphasises Theseus' faithlessness towards Ariadne (he is quickly "tired" of her); it finishes with Dionysus overcome by happiness at his union with Ariadne and flinging their wedding crown into the sky. The final image of them depicts Dionysus showing Ariadne the crown constellation, while the caption notes that it will commemorate their love forever. (see esp. Ovid, Metamorphoses, 8.155–182,)

Orion and Scorpius offers sensitive context to Orion's fateful boast in which he wishes to impress Artemis. His boast – that he could kill anything – enrages Gaia, who sends a scorpion to challenge him. The narrative ends with emphasis on the Scorpion's constant connection to Orion in the sky, while the triptych finishes with an image of a distraught Artemis holding Orion's body; both versions suggest criticism of Apollo's jealous deception of his sister. Artemis is relatively passive in this retelling; the virgin goddess is said to be "smitten" with Orion and mistaken in killing him, creating a sorrowful tale (for Orion in antiquity, see Homer, Odyssey, 5.121–124; 11.572–575; Apollodorus, 1.4.3–5; Pausanias, 9.20.3).

Corvus (The Crow) carries a moral message against deception, as the eponymous crow is transformed for attempting to deceive Apollo. Apollo is depicted in two striking images glowing gold and emanating light.

Centaurus contains the tradition found in Pseudo-Apollodorus (Bibliotheca 2. 83–87), that Chiron transferred his immortality to Prometheus once Chiron was incurably injured. Chiron, the wise centaur is depicted wearing a long tunic, and Pholus, Hercules' centaur friend wears a kilt-like skirt. The clothing conceals the monstrous join between their humanoid and horse parts; the wild centaurs have no such cover and appear all the more savage for the contrast that their nakedness presents. Hercules appears as he did earlier; an earnest beardless youth.

The story of Asclepius concludes the collection. Apollo and Hades both look-on in interest, peering over the picture border to watch Asclepius restore a child to life. The book finishes on what feels like a fair compromise; Asclepius is killed but given eternal life as a constellation. Apollo's hand can be seen holding up the sun as a bright spot in an otherwise dark sky.

This is a dynamic collection of retellings that uses visual style to stress the other-worldliness of ancient myths, while this estrangement is balanced with attention to a wide variety of profound human emotions. In this sense, the book offers young readers fantasy and escapism coupled with an opportunity to explore varied difficult emotions and scenarios. The complex lay-out of the stories allows the reader to choose how they will engage with the book, perhaps changing the style of engagement with each visit, with options to focus on the narratives, images, text boxes, or a combination of all forms. The science-fiction influence within the ancient world illustrations makes the collection interestingly future-orientated, while still embracing the past. Young people enjoying this collection have the opportunity to learn the stories of the constellations with a wealth of further ideas and concepts wrapped up with them.

Further Reading

Evans, J., The History and Practice of Ancient Astronomy, London: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Kummerling-Meibauer, Bettina, "Orpheus and Eurydice: Reception of a Classical Myth in International Children’s Literature", in Katarzyna Marciniak, ed. Our Mythical Childhood... The Classics and Literature for Children and Young Adults, Leiden: Brill, 2015.

Lorimer, H. L., "Stars and Constellations in Homer and Hesiod", The Annual of the British School at Athens 46 (1951): 86–101.

MacGillivray, Alexander, "The Astral Labyrinth at Knossos", British School at Athens Studies 12, KNOSSOS: PALACE, CITY, STATE, 2004, 329–338.

Maurice, Lisa, "From Chiron to Foaly: The Centaur in Classical Mythology and Fantasy Literature", in Lisa Maurice ed., The Reception of Ancient Greece and Rome in Children’s Literature. Heroes and Eagles, Leiden: Brill, 2015.

Roberts, Deborah H., "The Metamorphosis of Ovid in Retellings of Myth for Children", in Lisa Maurice, ed., The Reception of Ancient Greece and Rome in Children’s Literature. Heroes and Eagles, Leiden: Brill, 2015.

Stafford, Emma, Herakles. London: Routledge, 2012.

Webster, T. B. L., "The Myth of Ariadne from Homer to Catullus", Greece & Rome 13.1 (1966): 22–31.