Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Geraldine McCaughrean, Theseus. Chicago: Cricket books Chicago (with arrangement with Oxford University Press), 2003, pp. 102.

ISBN

Genre

Action and adventure fiction

Adaptations

Didactic fiction

Target Audience

Young adults (10 and up years)

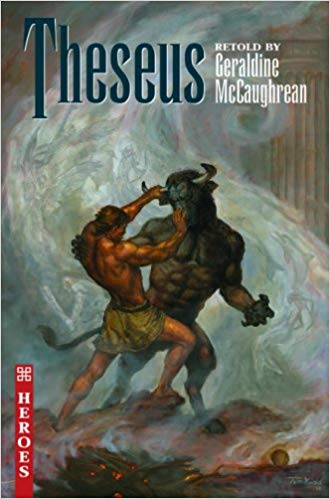

Cover

Courtesy of Cricket Media.

Author of the Entry:

Ayelet Peer, Bar-Ilan University, ayelet.peer@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Courtesy of the Author.

Geraldine McCaughrean

, b. 1951

(Author)

McCaughrean is a British novelist who currently resides in Berkshire, England. She is a prolific writer, who wrote of over 170 books – mostly children’s books but also several historical novels for adults. She won numerous awards for her books. In addition she also wrote a play for the radio and stage-plays. She grew up in North London and studied at Christ Church College of Education, Canterbury.

McCaughrean was the only author who won the Whitbread Children’s Book Award three times; she won it for her children’s novels: A Little Lower than the Angels (1987), Gold Dust (1993) and Not the End of the World (2004).

Sources:

Official website (accessed: May 28, 2018).

Profile at the literature.britishcouncil.org (accessed: May 28, 2018).

Bio prepared by Ayelet Peer, Bar-Ilan University, ayelet.peer@gmail.com

Questionnaire

1. What drew you to writing / working with Classical Antiquity and what challenges did you face in selecting, representing, or adapting particular myths or stories?

I loved the Classic myths as a child, though the books were a bit dull, illustrated with Greek statuary or Roman urns. There was a resurgence of interest in publishing them for children at the time I was newly surfacing as an author, so naturally I leapt at the chance to retell them. The illustrations were a lot better this time round.

The choosing of stories is largely guided by which are best known and (especially nowadays) those which feature on the National Curriculum. That, in turn, is largely guided by which are not too salacious or amoral. The Greek myths win out every time in terms of what the publishers choose to publish and what the schools choose to teach. I am particularly fond, however, of the Epic of Gilgamesh and like to harp on about that whenever I get the chance.

2. Why do you think classical / ancient myths, history, and literature continue to resonate with young audiences?

It is one of the few chances children get to be treated like adults. Since the stories were originally told to a diverse audience, and they are distinctly not "kiddies’ stories", young readers/listeners are for once given a glimpse of adults (and gods) behaving badly, death, battle, love, fate and so on, as well as identifying with heroes, superhuman beings and adventurers, all in a heady, sun-and-sea setting. Other "educational" retellings I am asked to write (such as fairy tales) come with a prohibition list of no-nos – knives, soldiers, witches, religion, war, sex, alcohol... All of that goes out of the window with Myth because (of course) such things are the substance of Myth. They are also the substance of Life and there are important things to be said about them – passed on from one generation to the next by means of story.

The sheer strangeness of times-long-gone are intriguing to children. I have never seen the need for "contemporary relevance" when it comes to entrancing children with Story. They can, after all, dart imaginatively through Time and Space with more ease than adults, and relish unquestioningly the most mind-boggling fantasy without turning a hair.

3. Do you have a background in classical education (Latin or Greek at school or classes at the University?) What sources are you using? Scholarly work? Wikipedia? Are there any books that made an impact on you in this respect?

I’m no classicist. I did do Latin to O-level at school, but none of it has stuck unless residually in my spelling. I wrote a collection of 101 Myths and Legends from Round the World which helped me see "Classical" myth in its global context, and how its influence travelled far farther afield than the Greeks themselves ever did.

For sources, I don’t go to other children’s versions, for obvious reasons, but to Robert Graves or adult encyclopaedias of Mythology or Penguin versions of the epics.

4. Did you think about how Classical Antiquity would translate for young readers?

The arrant misogyny and gynophobia of the ancient Greeks are an undoubted problem. Almost every monster is female, almost every female is scheming or dangerous, a snake under her skirts, or only there to be conquered and bedded. Heroes like Hercules get through droves of women – and then there are his dubious shield-bearing beloved boys...

I do an exercise in schools whereby Perseus goes off to kill Medusa clad in all the language of heroism and admirable virtues... and then, as the kid raises his sword to strike, I point out that, by the way, he has abandoned his mother in her hour of need because he fell for a flattering trick and boasted he could kill the gorgon, so has flown off to kill a woman he has never met and knows nothing about – a woman who was transformed and deformed through no fault of her own, and – ooo – who happens to be pregnant with twins when Perseus slashes her head off her shoulders. It’s a nice exercise in "viewpoint". ... But of course in retelling the myth in writing I can’t do that. I have to be true to the stories I loved myself as a child, and trust to the appeal that has kept them alive and popular for thousands of years.

5. Writers are often more "faithful" to originals in adapting its spirit rather than being tied down at the level of detail – is this something you thought about when writing your stories?

I do feel quite strongly that the tradition – the etiquette, if you like – of storytelling is that while the storyteller has charge of the story it is theirs to do with as they like. Which source should I go back to for perfect accuracy, after all? The oldest? The first-time told? Hardly. Where a culture’s religion is involved, then it’s wrong to mess with a mythic story. But there can be very few Olympian-worshippers these days I could offend by missing out a detail or two. The patchwork-quilt way that the canon of Greek myth grew gives rise to lots of anomalies anyway – e.g. Hercules doing his deal with Atlas at least two generations after Perseus turned Atlas into a mountain.

All the same... when TV series or novelizations credit the wrong heroes with the wrong adventures, I go ape!

As for details... Those three drops of olive oil that Psyche spills on to Cupid’s shirt as she takes a peek at him after dark... when you see how they survived over the centuries to turn up as three drops of blubber oil in a telling of East of the Sun and West of the Moon... well it makes you believe that myths have DNA that will survive somehow despite the worst time and interfering storytellers can do to them. Details like that are truly precious.

Prepared by Ayelet Peer, Bar-Ilan University, ayelet.peer@gmail.com

Summary

The book unfolds the adventurous life of the Athenian hero Theseus from his birth to his old age. We learn of his different exploits and acts of bravery (slaying giants, fighting the Minotaur), as well as his mistakes and flawed relationship with others (the Amazon queen Hippolyta, his son). Through the story of Theseus expedition to Crete, to fight the Minotaur, two more characters are introduced, Daedalus and Icarus. Their story, especially their fatal flight is interwoven with Theseus’ fight with the Minotaur.

Analysis

What makes a hero? This is the question that forms the heart of this book, which is a part of a “heroes” series. The prevailing theme of this book is the examination of Theseus’ status as a hero and its broader meaning. Why is Theseus a hero? Throughout the book, it seems as if the author is questioning Theseus’ heroism, especially due to his excessive pride and poor treatment of others, especially women. Theseus is described as hurting, even deceiving Ariadne, whom he did not really love and intended to marry. He badly hurts the noble Hippolyta and eventually pays for this mistreatment by the cruel act of Phaedra, which makes him order the killing of his son. When McCaughrean describes his various acts, she emphasizes how he waited for divine approval and she occasionally mentions his pride in the story. While this is a book for adolescents, the author nonetheless does not try to gloss over all of Theseus’ acts. On the contrary, she creates a stimulating and subtle discussion about pride, character and heroism. She does so by showing Theseus’ actions not as motivated by the need to defend others, but as means to elevate himself. The preface of the story also alludes to the author’s intent.

Although Theseus is a mythical hero, it is questionable as to whether he can be considered heroic in a modern sense from his actions. He slays giants in order to win fame, rather than to help the common good, as the author clearly emphasizes. Although this was a common trait for mythological heroes, the author chooses to emphasize Theseus’ vanity. In fact, the readers might find that the Theseus who emerges from the story is not a sympathetic character at all. While younger readers will be attracted by his adventures and his combat against various creatures more attentive readers might possibly question his motive and overall behaviour. The author might be trying to present a conflict between what was considered heroic and what is the modern assumption of one. It is clear from the story that she deems character more important than physical prowess.

At a preface to the story, the author inserts a paragraph that provides a caveat to the idea of Theseus as a hero: “Congratulations. You must be proud of yourself. Yes, surely! Looking back, everyone can think of things they have achieved…actions to be proud of…look at Theseus...but Theseus was a hero, after all, and a hero needs a broader gangway through the world. People should step back and let him pass...and yet…a hero should give credit where it’s due and preserve a kind of modesty. Otherwise he…be cursed by the gods for the sin of pride.” While this note is not a part of the actual narrative, it nonetheless sums up the author’s main moral of the story. It refers quite cynically to the conceit of heroes (people should let them pass), and it also hits at Theseus’s sin of pride, which will become the main theme of the story.

The author tells the readers that they may also consider themselves heroes, based on their actions, but she also reminds them that not all actions are perfect and some are lamentable, even those of a renowned hero like Theseus. This teaches the readers that they should not be blinded by titles; being called a “hero”, does not entitle a person to act haughtily. Everyone can be a hero, but it is more important to be gracious and modest.

We first learn of Theseus’ pride form his mother, who complains to Hercules “Theseus! How often must I tell you? Don’t brag. I’m sorry Hercules, but there’s a streak of pride in the boy that the gods would frown on if they saw it.” (p. 12). Aethra’s words are a hidden prophecy which continues throughout Theseus’s life. For this reason, the author emphasizes on each occasions that Theseus performs some act of conventional bravery (fighting a dangerous enemy), he immediately seeks recognition and applause: “when he saw what he had done and how easily he had done it, Theseus gave a great leap in the air and spread his hands toward heaven as if to say, ‘Did you see? Were you watching?’” (p. 24). Pride is Theseus’ constant companion, even in his encounter with King Minos (p. 57). This sentiment never leaves Theseus and only increases as he grows more successful.

A powerful example of the destructive force of pride is presented in the story of Daedalus and Icarus. Icarus, who likened himself to the god Hermes, soon fell from the sky. While Theseus and Icarus are very distinct, they both share the same flaw. Icarus’ end is a foretelling of a similar end awaiting Theseus; he will also metaphorically fall form the sky, from the highest position to nothingness.

Even as an old man, Theseus refuses to acknowledge reality; “In his pride, Theseus did not notice that his own bright hair was graying…and that heroes, when there are no monsters left to fight, grow old like ordinary men.” (p. 86). Here again the author pokes the hot air balloon of heroism, by making the heroism hollow and completely reliant on others, namely monsters. Heroes are ordinary men who simply faced unordinary circumstances and triumphed, but they are not superior to others. In the end, proud Theseus is depicted pitifully, sitting alone on a beach beside a fire, while his own pride consumes him. Theseus does not die in the story, yet he is just sitting pathetically alone on the beach: “sailors passing by in ships sometimes saw him sitting beside a fire on the beach and hailed him and waved greetings. But Theseus was far too proud to wave back.” (p. 102). His was a pathetic end, unworthy of a true hero, but it was the ultimate reward for his conceit. Theseus distances himself from human society and prefers his loneliness.

Thus this book, rather than applauding the adventures of a mythical hero, has a pedagogical mission to emphasize the flawed character of Theseus, and make the readers think more deeply about his acts and their consequences, rather than simply focusing on action and battles. Being a hero is not as glorious as it may seem, and what counts at the end, is not how many monsters you have slayed, but how you treated the people closest to you in your life.