Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Joan D. Vinge, The Random House Book of Greek Myths. New York and Toronto: Random House Inc., 1999, 156 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Adaptations

Fiction

Illustrated works

Myths

Target Audience

Children

Cover

We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover.

Author of the Entry:

Robin Diver, University of Birmingham, robin.diver@hotmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

Oren Sherman (Illustrator)

Oren Sherman is an American artist, illustrator and university professor. He is an alumnus and lecturer at Rhode Island School of Design, where he specialises in teaching colour theory, storytelling, design, entrepreneurship and pattern. As an artist, he specialises in brand identity and has worked with a diverse range of clients, including Pepsi, Disney, the US Postal Service, Hermes and the US Mint. He draws inspiration from American poster artists of the 1920s and 1940s. The back cover to this book (The Random House Book of Greek Myths) claims of Sherman that, "he brings his lifelong interest in and passion for Greek myths to this collection, his first foray into illustrating books for young people."

Sources:

Back cover of The Random House Book of Greek Myths

Official website (accessed: March 6, 2019)

Profile at risd.edu (accessed: March 6, 2019)

Bio prepared by Robin Diver, University of Birmingham, RSD253@student.bham.ac.uk

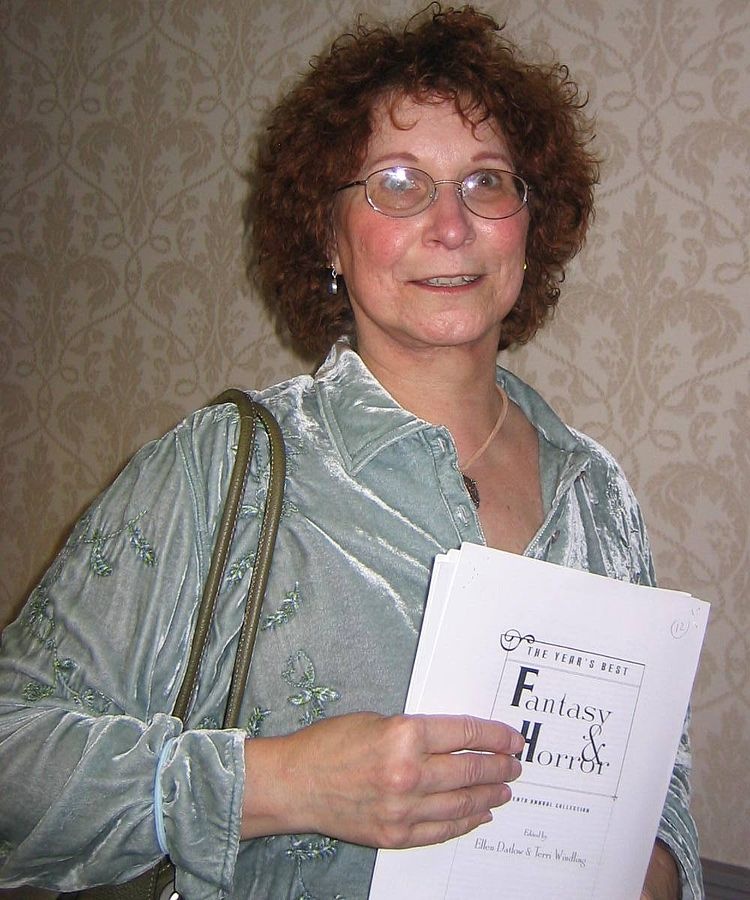

Joan D. Vinge by Ellen. Retrieved from flickr.com, licensed under CC BY 2.0(accessed: December 28, 2021).

Joan D. Vinge

, b. 1948

(Author)

Joan Vinge (b. Baltimore 1948 Joan Carol Dennison) is an American author and dollmaker famous for her science fiction works. She studied anthropology at San Diego State University, after changing from an art major. Vinge is married to James Frenkel, a science fiction editor with whom she has two children. Previously, she was married to another science fiction author, Vernor Vinge. She currently lives in Arizona.

Her best-known work, The Snow Queen, is a science fiction retelling of the famous fairy tale, with influence from the theory of the great goddess popular in the 1970s, and ideas of sacrificial ancient kings. The names of several ancient goddesses appear in the novel, as well as the theme of Sibyls.

Sources:

Back cover of The Random House Book of Greek Myths.

Profile at en.wikipedia.org (accessed: March 6, 2019).

Bio prepared by Robin Diver, University of Birmingham, RSD253@student.bham.ac.uk

Summary

This is an anthology book for children which presents the key figures and stories from classical mythology. The retellings are generally fairly standard versions of the myths, with some unusual details included from ancient versions, such as Medea’s resolution to kill her children (although this is not carried out). This is a rare version in which Pandora has a jar not a box. The chapters are lightly illustrated with intense, bold and dark colour illustrations drawing influence from Greek vase art. The first chapter, Mount Olympus, introduces the gods in detail and tells the best-known stories about them to give context for the later chapters. The Afterword talks about Rome and the repurposing of the gods as Roman deities.

- Introduction.

- Mount Olympus – Includes mini sub-chapters on each of the gods.

- Minor Gods and Goddesses.

- The First Human Beings.

- Pandora’s Jar.

- The Great Flood.

- Perseus and Medusa.

- Phaethon.

- Pegasus and Bellerophon.

- Orpheus and Eurydice.

- Jason and the Golden Fleece.

- Atalanta.

- Eros and Psyche.

- Theseus and the Minotaur.

- Daedalus and Icarus.

- Echo and Narcissus.

- Hercules.

- Afterword.

- Index.

Analysis

This anthology begins with the assertion that the Greeks created myths to explain “things [which] happened to people that were beyond anyone’s control.” (p. 10). Since Vinge includes unexpected love, death and good luck in this in addition to weather and natural events, her explanation for mythology is essentially an expansion on the argument in other anthologies such as Heather Alexander (2011) that myth is an explanation for natural phenomena. The introduction somewhat Christianises the function of the Greek gods – “the Greeks believed their gods had created the heavens and the earth” (p. 10). It also attempts to set them apart from other mythologies. In reality, the Greeks do not appear to have been unique in imagining that “their gods had lives and feelings like their own.” (p. 10). Vinge also echoes other anthologies in asserting in her introduction that the myths are still told today “because they are such good stories.” (p. 10).

Vinge draws on the idea of the great goddess popularised by authors such as Robert Graves and Merlin Stone in the twentieth century. This is the belief, not well regarded within modern day academia, that at some point religion was matriarchal and revolved around a mother goddess who was eventually displaced by a series of patriarchal invasions. This may have been a popular theory at the time Vinge would have completed her anthropology degree, and its influence can also clearly be seen on her science fiction writing. In her introduction to the anthology, Vinge states “Some experts on mythology believe that in the original version of the myths, goddesses ruled the heavens and earth.” (p. 11).

Vinge also attempts to apply the goddess theory to the goddess Amphitrite’s story: “Zeus made the sea goddess Amphitrite marry Poseidon….Poseidon got to take over all of Amphitrite’s titles and powers; he now commanded the waters and all the creatures that lived in the oceans.” (p. 19). The influence of feminist reception and feminist responses more generally can also be seen in the anthology; for example, Artemis and Atalanta both place great importance on their independence from men in a way reminiscent of modern feminist dialogues. Vinge complains that Zeus and his brothers treat their sisters unfairly by not including them in the draw for the heavens, sea and underworld (p. 17), a criticism that would be repeated in Donna Jo Napoli’s 2011 children’s anthology.

There are further signs of influence from Robert Graves and other authors, aside from the use of the goddess theory. For example, Vinge says Zeus justified his multiple other relationships and children by telling Hera “he was doing it for the sake of humankind, because his sons from these marriages would be great heroes. He said his marriage to her was the only real one, because all his mortal wives would someday grow old and die. Hera would be his young and beautiful queen forever.” (p. 18). Graves in his 1960 children’s anthology stated that Hera “disliked being Zeus’s wife, because he was frequently marrying mortal women and saying, with a sneer, that these marriages did not count – his brides would soon grow ugly and die; but she was his Queen, and perpetually young and beautiful.” (p. 4). In the D’Aulaires’ children’s anthology (1962), Zeus thinks to himself that “All his children would inherit some of his greatness and become great heroes and rulers” and therefore Hera is wrong to be angry about his other children (p. 24). We can therefore see how Vinge’s anthology draws on and is in dialogue with earlier children’s literary receptions. The description of the throne of each member of the Olympian council is also reminiscent of Graves’ children’s anthology.

Vinge is, in general, unusually sympathetic to Hera. She makes the point that Hera punishes Zeus’ “other women” because she is unable to punish Zeus (“Zeus always had his lightning bolts handy”, p. 18). Whilst this might seem obvious, it is a point missed surprisingly frequently in reception. For example, Jean Shinoda Bolen’s 1984 attempt to reclaim Greek goddesses for feminist purposes, Goddesses in Everywoman, claims “Hera’s rage was not aimed at her unfaithful husband; rather, it was directed at ‘the other woman’ (who more often than not had been seduced, raped or deceived by Zeus), at children conceived by Zeus, or at innocent bystanders.” (p. 140). Bolen advises women that they may express a “Hera archetype” and have an unfair urge to punish other people over the actions of a substandard or straying husband, not the husband himself (p. 146). This analysis misses that Hera in ancient mythology is in no position to punish her husband.

Hera’s kindness is emphasised in the story in which Zeus transforms into a bird to woo her – “She felt sorry for the poor bird and hugged it tenderly.” (p. 18). She even eventually feels guilty about tormenting Leto. Zeus himself is portrayed as a flawed character – something that would become the norm in twenty-first century anthologies. “Zeus was the strongest of the gods and usually the bravest. He was not always the wisest, however. He had a bad temper, and could be selfish or impulsive…. Although he was the king of the gods, even mortals sometimes laughed at his follies (but not too loudly).” (p. 17).

Generally, this anthology follows the trend towards a sympathetic depiction of Hades that seems to have become popular in the 1990’s and has largely continued to the present day. Whilst Vinge does not go as far as, for example, Geraldine McCaughrean’s anthology of 1992 in encouraging the child reader to feel sympathy for Hades, she does emphasise the grimness and loneliness of Hades’ home. As in many children’s retellings, Hades thinks to himself how Persephone’s beauty will “brighten his cold, dark palace” (p. 23). Zeus initially refuses Demeter’s request for Persephone’s return because he “wanted his grim brother to be happy for once” (p. 23).

Rather than showing sexualised brutality, as in illustrations in other anthologies, Sherman depicts Persephone’s abduction in a manner evocative of literal death. Hades is a stiff, stone-coloured figure without hair. Persephone lies draped over his shoulder, eyes closed, head flung back and one arm reaching upwards towards the world of light as she descends into the pit. The reaching arm appears almost suggestive of rigor mortis.

Like many recent children’s anthologies, Vinge displays discomfort with the presence of the hunting of animals in Greek mythology. For example, Artemis’ “arrows were magic and caused no pain, for Artemis did not like to bring needless suffering to any creature she hunted.” (p. 30).

The front cover depicts Bellerophon riding Pegasus over an orange and blue mountain range. This is typical of anthologies published around this time, which often show Pegasus and Bellerophon on a blue background. For example, the cover to Heather Amery’s anthology of the same year places Bellerophon and Pegasus on a blue square of sky as they ride over the sea, and Lucy Coats’ 2002 anthology also shows Bellerophon and Pegasus flying over the sea on a blue and orange background. The figures and background colours on Sherman’s front cover, therefore, were apparently highly reflective of what children’s publishers felt would sell at the time.