Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

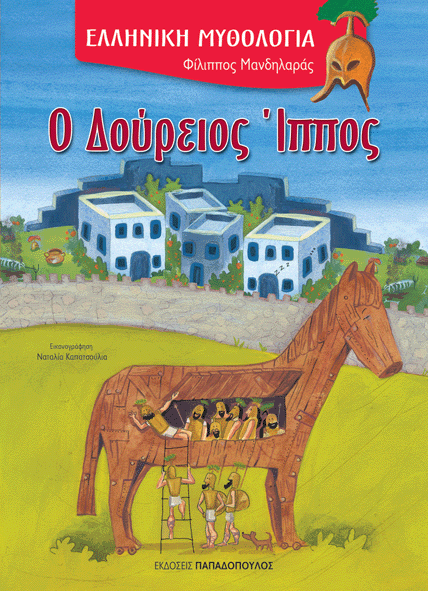

Filippos Mandilaras, Ο δούρειος ίππος [O doúreios íppos], Greek Mythology [Ελληνική Μυθολογία (Ellīnikī́ Mythología)]. Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2012, 16 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Illustrated works

Target Audience

Children (Children aged 4+)

Cover

Courtesy of the Publisher. Retrieved from epbooks.gr (accessed: July 5, 2022).

Author of the Entry:

Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

Natalia Kapatsoulia (Illustrator)

Natalia Kapatsoulia studied French Literature in Athens, and she worked as a language tutor before embarking on a career as a full-time illustrator of children’s books. Kapatsoulia has authored one picture book Η Μαμά πετάει [Mom Wants to Fly], which has been translated into Spanish Mamá quiere volar. Kapatsoulia, who now lives on the island of Kefalonia, Greece, has collaborated with Filippos Mandilaras on multiple book projects.

Sources:

Official website (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Profile at the epbooks.gr (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Filippos Mandilaras

, b. 1965

(Author)

Filippos Mandilaras is a prolific and well-known writer of children’s illustrated books and of young adults’ novels. Mandilaras studied French Literature in Sorbonne, Paris. His latest novel, which was published in May 2016, is entitled Υπέροχος Κόσμος [Wonderful World], and it recounts the story of teenage life in a deprived Athenian district. With his illustrated books, Mandilaras aims to encourage parents and teachers to improvise by adding words when reading stories to children. Mandilaras is interested in the anthropology of extraordinary creatures and his forthcoming work is about Modern Greek Mythologies.

Sources:

In Greek:

Profile on EP Books' website (accessed: June 27, 2018).

i-read.i-teen.gr (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Public Blog, published 15 September 2015 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Press Publica, published 28 January 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Linkedin.com, published published 6 May 2016 (accessed: February 6, 2019).

In English:

Amazon.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

On Mandoulides' website, published 7 March 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

In German:

literaturfestival.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Adaptations

The book is an adaptation of the book published in 2009 within the series My First Mythology:

Filippos Mandilaras, Ο δούρειος ίππος [O doúreios íppos], Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2009, 36 pp.

Demo of 9 pages available at epbooks.gr (accessed: October 13, 2021).

Summary

After Achilles’ death, morale was low in the Achaean army. Odysseus came up with a cunning plan for capturing Troy. Agamemnon agreed to the plan “with a heavy heart”, because the operation was risky. Epeius was tasked with constructing a large wooden horse with a hollow stomach to accommodate one thousand soldiers. Once completed, an inscription was carved on the horse’s head reading “a present by the Achaeans to Athena”. Next, the Achaeans burnt their camp and sailed away. Only the bravest of the Achaeans stayed behind, hidden inside the horse’s stomach.

At daybreak, the Trojans thought that the Achaeans had left. They saw the wooden horse. An Achaean soldier, as instructed by Odysseus, confirmed to the Trojans that the horse was a present. The Trojans believed the soldier and pulled the horse to the sanctuary on their acropolis. Cassandra, Priam’s daughter, advised them to burn the horse, but people did not listen to her. Laocoon, the priest of Apollo, warned the Trojans as follows: “be afraid of the Achaeans, even if they carry presents”. Two snakes emerged from the sea and attacked Laocoon, and he perished instantly. The Trojans celebrated the end of the war with dancing, singing, and drinking by the fire. When the celebrations were over and night came, the Achaeans got out of the horse and signalled at their fellow soldiers in the ships, which were hidden away. Thousands of Achaeans arrived. Troy was sacked and burnt. Then, the Achaeans ran away, being afraid of the gods’ punishment.

Analysis

The book adapts the well-known myth about the fall of Troy. Although Homer does not talk about the Trojan Horse in the Iliad, he seems to be aware of its legend. Here, the narrative begins with the death of Achilles, as covered in Achilles and Hector (my translation), another book by the same author and illustrator.* By contrast with that book, here we read about war tactics, which include deceit, rather than heroism in the battlefield. Odysseus’ resourcefulness is diametrically different from Achilles’ eagerness to exhibit martial excellence. The extreme emotions that drive Achilles’ anger and thirst for revenge do not play a role in how Odysseus acts. Rather, Odysseus is portrayed as a logical thinker who takes a step-by-step approach and implements his plan successfully.

Odysseus is clever and finds a way forward for a demoralised army that wishes to return home after ten years of fighting. Yet, he involves others and does proceed on his own. He solicits Agamemnon’s support. It is unclear from the ensuing pages whether or not Odysseus himself oversees the construction of the horse. Mandilaras uses verbs in the plural, e.g., “they allocate” and “they carved” (my translation, «αναθέτουν» and «σκάλισαν» in Greek). These verbs may refer either to Odysseus and Agamemnon acting together or to the Achaeans more generally.

An oblique reference to team work is also made in how the hidden soldiers need to behave for Odysseus’ plan to succeed. Inside the horse’s stomach they have to endure, “without water, without bread, without talking” (my translation, «δίχως νερό, δίχως ψωμί, δίχως μιλιά» in Greek). Once they step out, when everyone at Troy is asleep, the soldiers need to walk “like cats” (my translation, «σαν γάτες» in Greek). The colloquial language makes the story accessible to young children. More importantly perhaps, the collective action can be performed for play and educational purposes. Groups of children at kindergarten may wish to imitate the soldiers’ cat walking.

The construction of a wooden horse, furthermore, may inspire children to engage in craftworks. Indeed, Kapatsoulia’s illustration of Epeius’ workshop includes images of wooden toys, two rabbits and a bird. Children may think that the Trojan Horse was yet another toy, and not a war machine. In Classical art, too, the Horse is depicted as a normal horse, and not as a complex and massive device that could accommodate one thousand soldiers.** We read that the craftsman Epeius worked hard with tree trunks and planks. Teachers may explain to young children that the name ‘Epeios’ means ‘horse-man’ in Greek. The craftsman was well-suited for this creation. Whereas in the Iliad, a person with this name is mentioned as a boxer (Hom. Il. 23.689-91), in the Odyssey, Epeios is credited with building a horse of wood with the help of Athena (Hom. Od. 8.493ff). (Athena is not mentioned here.)

Odysseus’ deceitful plan works. The Achaeans destroy the city. The book closes, however, with a warning, and not a celebration of Odysseus’ ingenuity. Kapatsoulia’s illustration shows a grumpy soldier at the seaside holding a brush and sweeping helmets, presumably of fallen Trojans. The Achaeans seem to have forgotten, we are told, that whoever is disrespectful to human life will meet calamities in the near future. We lose sight of the Trojan Horse, which is not depicted in the last pages. Readers may be justified in thinking that the wooden horse burnt down when the city surrendered to flames. Children might find the loss of a toy-looking animal difficult to digest. War is to be understood as a terrible catastrophe that entails the destruction of both animate and inanimate entities. Evidently, Mandilaras and Kapatsoulia offer children and adult readers a didactic story with messages that reach beyond the realm of ancient myth.

* epbooks.gr (accessed: March 1, 2019).

** See Sparkes, B. A., "The Trojan Horse in Classical Art", Greece & Rome 18.1 (1971): 54–70 (accessed: March 1, 2019).

Addenda

Information about the book. Soft bound.