Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

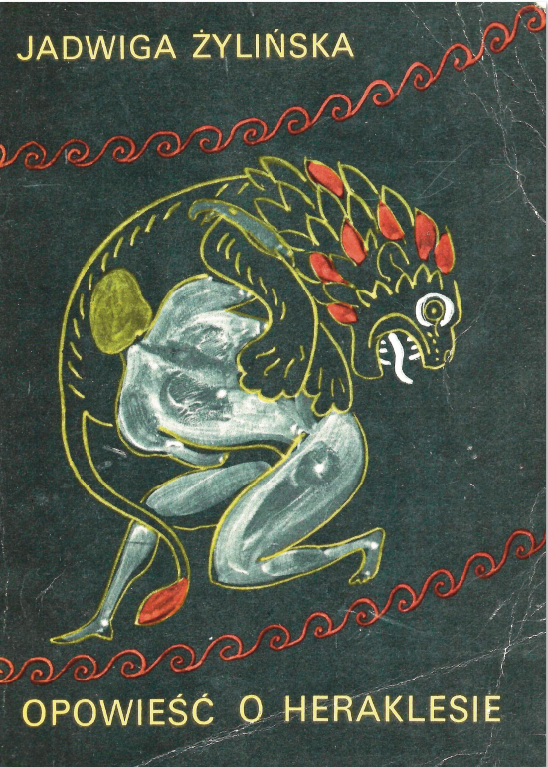

Jadwiga Żylińska, Opowieść o Heraklesie. Warszawa: Biuro Wydawniczo-Propagandowe RSW „Prasa–Książka–Ruch”, 1973, 85 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Adaptations

Myths

Target Audience

Children

Cover

The publisher of the text closed down in 1990 leaving no known successors, and we were unable to determine if there are any copyright holders. Including the cover in our database meets all fair use requirements, still, we invite the users to share with us any information they may have about copyrights to the posted materials.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Adam Ciołek, University of Warsaw, adamciolek@student.uw.edu.pl

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

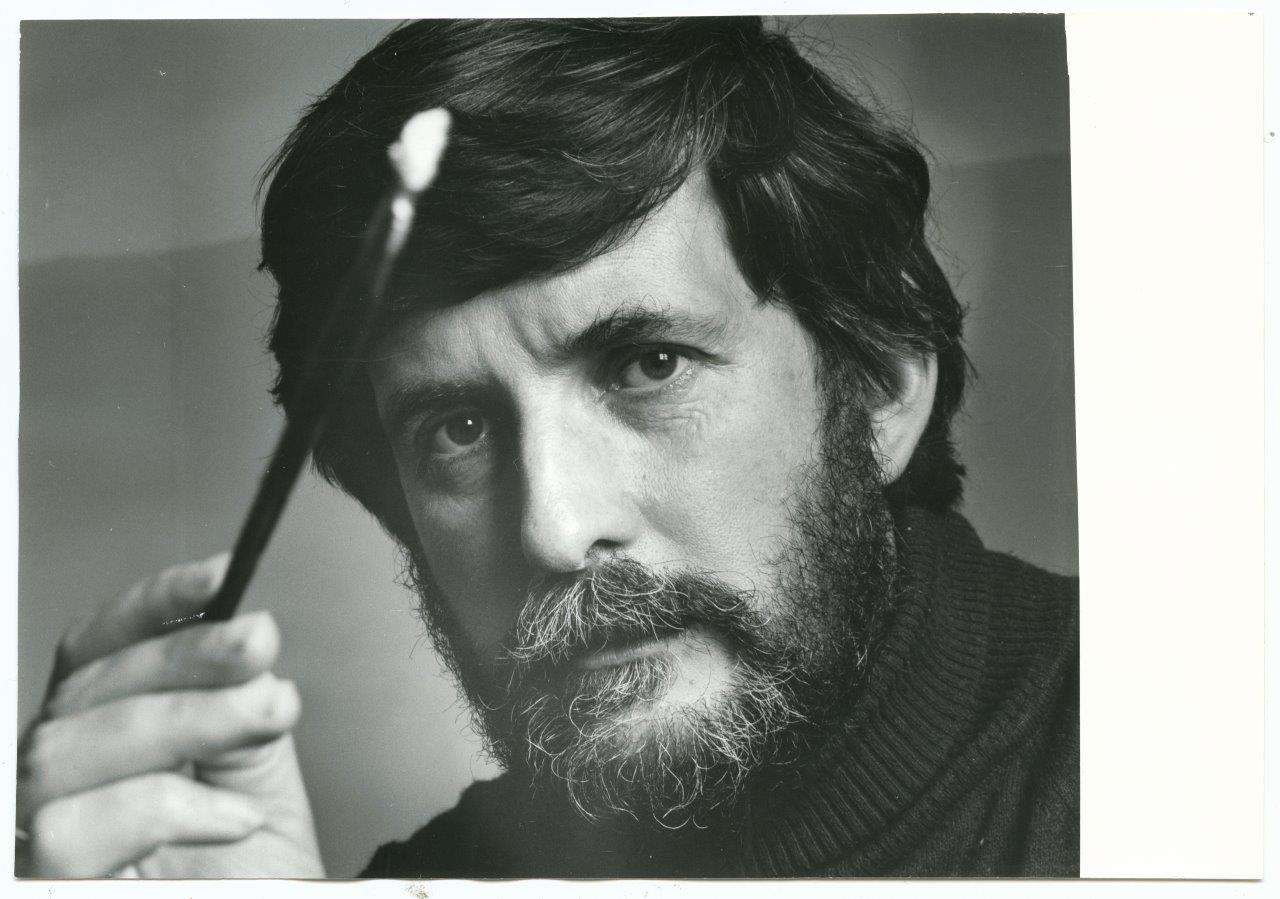

Courtesy of Barbara Towpik-Roszkiewicz, daughter of the artist.

Janusz Towpik

, 1934 - 1981

(Illustrator)

Janusz Towpik (1934–1981), originally from Cieszyn, was an architect with a diploma from the Warsaw University of Technology [Politechnika Warszawska] (1959). He also studied graphic design at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw [Akademia Sztuk Pięknych] and became a graphic designer and an illustrator. He designed postcards, stamps, matchbox labels, ex libris, logotypes, tapestries and intarsias.

Towpik illustrated children’s books, textbooks, fairy tales, and other stories to be viewed with a projector, nature atlases, popular science books, especially those about animals, and produced zoological tables for the PWN Encyclopaedia. In addition, he taught drawing at the Faculty of Architecture of the Warsaw University of Technology and conducted an arts club for children at the Warsaw Zoo.

Selected publications illustrated by Janusz Towpik, examples of his works, awards and exhibitions can be viewed online here and here (accessed: September 9, 2021).

Sources:

janusztowpik.pl (accessed: September 9, 2021),

"Janusz Towpik", at Artinfo.pl (accessed: September 9, 2021),

"Janusz Towpik. Natura i Fantazja", at ownetic.com (accessed: September 9, 2021),

"Janusz Towpik – Czarodziej Natury", at muzeum.edu.pl (accessed: September 9, 2021),

Gieżyński, Stanisław, Zwierzęta małe i duże, at Weranda.pl (accessed: September 9, 2021),

Towpik-Roszkiewicz, Barbara, Janusz Towpik, at Legendy Polskiego Jeździectwa website (accessed: September 9, 2021).

Bio prepared by Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

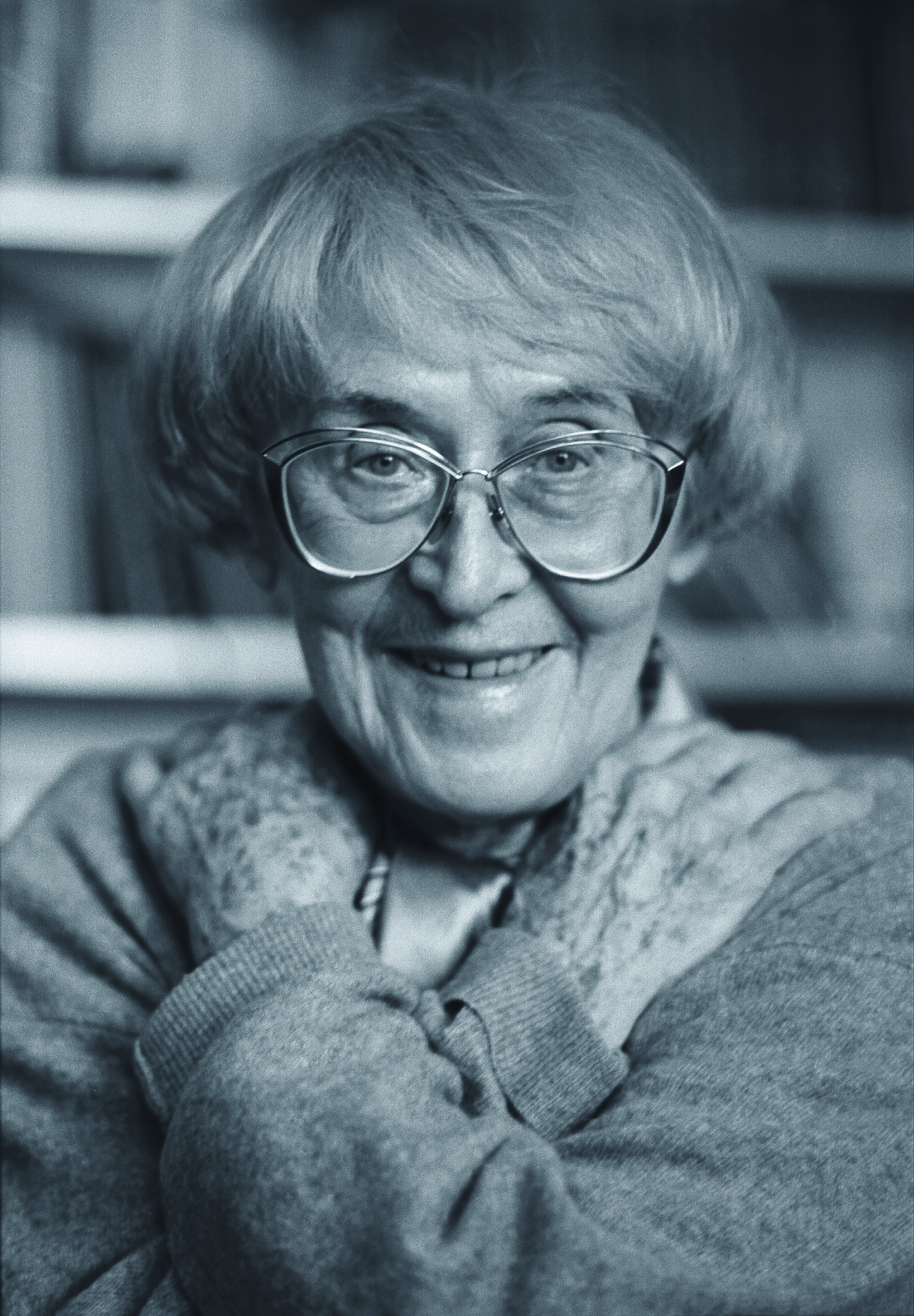

Photograph courtesy of its Author, Elżbieta Lempp.

Jadwiga Żylińska

, 1910 - 2009

(Author)

Born in Wrocław, lived in southern Wielkopolska [Greater Poland] (Ostrzeszów and Ostrów Wielkopolski), which influenced her later life. Graduated in English philology from the University of Poznań. Proficient in Latin, ancient Greek, English, and French. For many years worked for the Polish Radio. Prose writer, essayist, author of screenplays, radio dramas, historical novels, and books for children and young readers. Well known as an author of historical novels written from a woman’s point of view (the most important among these is a 2-volume novel Złota włócznia [The Golden Spear], 1961–1964). She made her debut in 1931 with a story for children Królewicz grajek [The Prince Piper] published in a periodical (still under her maiden name Michalska). Since 1964 member of the Polish PEN Club, in 1993 received the Polish PEN Club prize for lifetime achievement as a prose writer. Decorated with the Knight’s Cross of Polonia Restituta for outstanding achievements for Polish culture. Some of her books were translated into German and Russian. She is the author of a cycle Oto minojska baśń Krety [Here is the Minoan Tale of Crete], 1986, parts of which were also published separately.

Source:

Żylińska Jadwiga, in: Jadwiga Czachowska; Alicja Szałagan, eds., Wspołcześni polscy pisarze i badacze literatury. Słownik biobibliograficzny, vol. 10: Ż, Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 2007, pp. 66–69.

Bio prepared by Gabriela Rogowska, University of Warsaw, g.rogowska@al.uw.edu.pl

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

This story is an adaptation of the Heracles’ myth covering selected stories from ancient sources. Among them, the story of the Twelve Labours and a few other stories were originally interpreted by Żylińska. For instance, the first reason for the Twelve Labours is not penance for the murder of wife and children but an attempt to reconquer the kingdom of Tiryns from which Eurystheus’ father banished Amphitrion and Alcmene. The second reason is the hero’s wish to marry Eurystheus’ daughter, Admete. During the performance of his Labours, Heracles is described as a hero, who, by killing monsters and fulfilling other heroic tasks, introduces new rules to the world established by Zeus (the hero is called “a son of Zeus who seized the highest power on Olympus, and on Earth dethroned the Mother decreeing the Father to be the head of the family,” p. 35). Heracles performed his labours, but Eurystheus refused to keep his promise to let him marry his daughter, arguing that the hero had gone mad in Tartarus. Heracles left Eurystheus, and finally, after some adventures (including servitude at Omphale’s court), married Deianira. However, he had to leave her father’s court after accidentally killing Deianira’s cousin. He then met Nessus, whose blood, combined with Deianira’s jealousy, became the main cause of his death.

Analysis

Żylińska gives her interpretation of the myth of Heracles using the most important and well-known plots connected with the Greek hero. It is, in principle, based on ancient sources, although with many omissions or changes. Some omissions concern less relevant stories (for example, we are not told that Heracles had a twin brother, slayed the Cithaeron lion, was romantically involved with 50 daughters of Thespius, freed Hesione of Troy, or married Hebe). In other cases, the author wanted to avoid cruelty in a children’s book (for example, there are no details of the eighth labour – the stealing of Diomedes’ mares or of the mutilation of the Erginus of Orchomenos’ heralds, whom he deprived of their ears and noses). However, some plots are omitted for other reasons, such as the marriage with Creon’s daughter, which was the declined reward for defeating Orchomenos’ warriors. By removing Megara’s story, Żylińska, first of all, avoids talking about Heracles’ madness, the killing of his family and the consequences of this crime. Nonetheless, it serves the narrative strategy similar to fairy tales in which a brave man earns the hand of a princess as a reward for his deeds. Thus Heracles is expected to win his princess’ heart and a part of the kingdom by completing the 12 Labours. Admete, Eurystheus’ daughter, is his chosen bride.

Another kind of adjustment is a slight “tweaking” of Heracles’ character. He is not only brave, strong and eliminates evildoers and monsters, but he is also described as a messenger of the Hellenic culture and an example of good conduct. Having defeated Geryon and his sons, he does not conquer barbarian peoples of Iberia to enslave them but instead liberates them and introduces civilized rules, like the guest’s holy right of hospitality. He also forbids them to murder strangers (p. 54). In addition to the tasks given by Eurystheus, he defends the oppressed; a knight saving damsels in distress. Like when he finds three young ladies tied up by pirates on an uninhabited island, he fights with their kidnappers. The freed ladies prove to be the Hesperides, and their father Atlas (here, an astronomer whom the myths have later turned into a titan holding the sky) gives Heracles the golden apples out of gratitude. Such change to the ancient sources allows the child reader to receive a moral lesson that kindness and chivalry pay off.

Unfortunately, Heracles not only slew monsters but also killed innocent people. The author could not overlook that. She described him as guilty but actually innocent. Thus, Linos, the first man Heracles killed, is said to be a random or collateral victim; the Centaurs met at Pholus’ are only injured in a fight (we learn later that they died from the poisoned arrows); king Diomedes’ death is not mentioned; Hippolyta is killed because of his extraordinary strength; Iphitus’ death was an accident, and the boy who dies during a feast in Calydon is also killed unintentionally. Heracles is considered innocent as he does not intend to kill them, and each case of manslaughter is of great concern to him. He admits full of remorse: „My own strength is a burden for me. I did not want to kill Linus. I did not want to kill the queen of the Amazons. When I strike, it is like a battering ram which crushes everything in its way” (p. 51). After Iphitus’ death, he atones for the killing as a slave to Queen Omphale, and his last manslaughter upsets him so much that he leaves home for a voluntary exile. Even the killing of King Augeas, committed years later (obviously not in the spur of the moment), is described as a military intervention against injustice. As Augeas tricks Heracles and pays for his labour with mockery instead of a tenth of his herds, Żylińska gives Heracles the moral right to revenge. The incident is even described as a simple consequence of a promise given to the treacherous Augeas (“I will be back and then we will set our accounts”, p. 39). Heracles leads the army against the perfidious king twice. Augeas dies shot by an arrow, not from Heracles’ hand.

In her interpretation, Żylińska also alludes to “feminist theology” or the “Goddess movement” popular in the 1970s, especially in the story of Hippolyta’s Girdle. Hippolyta is presented as an enemy because she believes in Mother Earth, while Heracles is the son of Zeus, who dethroned the Mother and established the Father as the head of the family (p. 49). Therefore, he is a foe of Mother Earth, and thus Hippolyta and Heracles are antagonists without even knowing each other. The author also mentions the cult of the Great Goddess.

The story ends with a summary of the most important episodes of Heracles’ myth – Heracles disappears in flames, but his myth endures in culture, language and school curricula across all of Europe as part of Greek civilization.

Further Reading

Marzec, Lucyna, Gatunki pisarstwa historycznego Jadwigi Żylińskiej (rozprawa doktorska pod kierunkiem prof. dr hab. Ewy Kraskowskiej), Poznań: UAM, 2012, http://sabatnik.pl/articles.php?article_id=259 (accessed 08.03.2012). (currently inaccessible)

Marzec, Lucyna, "Jadwiga Żylińska— kapłanka, amazonka, czarownica," Trzy kolory. Sabatnik boginiczno–femistyczny 6 (2011), http://sabatnik.pl/articles. php?article_id=259 (accessed 08.03.2013). (currently inaccessible)

Fiałkowski, Tomasz, "Łańcuch dziejów, łańcuch życia: Jadwiga Żylińska”, Tygodnik Powszechny. Katolickie pismo społeczno-kulturalne 21 (2009): app. XVII.

Kraskowska, Ewa, "Her Story w twórczości Jadwigi Żylińskiej”, FA-art. Kwartalnik Ruchu „Wolność i Pokój” 3 (2009): 26–33.

Marzec, Lucyna, Po kądzieli. Feministyczne pisarstwo Jadwigi Żylińskiej, Poznań: Wydawnictwo Nauka i Innowacje, 2014.

Sucharski, Robert A., “Jadwiga Żylińska’s Fabulous Antiquity”, in Katarzyna Marciniak, ed., Our Mythical Childhood... The Classics and Literature for Children and Young Adults, Boston–Leiden: Brill, 2016, 120–126.