Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

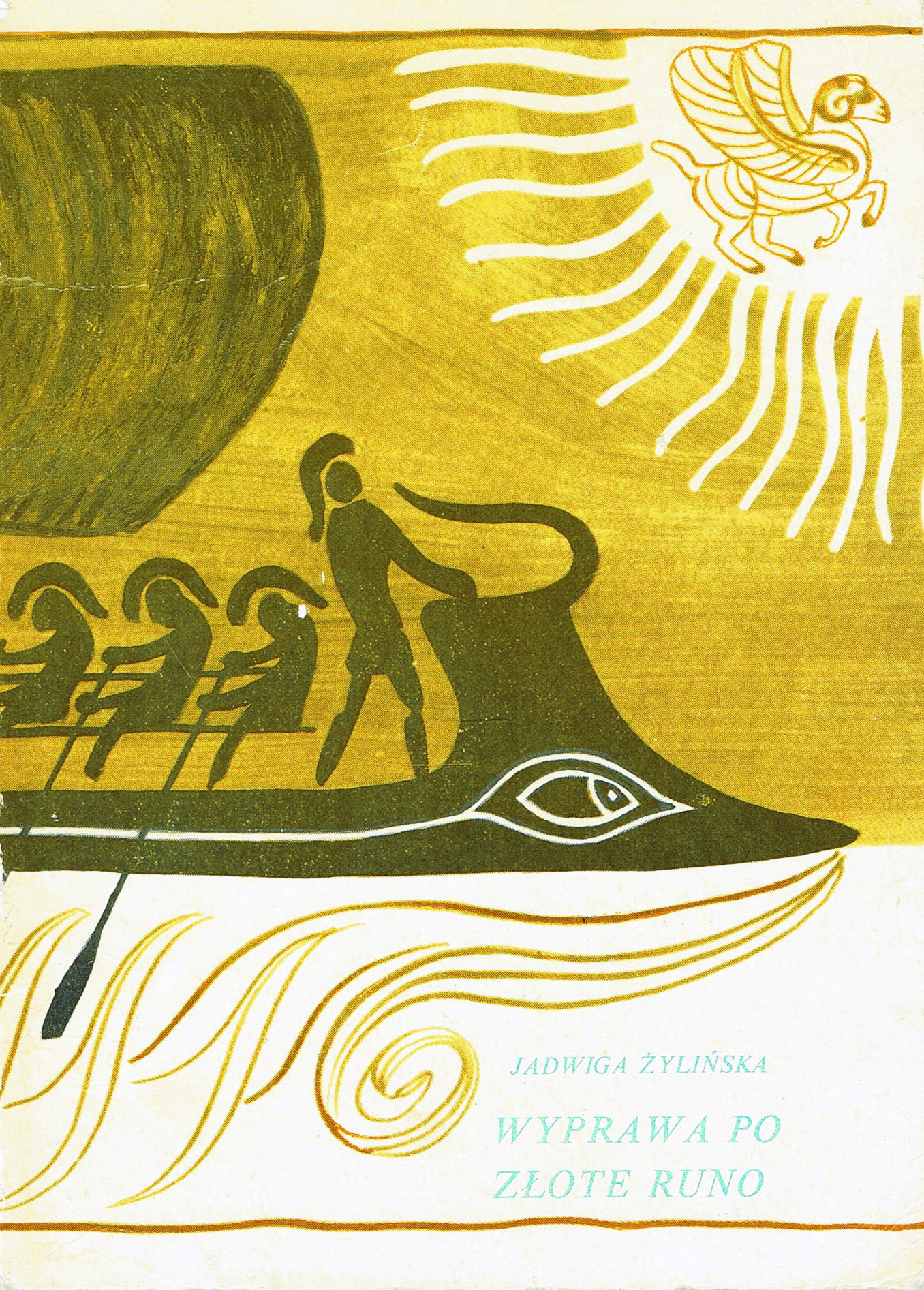

Jadwiga Żylińska, Wyprawa po złote runo. Warszawa: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza RSW „Prasa–Książka–Ruch”, 1974, 70 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Adaptations

Myths

Target Audience

Children

Cover

The publisher of the text closed down in 1990 leaving no known successors, and we were unable to determine if there are any copyright holders. Including the cover in our database meets all fair use requirements, still, we invite the users to share with us any information they may have about copyrights to the posted materials.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Ewa Wziętek, University of Warsaw, ewawzietek@student.uw.edu.pl

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

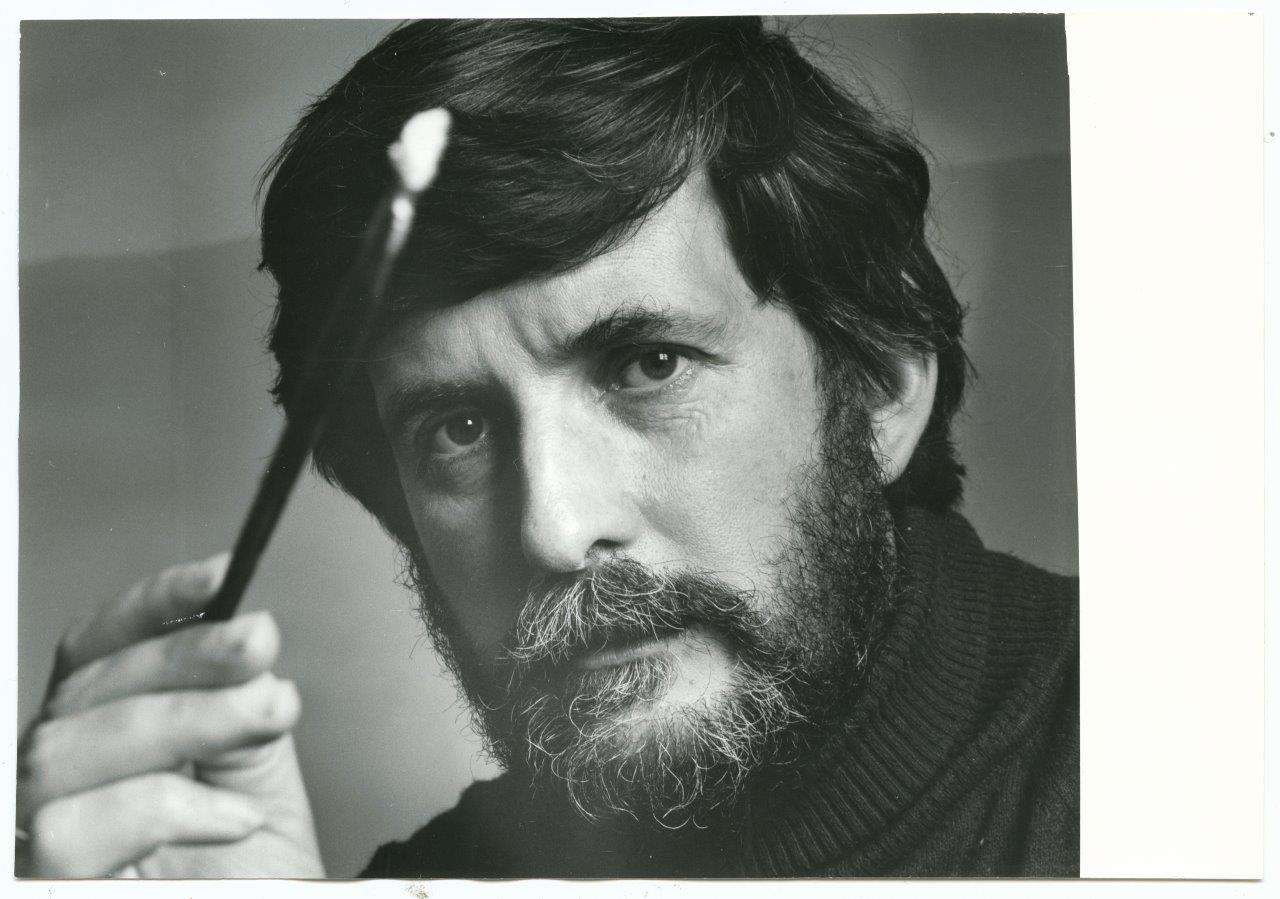

Courtesy of Barbara Towpik-Roszkiewicz, daughter of the artist.

Janusz Towpik

, 1934 - 1981

(Illustrator)

Janusz Towpik (1934–1981), originally from Cieszyn, was an architect with a diploma from the Warsaw University of Technology [Politechnika Warszawska] (1959). He also studied graphic design at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw [Akademia Sztuk Pięknych] and became a graphic designer and an illustrator. He designed postcards, stamps, matchbox labels, ex libris, logotypes, tapestries and intarsias.

Towpik illustrated children’s books, textbooks, fairy tales, and other stories to be viewed with a projector, nature atlases, popular science books, especially those about animals, and produced zoological tables for the PWN Encyclopaedia. In addition, he taught drawing at the Faculty of Architecture of the Warsaw University of Technology and conducted an arts club for children at the Warsaw Zoo.

Selected publications illustrated by Janusz Towpik, examples of his works, awards and exhibitions can be viewed online here and here (accessed: September 9, 2021).

Sources:

janusztowpik.pl (accessed: September 9, 2021),

"Janusz Towpik", at Artinfo.pl (accessed: September 9, 2021),

"Janusz Towpik. Natura i Fantazja", at ownetic.com (accessed: September 9, 2021),

"Janusz Towpik – Czarodziej Natury", at muzeum.edu.pl (accessed: September 9, 2021),

Gieżyński, Stanisław, Zwierzęta małe i duże, at Weranda.pl (accessed: September 9, 2021),

Towpik-Roszkiewicz, Barbara, Janusz Towpik, at Legendy Polskiego Jeździectwa website (accessed: September 9, 2021).

Bio prepared by Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

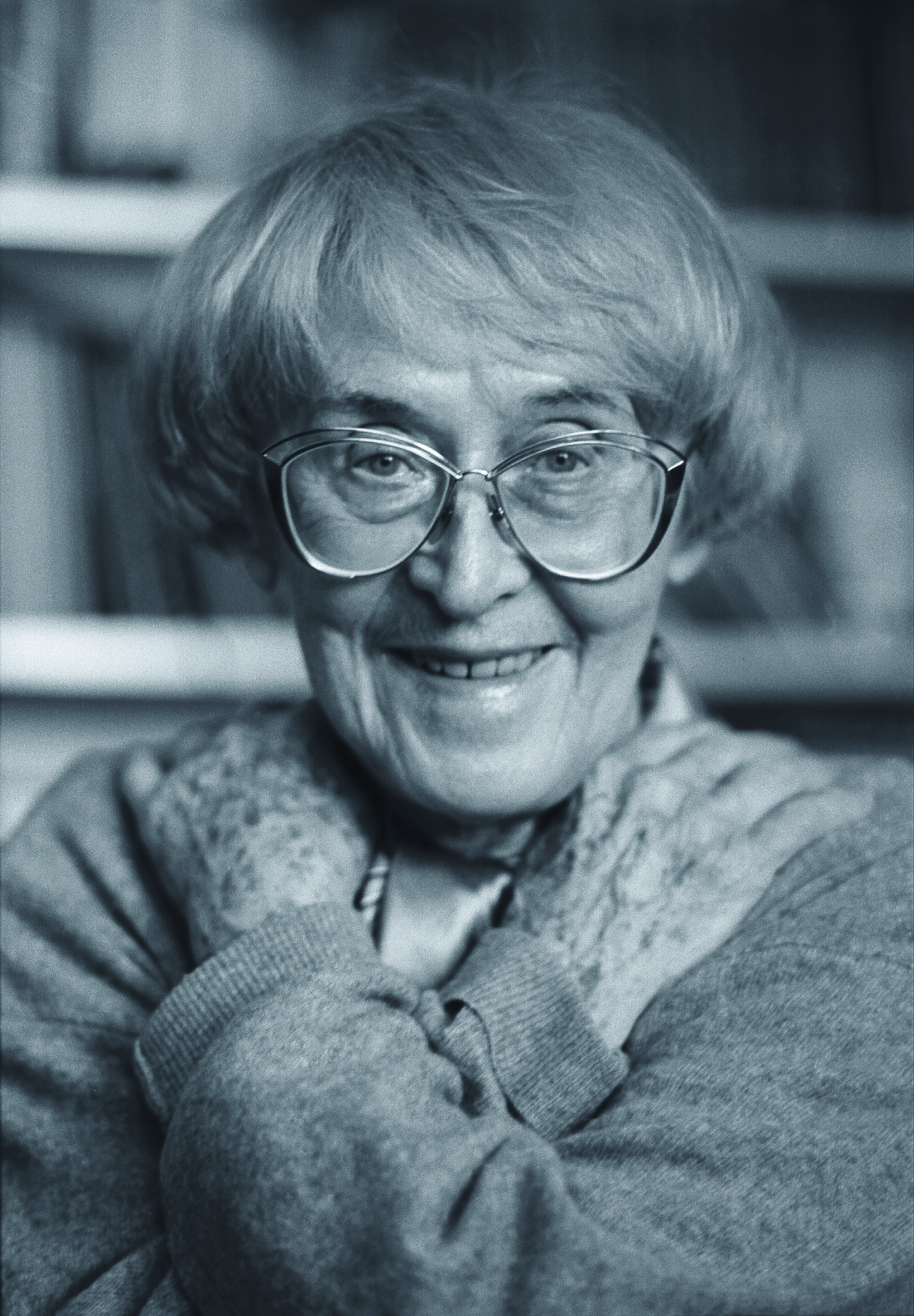

Photograph courtesy of its Author, Elżbieta Lempp.

Jadwiga Żylińska

, 1910 - 2009

(Author)

Born in Wrocław, lived in southern Wielkopolska [Greater Poland] (Ostrzeszów and Ostrów Wielkopolski), which influenced her later life. Graduated in English philology from the University of Poznań. Proficient in Latin, ancient Greek, English, and French. For many years worked for the Polish Radio. Prose writer, essayist, author of screenplays, radio dramas, historical novels, and books for children and young readers. Well known as an author of historical novels written from a woman’s point of view (the most important among these is a 2-volume novel Złota włócznia [The Golden Spear], 1961–1964). She made her debut in 1931 with a story for children Królewicz grajek [The Prince Piper] published in a periodical (still under her maiden name Michalska). Since 1964 member of the Polish PEN Club, in 1993 received the Polish PEN Club prize for lifetime achievement as a prose writer. Decorated with the Knight’s Cross of Polonia Restituta for outstanding achievements for Polish culture. Some of her books were translated into German and Russian. She is the author of a cycle Oto minojska baśń Krety [Here is the Minoan Tale of Crete], 1986, parts of which were also published separately.

Source:

Żylińska Jadwiga, in: Jadwiga Czachowska; Alicja Szałagan, eds., Wspołcześni polscy pisarze i badacze literatury. Słownik biobibliograficzny, vol. 10: Ż, Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 2007, pp. 66–69.

Bio prepared by Gabriela Rogowska, University of Warsaw, g.rogowska@al.uw.edu.pl

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

The story begins when Iolcos, an ancient Thessalian city, was ruled by the usurper King Pelias. Pelias deprived his brother Aeson of the throne, but he didn’t know that Aeson’s lawful successor – Jason – was alive. Jason lived with the Centaurs and was brought up by one of them – the wise Chiron. Unexpectedly, Jason came to Iolcos to take back his throne. Pelias agreed on the condition that Jason would bring back the famous Golden Fleece. So Jason and his 49 companions (the Argonauts) built a ship (the Argo) and departed for the long and dangerous journey to Colchis.

After many days and many adventures, they finally reached Colchis. The king of Colchis – Aeëtes – entertained the Argonauts in his palace as if they were safe there. But they weren’t. Aeëtes did not want to give the Golden Fleece to the Argonauts. Pretending kindness, Aeëtes offered Jason his daughter – the sorceress Medea, but only on the condition that he would accomplish a nearly impossible task of harnessing two fire-breathing bulls, plough the field with the help of the bulls and vanquish the Sown Men. Jason agreed because due to Aphrodite’s intervention, he fell in love with Medea. The sorceress loved him too and decided to help him. She stole the Golden Fleece and ran away with Jason and the Argonauts. Medea was so desperate and in love that she did not prevent the death of her brother Apsyrtus, who had set off in pursuit of the Argo and was killed by Jason (a less popular version of the myth, according to which Apsyrtus was sent to pursue Medea). Jason and Medea married and came back to Iolcos. Jason’s parents were murdered by Pelias. Jason and Medea sailed to Corinth and settled there. Afterwards, Jason left Medea for another woman. The sorceress took an act of cruel revenge. She set the palace on fire, killing Jason’s new lover.

Analysis

Żylińska’s adaptation is aimed at children, which is obvious from the very beginning. Before retelling the myth as such, she introduces the story’s background in a few words, saying where the ancient Colchis was, how the early Greek cities functioned and how the heroic tales increased their prestige. As Jason’s tales were embedded into poetry, they widely spread and have lasted till today, introducing the Golden Fleece into European vocabulary. The narration is full of descriptions and dialogues and resembles a folk tale to make the reading easier for children. However, this simplicity suffers sometimes, as archaic vocabulary and grammar are difficult for today’s children who know the contemporary language. However, from the perspective of children’s books of that period, such archaization is not unusual.

In the beginning, the story concentrates on the character of Jason against the rich tapestry of the other characters and stories. It is done either to explain the plot better or to highlight the importance of the hero. Thus the subplots of Pelias’ rule or Phrixus’ flight provide some explanations, and the characters of Chiron or the Argonauts add value to the image of the young protagonist. The course of the journey is described according to Apollodoros (Lemnos, Doliones’ land, land of the Bebryces, dwelling of Phineus, Symplegades, Stymphalian Birds’ island and saving of the shipwrecked sons of Phrixus and Chalciope). Still, certain secondary plots and selected details not appropriate for children are omitted (for example, the story of Hylas is omitted, and the Lemnian women banish their husbands instead of killing them, though “there was a persistent rumour that they had killed them in revenge for favouring Thracian women, captured in war”, p. 18).

From the moment the crew reaches the Colchian shore, a new protagonist takes over the leading role. Medea is the true heroine there, a character full of compassion and emotions, loving, helpful, brave, without even a shadow of ill will in her heart. The most challenging quest during the entire journey – the extremely dangerous and unattainable tasks set by the sneaky Aeëtes – thanks to Chalciope and Medea are not even attempted, which detracts from Jason’s achievements. Out of fear of king Aeëtes, who could doom the strangers and her sons for leading them in Colchis, Chalciope asks Medea to do anything to save the Greeks and Phrixus’ sons as well; this is in accordance with Apollonius’ version. Medea undertakes the challenge of saving the Argonauts before the deathly trials could begin – she helps to steal the fleece out of love for her sister. Such emphasis on the role of women and particularly of Medea can be linked to “feminist theology”, a movement popular in the 70s. In Żylińska’s adaptation, Medea is also not responsible for the tragic fate of her half-brother Apsyrtus. Apsyrtus – here an adult man – is sent by their father to capture Medea, and they both head to their aunt, Circe, for her valuable advice. Medea meets her brother on a holy island to negotiate face to face, and it is Jason who unexpectedly ambushes and stabs the unaware Apsyrtus, while Medea covers her face with a vail, not wanting to see her brother’s death. In this interpretation, Medea is not a cold-blooded murderer who chops a small boy without blinking an eye – she first tries to convince Apsyrtos to cease the pursuit and, after his death, seeks Circe’s help to purify the family.

Another adjustment made for the child reader is the fate of the protagonists after their return to Iolcus. Jason is told that his parents were murdered and wants to avenge them. Among his crew, there is Pelias’ son and his daughter’s fiancé, so the Colchian treasure is divided, the Argonauts are spared, and Jason sails with Phrixus’ sons to their Beotian grandfather and then to Corinth. The Golden Fleece is sacrificed to Zeus in Orchomenos. Thus the part of the myth in which Medea cruelly disposes of Pelias is also omitted. Nevertheless, the character of Medea is not entirely flawless – in the story told by an older man (who is Jason himself sitting in the shadow of Argo), she is described as the one who set fire to a Corinthian palace out of unhappiness and revenge on her unfaithful husband who abandoned her. As everyone in the palace perished in the fire, Medea was responsible for their deaths, but again – the filicide is not mentioned, not even as a possible rumour.

Further Reading

"Argonauci", "Jazon", in Stanisław Stabryła, Słownik szkolny. Mitologia grecka i rzymska, Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 1997, 33, 115.

Apollodorus, The Library with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer in Two Volumes, London: William Heinemann, New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1921 (accessed: September 2, 2021).

Apollonius Rhodius, The Argonautica, (eBook based on: Seaton, R.C., ed., trans., Apollonius Rhodius: Argonautica, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA, 1912). (accessed: September 2, 2021).

Lovatt, Helen, In Search of the Argonauts. The Remarkable History of Jason and the Golden Fleece, London: Bloomsbury, 2021.

Sucharski, Robert A., “Jadwiga Żylińska’s Fabulous Antiquity”, in Katarzyna Marciniak, ed., Our Mythical Childhood... The Classics and Literature for Children and Young Adults, Boston–Leiden: Brill, 2016, 120–126 (accessed: November 2, 2021).