Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Енеида. На малороссійскій языкъ перелиціованная И.Котляревскимъ [Eneyda. Na malorossiĭskiĭ iazyk perelytsiovannaia Y. Kotliarevskym]. Saint Petersburg: Izhdiveniem M.Parpury, 1798.

The first edition contained only 3 parts of the poem.

In 1809 I. Kotliarevsky produced his own edition of the first four parts: Виргиліева Енеида. На малороссійскій языкъ перелиціованная И. Котляревскимъ / Virgil’s Aeneid. Travestied Inside Out into Little Russian language by I.Kotliarevsky, Kharkiv, 1809.

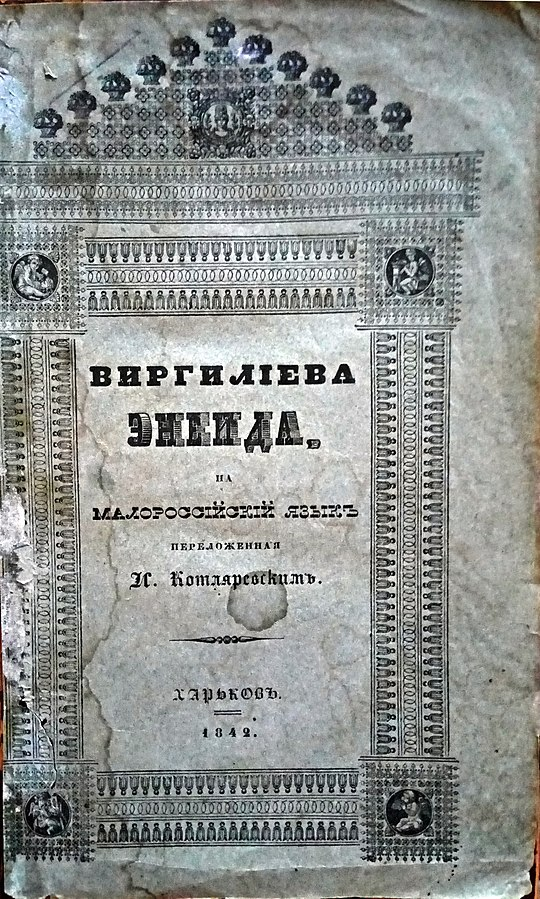

The full edition of the poem was first published only after the death of I. Kotliarevsky in 1842 in Kharkiv.

Available Onllne

wdl.org (accessed: May 15, 2018)

Genre

Mock-heroic poetry

Target Audience

Young adults (see addenda)

Cover

Retrieved from Wikipedia Commons (edition from 1842, Char'kow), licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International (accessed: December 12, 2021).

Author of the Entry:

Maria Pushkina, National Academic Janka Kupała Theatre, maryiapushkina@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Retrieved from Wikipedia (public domain).

Ivan Kotliarevsky

, 1769 - 1838

(Author)

Ivan Kotliarevsky is known as “the first modern Ukrainian writer”. He was born in Poltava into the family of a government clerk. Kotliarevsky studied at Poltava Theological Seminary (1780–1789), he worked as a private tutor (quite a popular profession those days) after graduation. He worked in small villages across the country, and this way he gained a deeper understanding of Ukrainian folklore and everyday rural routines. In 1796–1808 he served in the Imperial Russian Army and took part in the Russo-Turkish War. After his retirement from the Army, he served as a supervisor at school for children of impoverished noble families. During Napoleon’s invasion of Russia (1812) he organized a Cossack regiment in the town of Horoshyn, and attained the rank of major. In 1816–1821 Kotliarevsky was managing Poltava Theatre. His two plays (Natalka Poltavka/Natalka from Poltava and Moskal-Charivnyk/The Muscovite-Sorcerer) are living classics of Ukrainian literature. His best-known literary work is the Cossack Aeneid, which is considered to be the very first poem (as well as the first ever literary work) to be published in the “modern” Ukrainian language.

Bio prepared by Maria Pushkina, National Academic Janka Kupała Theatre, maryiapushkina@gmail.com

Translation

Belarusian: Энеіда, trans. A. Kuliashoŭ, Minsk: Belarus, 1969.

Bulgarian: Енеида, trans. K. Kadiĭski, Sofia: Narodna kultura, 1987.

Czech: Aeneida, trans. M. Marčanová, Z. Hanusova a J. Tureček-Jizerský) SNKLHU, Praha 1955.

English: Eneida, trans.C. H. Andrusyshen, W. Kirkconnell / The Ukrainian Poets 1189–1962, selected and trans. into English verse by C. H. Andrusyshen and W. Kirkconnell, Toronto, 1963; Aeneid, trans. B. Melnyk, Toronto: The Basilian Press, 2004.

German: Aeneida, trans. I. Katschaniuk-Spiech; ed. Leonid Rudnytzky, Ulrich Schweier, München: Ukrainische Freie Universität, 2003; Aeneide. Teil I, trans. O. Hrycaj, Wien, Ukrainische Nachrichten 37 (1915).

Georgian: ივან კოტლიარევსკი ენეადა; უკრ. თარგმნა ამირან ასანიძემ; რედ. ავთანდილ გურგენიძე, და სხვ.; წინათქმა რევაზ ხვედელიძე; მხატვ. ანატოლი ბაზილევიჩი, თბ., 2011. 324გვ.

Polish: Eneida, trans. P. Kupryś, Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL, 2008; Eneida, trans. P. Kupryś, Lublin: Polska Akademia Nauk; Kiev: Narodowy Uniwersytet Biologicznych Źródeł Energii i Wykorzystania Przyrody, 2013; Eneida. Część pierwsza, trans. J. Pleśniarowicz, F. Nieuważny / Antologia poezji ukrainskiej, Warszawa: Ludowa Spoldzielnia Wydawnicza, 1976.

Russian: Энеида, trans. I. Brazhnin, Moscow: Gospolitizdat, 1953; Энеида, trans. K. Khudenskiĭ, Kaliningrad: Izdatelstvo gazety Kaliningradskaia Pravda, 1957; Энеида, trans.V. Potapova, Moscow: Gospolitizdat, 1961; Энеида, trans. and modernization A. Kondratenko, Rostov na Donu: Rost.kn.izd-vo, 1998; Энеида, trans. N. Il’in, Kirovograd: Ekskluziv-Sistem, 2013.

Romanian: Eneida, trans. A. Covaci, I. Covaci, Bucureşti: Editura Mustang, 2001.

Summary

After the fall of Troy, Aeneas ("Aeneas was a lively fellow, / Lusty as any Cossack blade") and the Trojans run away to sea. Juno asks Aeolus to sink the Trojans. Aeolus creates the storm, but Aeneas gives Neptune a bribe, and the storm calms down. Venus feels worried about her son Aeneas and complains about Juno to Zeus. Zeus says that the fate of Aeneas is already sealed – he will go to Rome and found a strong state there. After much suffering, the Trojans reach Carthage, where Dido is the Queen. Dido falls in love with Aeneas, who reciprocate her love and forgets about his main goal, to reach the site of the future city of Rome. Zeus sends Mercury to remind Aeneas of his mission, Aeneas leaves Carthage, and Dido burns herself at the stake. The Trojans land in Sicily where they are hospitably received by King Acestes. Aeneas wants to commemorate his father – Anchises. Juno persuades women to set fire to the Trojan ships, but the other gods extinguish the flames. Anchises appears in Aeneas’s dream and asks his son to visit him in the realm of the dead. Aeneas, accompanied by the Sibyl, seeks a road to the Underworld near the town of Cumae. They descend into the realm of the dead and cross the Styx. Aeneas meets with Dido and his fellow Trojans. Anchises prophesies his great future feats. The Trojans sail further, and Aeolus helps them to circle the island of Circe. On the island of King Latinus, Aeneas quickly learns Latin and fights for the hand of king’s daughter Lavinia. The Trojans want to collude with the Rutulians, the enemies of Turnus, Aeneas’s competitor. There are disturbances in the camp of Aeneas. Turnus, deprived of divine help, dies in a fight with Aeneas.

Analysis

The poem was created under the influence of the Russian Aeneid by Nikolaĭ Osipov (supplemented by Aleksandr Kotelnitskiĭ), which was inspired by a similar work by Aloys Blumauer. Kotliarevsky’s Aeneid consists of six parts, which correspond to the similar sections of the Russian travesty version of Virgil’s Aeneid. The plot accurately repeats the parts of Virgil's Aeneid that were chosen by Nikolaĭ Osipov for his edition. However, Kotliarevsky transfers the action to other historical realities, transforming Aeneas into a Cossack who returns home after the liquidation of the Zaporozhian Sich. The plot is brightly complemented by the descriptions of provincial routine of local noblemen, their meals, feasts, customs, traditions and lifestyle. The Cossack line forms the structure of the plot. This is why the poem is known to be an encyclopedia of Ukrainian culture and its characters bear the national features of Ukrainian people. Anchises prophesies the creation of "a new powerful state," which makes the Ukrainian Cossack Aeneid sound like a hopeful testament to restore the country's former political greatness.

In addition to a total reinterpretation of the poem, Kotliarevsky includes folk songs and images of folk mythology to the text, which is typical for travesty and burlesque literature. Following Osipov, the author changes the description of hell (striving rather for a folk concept), because "since the time of Virgil, the kingdom of the dead has changed significantly." The use of folklore traditions, oral poetic tradition and humor (along with macaronic language) has made a strong contribution to the emergence of a new kind of readership that consisted of simple peasants. Educated young people were also attracted by the text since Virgil remained an important cultural code for them.

The diverse and rich language of the poem became a landmark in the formation of the Ukrainian literary standard, and the text itself became the basis for many works of art from animated films and post stamps to operas, rock operas and large museum projects.

Further Reading

Paulouskaia, Hanna, Virgil Travestied into Ukrainian and Belarusian: The Afterlife of Virgil, London: University of London, Institute of Classical Studies, 2018, 101–122.

Shablovsky, Ėvgen; Derkach, Boris [Шабліовський, Євген; Деркач, Борис], "І.П. Котляревський – корифей української літератури" [I.P. Kotliarevsky – a coryphaeum of Ukrainian literature (I.P. Kotliarevs'kyĭ – korifieĭ ukraïns'koï literatury)], in: I.P. Kotliarevsky, Повне зібрання творів [A complete collection of works (Povne zibrannia tvoriv)], Kiev: Naukova dumka, 1969.

Steshenko, Ivan [Cтешенко, Иван], "И. П. Котляревский и Осипов и их взаимоотношения" [I.P. Kotliarevsky and Osipov and their relationship (I.P. Kotliarevskiĭ i Osipov i ich vzaimootnosheniia)], Kievskaia starina 7–8 (1898), 74–78.

Studinsky, Kyrylo [Студинський, Кирило], Козацтво й гайдамаччина в "Енеїді" Котляревського, [Cossacks and Haidamachians in Kotliarevsky’s Aeneid (Kozactvo ĭ gaĭdamachchyna v Eneїdi Kotliarevs'kogo)], Lvov: Literaturni zamitky, 1901.

Zalashko, Anatoliĭ [Залашко, Анатолій], ed., Іван Котляревський у документах, спогадах, дослідженнях [Ivan Kotliarevsky in documents, memoirs, studies (Ivan Kotliarevs'kyĭ u dokumentah, spogadah, doslidzenniah)], Kiev: Dnipro, 1969.

Addenda

Енеида. На малороссійскій языкъ перелиціованная И.Котляревскимъ / Aeneid. Travestied Inside Out into Little Russian language by I. Kotliarevsky; that was the title of the first edition published without the knowledge of the author. The later editions usually have the title: Енеїда / Aeneid.

Target group: young educated adults, but “the low folk language” made it popular among a wide range of readers; nowadays the poem is included in the required reading list for 9th grade (14–15 years old).