Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

Available Onllne

ru.wikisource.org (accessed June 30, 2018).

Genre

Mock-heroic poetry

Target Audience

Young adults

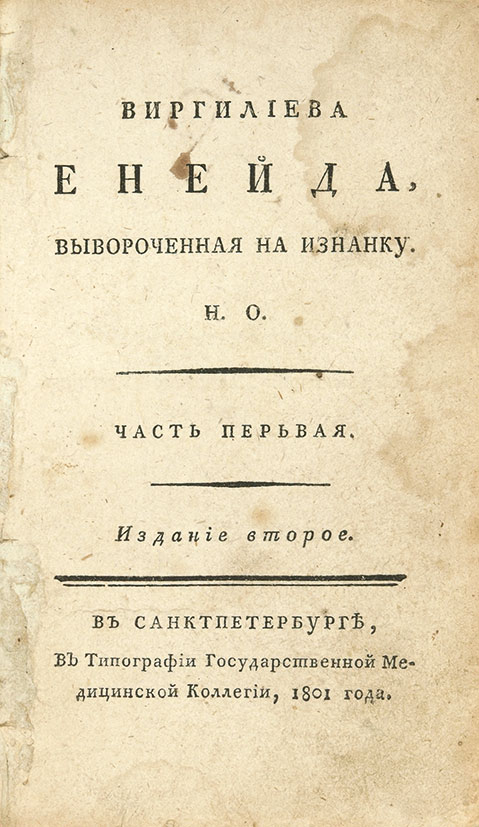

Cover

Nikolai Osipov, Aeneid, 1801 (3rd edition). Retrieved from Wikipedia Commons, public domain (accessed: December 30, 2021).

Author of the Entry:

Maria Pushkina, National Academic Janka Kupała Theatre, maryiapushkina@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Daniel A. Nkemleke, University of Yaounde 1, nkemlekedan@yahoo.com

Nikolaĭ Osipov

, 1751 - 1799

(Author)

Nikolaĭ Osipov (Николай Осипов) was a Russian writer, poet and translator. He was born in Saint Petersburg. As he stated himself, his parents were civil servants. Osipov received his primary education at home, then he studied languages (French and German), architecture and mathematics in a private school. In 1769 he became a soldier of the famous Izmaĭlovskiĭ Regiment. During their military service, Osipov and his colleagues edited a periodical handwritten magazine, where some of his poems, prose and translations from French and German appeared. In 1781 Osipov retired. He continued writing and translating, he also edited his own magazine. After 1790 he worked as a translator for The Secret Office. Nikolaĭ Osipov left a large literary heritage, but the Virgil’s Aeneid Travestied Inside Out is the best known of his works.

Bio prepared by Maria Pushkina, National Academic Janka Kupała Theatre, maryiapushkina@gmail.com

Summary

Virgil’s Aeneid Travestied Inside Out by N. Osipov is remarkably close to Vergil’s Aeneid in plot. Every part (song) of the poem is preceded by a short summary of what the part narrates. After the fall of Troy, a fleet led by Aeneas (“a daring young man, / And the most skillful fellow”) begins a long voyage to find a new home. Juno wants to disturb them, she asks Aeolus to set a storm, which will destroy the Trojan fleet. Neptune, angry with Juno's intervention into his domain, calms the sea. Aeneas and his people take shelter on the coast of North Africa. There Aeneas meets his mother, Venus, that presents herself as a Gypsy woman. She inspires him to go to Dido, the queen of Carthage. Venus also tells Cupid to replace Ascanius, Aeneas little son. This way Cupid could awake Dido’s love feelings to brave and handsome Aeneas. Aeneas recounts the episodes of Trojan war and the fall of the city. The second part of his narrative depicts their voyage towards the unknown homeland. They have seen many miracles on their way. As Aeneas finishes his story, Dido realizes that she has fallen in love with her guest. Aeneas is in love too, but Jupiter sends Mercury to remind Aeneas of his duty, so he wants to depart from the city of Carthage and leave Dido, whose heart is broken. Dido commits suicide. The Trojan fleet reaches Sicily, where Aeneas receives a vision. His father tells him to go to the underworld. Aeneas, guided by Cumaean Sibyl, descends there, passes by Charon and Cerberus and speaks to the shadow of his father. When he comes back from the underworld, the Trojans head to Latium, where Aeneas courts Lavinia, the daughter of King Latinus. Aeneas wants to avoid war, but Lavinia is asked to be married to Turnus, the ruler of the Rutuli people, that’s why Aeneas decides to ask Rutuli’s enemies for help.

Analysis

This mock-epic poem was influenced by a German poem Abenteuer des frommen Helden Æneas by Aloys Blumauer (1784–1788; published in 1872) and by Paul Scarron’s Virgile travesty (1648–1653). Nikolaĭ Osipov wrote only four parts, the narration ends before the war in Latium begins. The fifth and the sixth parts of the Russian Aeneid were written by Aleksandr Kotelnitskiĭ later and published in 1802–1808. Nikolaĭ Osipov changed the rhythm of the narrative by creating the illusion of a folk tale and highlighting comical situations. More generally, Russian Aeneid owes its genesis to the fact that this period emphasized the translation of Greek and Latin literature into Russian (reading of the original texts was obligatory for school students). The Aeneid was translated in the 1770s by Vasilij Petrov (a personal translator of Catherine the Great), who used a very artificial, old-fashioned language. In this context, the burlesque poems could be interpreted as a free adaptation of Virgil in colloquial language. The usage of low folk language for the translation of the poem intensified the satiric effect.

Osipov's main goal was to create a dialogue with Virgil, so he dares to call Virgil by name and to make him responsible for his own verses. As in poetry competition (or lessons at school, which were also obligatory at that time), Osipov tries to write ‘a better version’ of the Aeneid, emulating the Roman poet. The work by Nikolaĭ Osipov (not the later parts written by Aleksandr Kotelnitskiĭ) became the inspiration and the basis for the Ukrainian and Belarusian texts.

Further Reading

Gavrilov, Aleksandr, Russia, in Manfred Landfester in cooperation with Hubert Cancik and Helmuth Schneider, eds., Brill’s New Pauly Encyclopaedia of the Ancient World, Classical Tradition 5, Leiden–Boston, 2006–2010, 1–18.

Karamzin, Nikolaĭ [Карамзин, Николай], Виргилиева Энеида, вывороченная наизнанку [Virgil’s Aeneid Travestied Inside Out (Virgilieva Ėneida, vyvorochennaia naiznanku)], Moscow: Московский журнал [Moskovskiĭ zhurnal], May 1792.

Martirosova Torlone, Zara, “Nikolai Osipov’s Aeneid turned upside down,”Vergil in Russia. National Identity and Classical Reception, Oxford, 2014: 90–107.

Paulouskaia, Hanna, “Virgil Travestied into Ukrainian and Belarusian,” The Afterlife of Virgil, London: University of London, Institute of Classical Studies, 2018, 101–122.

Titunik, Irwin R, A Note about Paul Scarron’s Virgile travesti and N. P. Osipov’s Eneida, Study group on Eighteenth-Century Russia, Newsletter 21 (September 1993): 51–56.

Vorob’iov, Yuriĭ [Воробьев, Юрий], Латинский язык в русской культуре XVII–XVIII веков [Latin in Russian culture of 17th–18th centuries (Latinskiĭ iazyk v russkoĭ kulture XVII–XVIII vekov)], Saransk: Izd-vo Mordovskogo Universiteta, 1999.

Addenda

The first and second parts of Osipov's The Aeneid were published in 1791, the third part in 1794, the fourth in 1796 in St. Petersburg at the expense of I. Shnor. In 1800 (after Osipov's death), all four parts were republished and printed together by the Imperial Printing House at the expense of I. Glazunov. The third edition (St. Petersburg, 1801) was marked as “The Second Edition”.