Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Yung In Chae, Goddess Power: A Kids' Book of Greek and Roman Mythology: 10 Empowering Tales of Legendary Women. Emeryville, CA: Rockridge Press, 2020, 124 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Adaptations

Retelling of myths*

Target Audience

Children (9–12 year olds)

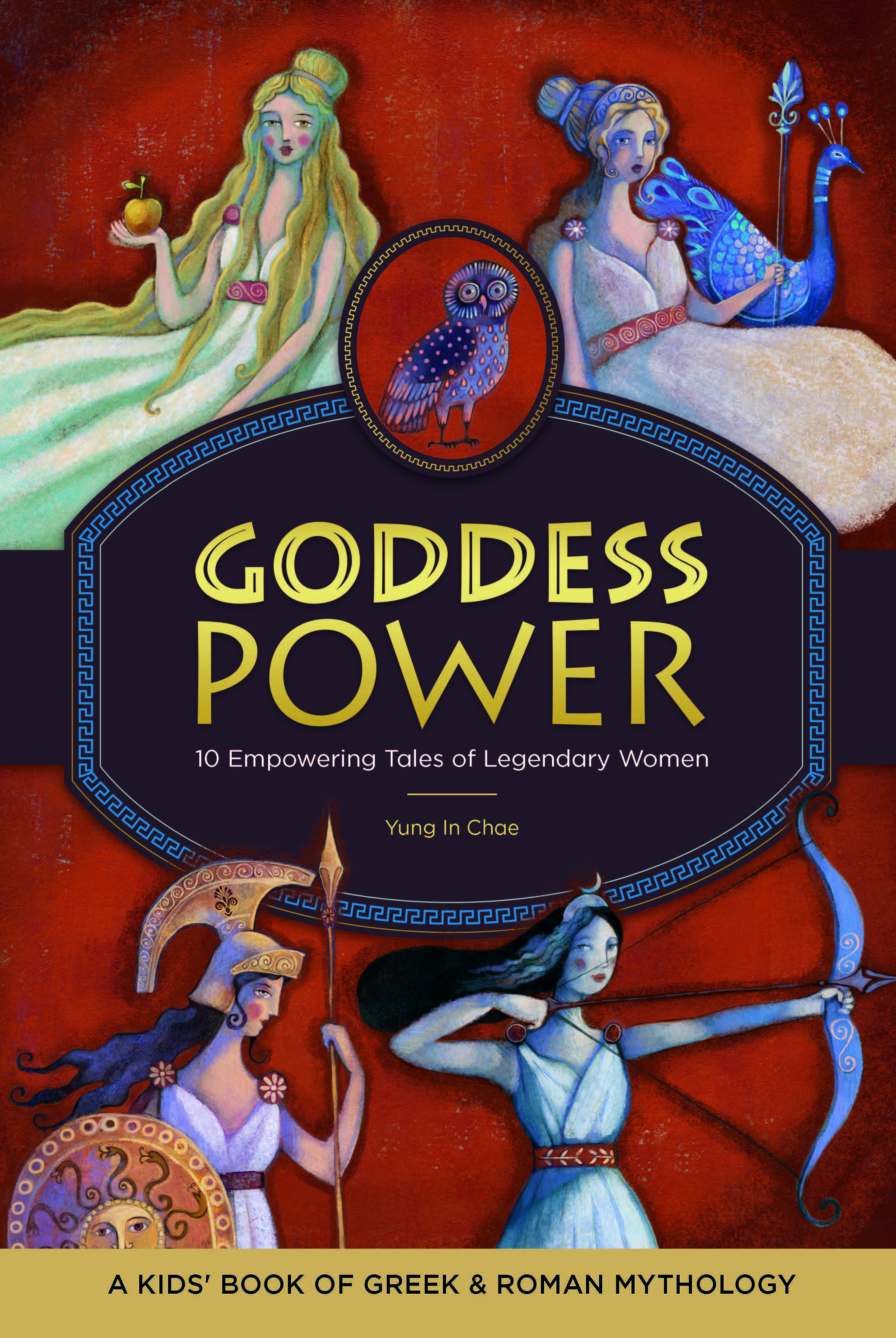

Cover

Cover courtesy of Rockridge Press.

Author of the Entry:

Ayelet Peer, Bar-Ilan University, ayelet.peer@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Photo courtesy of the Author.

Yung In Chae (Author)

Yung In Chae is a writer, editor and journalist from Seoul, South Korea. She graduated from Princeton University with a B.A. in Classics and holds an M.A. in History and Civilizations from the École des hautes études en sciences sociales in Paris. She has an MPhil in Classics from the University of Cambridge where she was a Gates Cambridge Scholar. Yung In Chae is also an editor-at-large of Eidolon.

Source:

Official website (accessed: August 10, 2020).

Bio prepared by Ayelet Peer, Bar-Ilan University, ayelet.peer@gmail.com

Questionnaire

1. What drew you to writing/working with Classical Antiquity and what challenges did you face in selecting, representing, or adapting particular myths or stories?

My publisher came to me with the idea for a children’s book about goddesses in classical mythology, not the other way around, but I agreed to the project because I believed in it. I’m happy to write for children; children actually read books. But even now there’s still a lot of sexism in children’s books and classical mythology is no exception. So that was a big challenge: figuring out how to avoid gratuitous sexism while not changing anything fundamental about the myths. I wanted the book to be feminist without coming across as pandering.

2. Why do you think classical / ancient myths, history, and literature continue to resonate with young audiences?

I’m unsure about the extent that they do in a global context so I don’t want to make overly broad statements. I will say though that while I was writing the book I was constantly reminded that myths are just a lot of fun. They have distinct characters, clear and exciting plots, sometimes profound morals. These are characteristics of good children’s books in general, not just ones about classical mythology.

3. Do you have a background in classical education (Latin or Greek at school or classes at the University?) What sources are you using? Scholarly work? Wikipedia? Are there any books that made an impact on you in this respect?

I have an A.B. in Classics (2015) from Princeton University and an MPhil in Classics from the University of Cambridge (2016). I drew upon a range of Latin and Greek sources but mostly from Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Hesiod’s Theogony, so those two texts had the greatest impact on this particular project.

4. Did you think about how Classical Antiquity would translate for young readers, esp. in (insert relevant country)?

My publisher wanted the book to be for children between the ages of 8-12, which is tricky because that’s a wide range and different children can demonstrate vastly different reading capabilities around that time. But it did mean that I had to downplay the more potentially traumatic aspects of the stories and at the same time not excise everything that’s difficult about them. Specifically, I was not allowed to depict sexual violence—and there’s a lot of that in classical mythology.

5. How concerned were you with "accuracy" or "fidelity" to the original? (another way of saying that might be — that I think writers are often more "faithful" to originals in adapting its spirit rather than being tied down at the level of detail — is this something you thought about?)

I decided early on that I wanted to stay pretty faithful to the original myths, although it’s unclear what “original” means here because stories often have multiple competing versions. I guess I wanted the myths to follow some basic, agreed-upon structure. So at times I added details that were my own but I never, for example, changed the ending of a myth. I wanted children to be able to read the book and come away with what could be reasonably called an accurate understanding of classical mythology.

6. Are you planning any further forays into classical material?

I will continue writing for Eidolon, the online Classics magazine where I’ve been working since 2015. There may be more books in my future but no concrete plans yet.

Prepared by Ayelet Peer, Bar-Ilan University, ayelet.peer@gmail.com

Photo courtesy of the Illustrator.

Alida Massari (Illustrator)

Alida Massari is an Italian artist. She specializes in children’s illustrations and has illustrated various books in different languages. Alida Massari specialized in illustration at the European Institute of Design. She finds inspiration for her work from ancient architecture and art as well as folk tradition. She also exhibited her work in Italy and abroad. Alida Massari won numerous awards for her art, among them: Language Learner Literature Award for the book Dorothy (2008), Sulle ali delle farfalle: Giochi d’acqua (2003), "Bollicine d’artista" ondazione Mostra Internazionale d’illustrazione di Sàrmede (Tv) e la Mostra nazionale di spumanti di Valdobbiadene (Tv) (2002).

Source:

Official website (accessed: August 10, 2020).t

Bio prepared by Ayelet Peer, Bar-Ilan University, ayelet.peer@gmail.com

Summary

The book focuses on Titaness, Goddesses and their adapted related myths. Before the actual myth, we have a short “identity card” for the goddess, including the pronunciation of her name, family,, symbols, strength and a few sentences of introduction on the goddess’ origin or role. The stories are as follows: Gaia and the creation of the world and the Titans, Rhea and Cronus and the birth of the gods, Hera and the myths of Io, Echo, Narcissus, Heracles. Artemis: her birth, Actaeon, Niobe. Athena: her birth, Athens, Arachne. Demeter: Persephone. Aphrodite: her birth, her affair with Ares, Adonis, the judgment of Paris. The Moirai: Asclepius, Alcestis, Meleager. The Muses: the Pierides. Circe: Scylla, Picus, Odysseus, Circe’s sons by Odysseus. The book also contains a list of mythological creatures with short explanations (for example Cerberus, Cyclops, Harpies etc.). The book also includes a pronunciation guide and a short glossary for the mentioned characters and places. Finally, the author mentions a list of resources, including ancient texts, children’s books and more advanced titles, such as Edith Hamilton’s Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes (1942), and Stephen Fry’s Mythos (2017). The stories are accompanied by lavish illustrations in pastel colours, predominantly shades of blue.

Analysis

The author is a specialist and this is visible from the myths she has chosen to retell. Even in the case of well-known stories such as Circe and Odysseus, she chose to include less familiar elements, for example Circe’s sons by Odysseus as well as Odysseus’ end.

In her introduction, the author explains her thematic choice for the book: “while there are plenty of books about classical mythology in general, goddesses rarely get to monopolize the reader’s attention. I wanted a space just for pondering female deities and, by extension, women and girls: all that we are, everything that we can do.” The book is meant to empower the young readers (probably appealing more to female but male readers will find it as engaging). However, the author cautions that the ancient deities should not be seen as role models; they have their share of good and bad qualities and they are flawed. They can be cruelly unjust and unkind. However, the author correlates between the imperfect goddesses and mortal women and girls, and elucidates: “they (the goddesses) simply exist, in all of their complexity – often, even that takes a lot of courage. What you take away from their accomplishments and mistakes is up to you. The stories offer possibilities, not instructions. And the possibilities are as varied as the goddesses themselves.” Hence the aim of the book is first for the readers to be familiar with the ancient tales and then, and even more importantly, to understand the power and might of the female characters who, while living in a patriarchal society (albeit a divine one), created their own fate. They may inspire the readers to act in ways opposite to the goddesses (hopefully be kinder and more compassionate), yet the fact that the goddesses posses such great powers and abilities is in itself an important empowering message.

As for the function of myths, the author explains that in the past, the myths were not necessarily false tales. Their main aim was not to relate truthful facts but rather to explain and entertain. This book shared the same aim, with an additional stress on female power.

As the book is written from a gender perspective, the author adds her own evaluation of the characters and events. In the myth of Gaia and Uranus, she notes that Uranus hated the monsters he had begotten with Gaia: “He hated it (the fact that he is the father of monsters) almost as much as he hated the fact that Gaia didn’t actually need him to father anyone.” (Location 98). Here we have an assessment of Uranus’ conduct and feelings. He knows his wife does not need him at all and resents the thought. Gaia, on the other hand, will do anything to save her children, including killing their father. Yet she is presented as a justice-fighter: “Her hunger for justice gave Gaia the strength to devise a plan.” (Location 106). Is Gaia really after justice or revenge? The line between the two is blurred in most cases. Rhea is another mother-figure who resorts to cunning in order to save her children. The mothers, Gaia and Rhea are all-protecting, and they are presented as ideal mothers who will do anything to save their children, whether gods or monsters.

Another example is from the myths regarding Artemis. Artemis is described as a responsible girl, even when she was a baby: “So the first thing the girl did in life was bring forth her twin” (location 271). The author also describes her as having a “keen sense of justice” (as Gaia and Rhea). Are the goddesses just since they must act in a male-dominated society which can be oppressive? The author does not say so, yet the sense of justice is emphasized in some of the stories, although the gods’ justice does not always seem just to modern readers.

Later, after discussing Actaeon and Niobe, the author concludes: “Artemis was strong and caring, loyal and protective: a great daughter, sister, and leader. But you never wanted to mess with her.” (Location 310). After killing Niobe’s seven daughters, this evaluation may seem somewhat of an understatement. Although cruelty of course does not obstruct the fact that Artemis was indeed a great daughter and a leader. Hence this is an example of how one should learn from the goddesses but not imitate them. We should respect our mothers but not act violently on their behalf.

The domineering cruel male figure is more Convincingly shown in the story of Hades’ abduction of Persephone. His complete ignoring of her cries is attested. There is nothing in this story about Hades’ loneliness or his reasoning (not that they can ever justify the abduction) for example as in Julia Green’s Sephy’s Story; rather only his cruel and violent act is emphasized: “Hades grabbed her around the waist and hoisted her onto his chariot, tearing her dress in the process… Tears dotted her cheeks, but that only made him laugh more. He was still laughing as the gash swallowed them both and healed itself.” (Location 391). The tearing of the dress may allude to the rape of Persephone. Her plight and distress are highlighted. Against the suffering mother-daughter duo, stands the male duo of Hades and Zeus. Zeus tells Demeter she should be fair: “Hades – our brother – did not commit a crime. It was an act of love, however misguided” (Location 415). This is the male perception of justice. The above description of Persephone’s abduction does not show any signs of love, caring or tenderness, only violence. When Demeter discovers that Persephone ate the pomegranate seed, she hears Hades’ laugh: “Hades laughed as he had laughed when he plucked Persephone from the meadow and dragged her into gloom” (Location 446). The “plucking” of Persephone, again like a ripe fruit or a flower in full bloom can also have sexual undertones. There is no love in this scene, except that of a mother towards her daughter. In the end, in a message of empowerment, Persephone comes out of this terrible experience stronger than before: “Her time as prisoner had taught her that she was far stronger than she had thought, a goddess capable of much grit and fight” (Location 454). Girls and women may face hardship, yet they should never lose their spirit or stop fighting.

To conclude, this book celebrates goddesses. Although they may be petty, cruel and can even be unjust, this does not lessen the fact that they are powerful and can equally stand up to their male counterparts and achieve great things.

Addenda

The review refers to the Kindle edition.