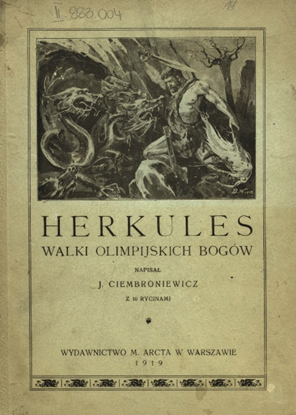

Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Józef Ciembroniewicz, Herkules: walki olimpijskich bogów. Opowieść dla młodzieży. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo M. Arcta, 1919, 61 pp.

ISBN

Available Onllne

Herkules: walki olimpijskich bogów (accessed: December 10, 2021).

Genre

Adaptation of classical texts*

Myths

Target Audience

Children (teenagers, young adults)

Cover

Public domain, available at Polona.pl (accessed: February 5, 2022).

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Adam Ciołek, University of Warsaw, adamciolek@student.uw.edu.pl

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Józef Ciembroniewicz

, 1877 - 1929

(Author)

Journalist, educator and social worker, he was born in 1877 in Wieprz (Wadowice district). In 1897 he worked as a teacher and organized local social life and consumers’ cooperatives. When Poland regained independence after WW1, he worked at the Ministry of Agriculture and was responsible for organizing agricultural schools. He also conducted research into child’s psychology (in cooperation with Aniela Szycówna) and worked on theoretical pedagogy producing many articles on the subject (e.g., Jak wychowywać dzieci w szkole elementarnej, 1918, O zawodowe przygotowanie polskich nauczycieli [An Appeal for Professional Training of Polish Teachers], 1922) and on child psychology (e.g., Kwiaty i dzieci: przyczynek do psychologii dziecka, 1906, Dzieci a ptaki [Children and Birds], 1910; Dzieci a wojna: przyczynek do poznania duszy polskiego dziecka [Children and War. A Contribution to a Better Understanding of the Polish Child’s Soul], 1919). He wrote booklets for children and youth, e.g., Raj ptasi. Nadzwyczajne przygody dwóch chłopców na tajemniczej wyspie, 1910, Mistrz Twardowski [Master Twardowski], 1907; Herkules: walki olimpijskich bogów. Opowieść dla młodzieży [Hercules: Fights Between the Olympian Gods. A Story for Young People], 1919; Pan Lisowski [Mr. Lisowski], 1922, Zdziczały Staszek, 1927 (all links accessed: February 4, 2022).

Source:

"Ciembroniewicz, Józef (1877–1929)", in Władysław Konopczyński, ed., Polski słownik biograficzny, Kraków: Polska Akademia Umiejętności, 1938, vol. 4, 46–47.

Bio prepared by Adam Ciołek, University of Warsaw, adamciolek@student.uw.edu.pl

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

This is an adaptation of Hercules’ myth covering the most important related stories. Among them are Hera’s dislike of Hercules and the story explaining why the Twelve Labours were imposed on the hero. In the first story, Zeus visits Amphitryon’s house in the shape of a wayfarer seeking shelter. Amphitryon hosts him; as a reward for hospitality, the god reveals himself and gives his blessing by anointing Amphitrion’s newborn son, Hercules. Hera, jealous of Zeus’ wasting time visiting a mortal’s house and his blessing of the mortal’s son instead of being with her, becomes Hercules’ enemy. The second story explains the Twelve Labours, not as Hercules’ penance for killing his wife and children in a fit of madness, but as an attempt to seek Hera’s favour. The text includes many dialogues; Ciembroniewicz sometimes uses colloquial phrases and avoids themes he considers inappropriate for young readers (e.g., descriptions of violence; Hercules’ madness and the death of Megara and their children; the fact that Hercules is Zeus’ bastard son). The author mentions (for educational purposes) the scope of power of each god but uses the Polish diminutive of the word “god” (bożek), meaning “a pagan god,” not wanting to offend his readers’ strong monotheistic beliefs.

Analysis

Ciembroniewicz divides and presents the story of Hercules in 20 chapters. Besides the Twelve Labours, the book describes the hero’s infancy, choice at the crossroads, assistance rendered to the Olympians during Gigantomachy, bringing Alcestis back to life, service at Queen Omphale’s court, his marriage to Deianeira, and his death, caused by poison. Hercules is presented here not as a man of flesh and blood but rather as a protagonist of a hagiographic tale – a blameless hero. Prima facie, the author uses ancient sources about Hercules’ life and deeds to construct a framework for the adaptation of the myth. Moreover, the young readers may be familiar with some ancient sources because they were part of the school curricula in the early 20th century and used as simplified texts for translation, e.g., Heracles at the crossroads, a scene known from Xenophon’s Memorabilia. The author changes certain details to meet his double educational goal: learning mythology and providing role models for a moral upbringing.

These changes or omissions of secondary plots considered irrelevant or even harmful for children are evident from the very beginning. As a flawless hero, Hercules cannot be a bastard; his mother cannot be the victim of deception as suggested in Plautus’ Amphitryon. This is the reason for the omission of Iphicles, Hercules’ twin half-brother. In the same chapter, the author mentions famous tutors hired for Hercules, including Linus and Cheiron, but there is no information about poor Linus’ death from the future hero’s hand. Hercules, allegedly perfecting his body, does not neglect his soul and mind (p.10). When the 18-year-old Hercules is sent by his father to attend to his flocks, the author not only claims that the work of a farmer was highly esteemed but also emphasizes the protagonist’s pride in performing such an honourable task (let’s not forget that Ciembroniewicz worked for the Ministry of Agriculture; also Augeas is allegedly passionate about agriculture, p. 30). The scene with Arete (Virtue) and Kakía (Vice) shows that Hercules had no hesitation in choosing Arete. Choosing a suitable path of life is not presented as a difficult moral dilemma, Hercules unequivocally and with contempt rejects Kakia.

The illustration in public domain, source: Polona

Hercules’ choice of Virtue is why in the story of the lion hunt in the Cithaeron mountains, there is no mention of Hercules’ romance with the fifty Thespiades. The modest hero does not admit to the shepherds that Amphitryon sent him but simply slays the lion with one stroke. Hercules’ modesty is also apparent when having defeated the Giants; he asks Hera to assign him any tasks she wants. Hercules’ labours highlight not so much his bravery, strength and intellect but rather his character contrasted with the wicked nature of Eurystheus and Hera. Hercules is a self-made hero, a lonely ranger of the ancient “Wild West,” who protects people from monsters and villains without any human help. His “sidekick’s” character, Iolaus, is also omitted. Divine assistance is barely mentioned. Hercules borrows some helpful objects from the gods, and Athena helps him scare away the Stymphalian birds, but this help does not detract from the hero’s achievements. Removal of the character of Iolaus results in this labour not being scored (instead of the second labour).

In Ciembroniewicz’s adaptation of the myth, Hercules slays monsters, but there are no other casualties. The only “victims” are wild lions, a hydra, a few Stymphalids and Poseidon’s water dragon of Troy; as these monsters threatened local communities, their killings were considered good deeds. As for the human dead: perfidious Augeas and Laomedon die in a fray; Diomedes is devoured by his horses – all deaths result from hubris or the breaking of agreements, seen as contempt of the gods. The author gives the hero a moral right to eliminate them. He spares, however, some others who Heracles traditionally killed: Centaurs at Pholos’ who attacked Hercules when he was a guest. They are shot with arrows but do not die as they retreat and hide in their caves. The Amazons and Geryon’s army are vanquished and wounded, but nobody dies, even Nessus is only wounded with an arrow. The Ceryneian hind’s injury is immediately healed with care by the hero himself who wisely uses the herbal remedies he learned from Cheiron – which shows that Hercules is strong and brave but, in general, kind, gentle and reasonable – according to the maxim: “with great power comes great responsibility.” Hercules acts against a human only in case of contempt of the gods’ laws. The only exception is Iphitus, whom Hercules kills in self-defence. Hera stabs the sleeping Hercules with a dagger to make him believe that Iphitus attacked him. The resulting death deeply affected the protagonist, who let himself be enslaved and humiliated at Omphale’s court without protest. Because the secondary plot featuring his marriage to Megara is omitted, the madness, which cost him the lives of his family, is gone too. Hercules is flawless, a good and faithful husband to Deianeira and, again, his death is caused by Hera’s intrigue and not by his affair with Iole.

Although Hera is described in the ancient sources as a goddess unfriendly to Hercules, here, she is presented as an active foe, a hostile deity who intrigues against him with the intend to murder. Hera’s husband’s adultery, as the reason for her wrath, is not mentioned, although she is shown to chase and persecute the hero, envious of her husband's attentions shown towards Amphitryon, an ordinary mortal. She is a villain misusing her power to harm Hercules in every possible way.

Unfortunately, there are some minor inaccuracies: Hercules releases arrows dipped in the blood of the chimaera (mistakenly spelt himera), and not hydra (p. 26); it is Acheloos who allegedly convinces “Nessus and centaur” to kidnap Deianeira (p. 59); Diomedes lives in… France, (p. 36). Some of these inaccuracies may result from typing errors, like calling Minos – Ulinos (possibly, an incorrect deciphering of the manuscript (p. 33ff.); we find the exact wrong spelling of the letter “M” in Mycenae (p. 34)“Ul” instead of the initial M.

Further Reading

Apollodorus, The Library, vol 1, vol 2, trans. James Fraser, London: William Heinemann; New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1921 (accessed: January 18, 2022).

"Ciembroniewicz, Józef", in Władysław Konopczyński, ed., Polski słownik biograficzny, Kraków: Polska Akademia Umiejętności, 1938, vol. 4, 46–47.

Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, trans. C. H. Oldfather, vol. 3, The Loeb Classical Library 340, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, London: St Edmundsbury Press Ltd., 1939 (accessed: January 18, 2022).

Euripides, “Heracles” in The Complete Greek Drama, edited by Whitney J. Oates and Eugene O'Neill, Jr. in two volumes. 1. Heracles, translated by E. P. Coleridge, New York. Random House. 1938 (accessed: January 18, 2022).

Kulus, Magdalena, „Arctowie dzieciom”, Bibliotheca Nostra. Śląski kwartalnik naukowy 3 (2011): 71–78 (accessed: January 18, 2022).

Addenda

Editio princeps includes 10 black-and-white illustrations by “B. W. 1912”.