Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Filippos Mandilaras, Το χρυσόμαλλο δέρας [To chrysómallo déras], Greek Mythology [Ελληνική Μυθολογία (Ellīnikī́ Mythología)]. Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2012, 16 pp.

ISBN

Official Website

www.epbooks.gr (accessed: September 04, 2017)

Genre

Illustrated works

Target Audience

Children (aged 4+)

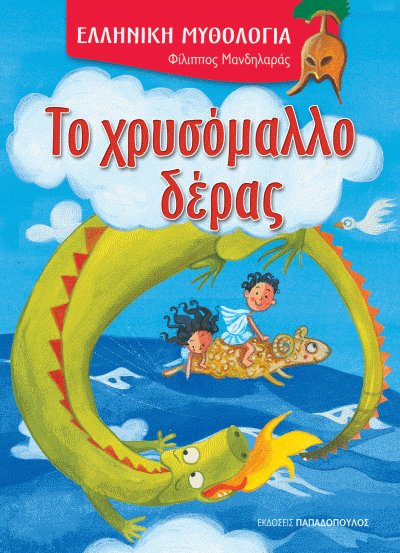

Cover

Courtesy of the Publisher. Retrieved from epbooks.gr (accessed: July 5, 2022).

Author of the Entry:

Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

Natalia Kapatsoulia (Illustrator)

Natalia Kapatsoulia studied French Literature in Athens, and she worked as a language tutor before embarking on a career as a full-time illustrator of children’s books. Kapatsoulia has authored one picture book Η Μαμά πετάει [Mom Wants to Fly], which has been translated into Spanish Mamá quiere volar. Kapatsoulia, who now lives on the island of Kefalonia, Greece, has collaborated with Filippos Mandilaras on multiple book projects.

Sources:

Official website (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Profile at the epbooks.gr (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Filippos Mandilaras

, b. 1965

(Author)

Filippos Mandilaras is a prolific and well-known writer of children’s illustrated books and of young adults’ novels. Mandilaras studied French Literature in Sorbonne, Paris. His latest novel, which was published in May 2016, is entitled Υπέροχος Κόσμος [Wonderful World], and it recounts the story of teenage life in a deprived Athenian district. With his illustrated books, Mandilaras aims to encourage parents and teachers to improvise by adding words when reading stories to children. Mandilaras is interested in the anthropology of extraordinary creatures and his forthcoming work is about Modern Greek Mythologies.

Sources:

In Greek:

Profile on EP Books' website (accessed: June 27, 2018).

i-read.i-teen.gr (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Public Blog, published 15 September 2015 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Press Publica, published 28 January 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Linkedin.com, published published 6 May 2016 (accessed: February 6, 2019).

In English:

Amazon.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

On Mandoulides' website, published 7 March 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

In German:

literaturfestival.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Adaptations

The book is an adaptation of the book published in 2008 within the series My First Mythology:

Filippos Mandilaras, Το χρυσόμαλλο δέρας [To chrysómallo déras]. Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2008, 36 pp.

Demo of 9 pages available at epbooks.gr (accessed: October 13, 2021).

Summary

King Athamas, prompted by his second wife Ino, intends to sacrifice his son, Phrixus, but a golden ram appears and carries Phrixus away. Phrixus and his sister, Helle, ride the flying ram across the seas. Helle falls to her death over a narrow sea passage. At Colchis, Phrixus sacrifices the ram to Zeus and offers its golden fleece to king Aeetes. A dragon guards the fleece.

Many years later, Jason requests the golden fleece from Aeetes. To receive it Jason is tasked with ploughing the land with two wild bulls, sowing with a dragon’s teeth, and killing all who spring up. With Medea’s magic potions, Jason accomplishes what Aeetes set for him. Aeetes, nonetheless, does not keep his word. So, Jason steals away the golden fleece, with Medea’s and Orpheus’ help. The Argonauts and Medea sail away from Colchis, but Aeetes and his men pursue them. When Aeetes’ boats get close, Medea throws her young brother Apsyrtus in the sea. Aeetes stops the pursuit to collect his son’s body. Zeus becomes angry with this terrible killing. As a result, the Argonauts’ return journey to Iolcus lasts for many months. They pass the Sirens’ island and Crete, where the bronze giant Talos throws rocks at them. Following Apollo’s mediation, Zeus’ anger subsides and the Argonauts find themselves at Iolcus. There, Pelias does not give up his throne. Jason and Medea flee to Corinth, and they have children. One day, however, Jason forgets his oath to be with Medea for ever and falls in love with another woman. In revenge, Medea kills Jason’s two children. Jason is inconsolable and remembers Argo and the glorious past.

Analysis

This book can be read together with the book about Jason and the Argonauts, ‘Ο Ιάσονας και η Αργοναυτική Εκστρατεία’, which is discussed elsewhere in this database. The story here is more complex, with multiple travels and reversals of fortune. From Orchomenus in Boeotia Phrixus and Helle fly to Colchis via the Hellespont. After leaving Colchis, the Argonauts wander around, perhaps like Odysseus and his comrades, and even find themselves in Crete, that is, in the southern Aegean and far away from Iolcus, their destination in Thessaly. On reaching Iolcus, Jason and Medea have to run away again, to Corinth. The golden fleece seems to be causing an incessant movement of people, and travel by air, sea, and land.

Mandilaras’ text commences with a journey back in time (Θα πάμε πίσω στα χρόνια τα παλιά in Greek), as if the adult reader were to recount a folk or fairy tale. Yet, the narrative deals with some difficult topics. Readers are confronted with the death of several children, first Helle, then Apsyrtus, and finally Jason’s children. The first death is accidental, but the others are murders by one and the same person, Medea.

There are both benign and horrific aspects to Medea’s witchcraft, and personality more generally. Medea is described from the start as a witch (μάγισσα in Greek), rather than a princess even though she is a king’s daughter. Any likeness to a fairy-tale princess is diluted. She is portrayed as an alluring and possessive figure, who loves Jason and expects fidelity from him. Her magic tricks are instrumental in Jason’s success. When Jason enters the forest to steal the fleece, we read that Medea touches the dragon with a magic potion. Kapatsoulia’s illustration shows Medea as a young and smiley brown-haired female in a simple red robe, without any jewellery and excesses that readers may have expected from a princess. Her unassuming attire may contrast with the glitter of the golden fleece, which, as we read, hangs from an oak tree ‘to illuminate the forest’ (το δάσος να φωτίζει in Greek). This depiction of Medea contrasts with golden finds that have been recovered archaeologically from the lands of Colchis.*

Medea holds a globular glass bottle and sprinkles the potion with a feather. The image might remind readers of an ink bottle and a quill pen. Medea’s magic powers appear to be gentle, and yet effective. The dragon has happily fallen asleep, clutching a pillow and unaware that Medea rests on its body. Medea’s magic touch has a calming effect that tames the beast. At this instance, Medea is not to be seen as evil, which is appropriate for children as young as four.

By contrast, Medea’s vicious nature emerges gradually in subsequent episodes, which are surely not palatable by four year-olds. When the Argonauts struggle in heavy seas because of Zeus’ anger, Medea’s gaze is frightening for the crew. More crucially, when Jason loves another woman at Corinth, we read that ‘Medea becomes again a witch from the East’ (Η Μήδεια γίνεται ξανά μάγισσα απ’ την Ανατολή in Greek) and slaughters Jason’s two children. Here, the East implies the lands of Colchis on the eastern shore of the Black Sea, present-day Georgia. This far-away destination is somehow envisaged as a place of magic, and possibly even of Medea’s cruel character. No mention is made that Thessaly, too, where Jason set off from, was also considered a place of witchcraft in ancient literature.**

Medea exhibits no compassion after the murder, and she leaves Jason all alone. The illustration on the last page shows Jason, and not the killing. Jason’s poor psychological state could be yet another difficult issue for young children to come to terms with. The events here are more attuned to an adult readership familiar with Euripides’ Medea and its plethoric cinematic adaptations. The latter include director Jules Dessin’s 1978 film A Dream of Passion (Κραυγή Γυναικών in Greek), starring legendary Greek actress Melina Mercouri, which problematizes a betrayed woman’s psychology.***

On the whole, it may not be the quintessential ancient witch Medea that aligns Classical myth with magical stories in modern children’s literature. There are more elements in the text and image that have magical connotations and can resonate with contemporary popular culture. A ram that is golden and can fly, carrying two siblings, seems to have extraordinary (magical) powers. The dragon, moreover, is a favoured (magical) creature in children’s folktales. As a consequence, Jason’s feats may be seen also as magical adventures, since they include, for example, the sowing with a dragon’s teeth. The overall magical ambience may soften the cruelty of the killings and/or direct young children’s attention away from these incidents in the story.

* See, for example, the golden jewellery from the cemetery at Pichvnari: Tsetskhladze 2018, 468, fig. 15. Gocha R. Tsetskhladze, ‘The Colchian Black Sea Coast: Recent Discoveries and Studies’ in Manolis Manoledakis, Gocha R. Tsetskhladze and Ioannis Xydopoulos, eds., Essays on the Archaeology and Ancient History of the Black Sea Littoral, Print. Colloquia Antiqua (Ser.); 18, 2018, 425–545.

Available from: www.peeters-leuven.be (accessed: 02 August, 2019).

** See, for example, Oliver Phillips, ‘The Witches’ Thessaly, in Paul Allan Mirecki and Marvin Meyer, eds., Magic and Ritual in the Ancient World, Leiden: Brill. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World, v. 141, 2002, 378–386.

doi.org (accessed: 02 August, 2019).

*** See Nugent, S. Georgia, “Euripides' Medea: The Stranger in the House”, Comparative Drama 27. 3 (1993): 306–327.

Addenda

Published in Greek. Soft bound.