Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

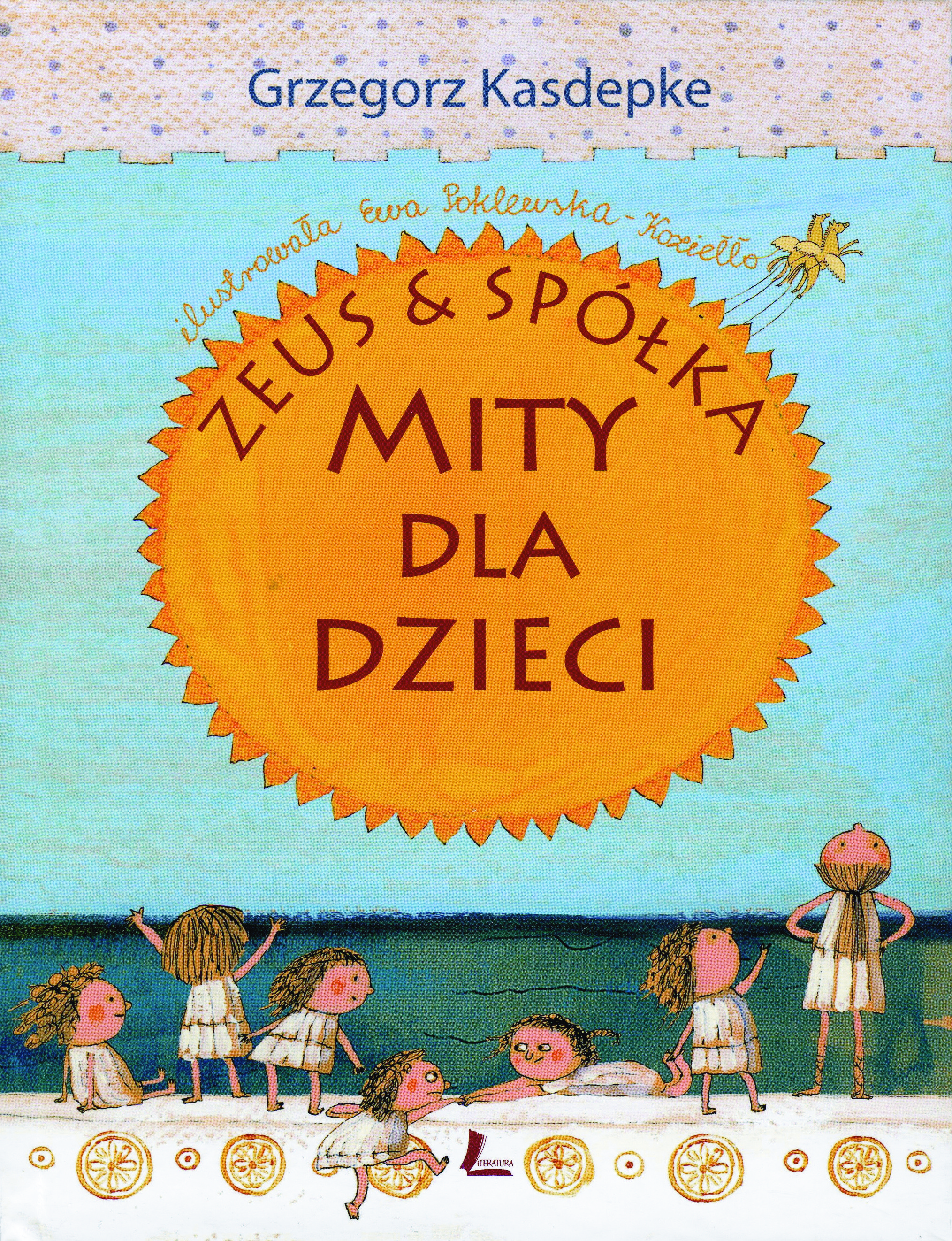

Grzegorz Kasdepke, ill. Ewa Poklewska-Koziełło, Mity dla dzieci – Zeus & spółka. Łódź: Wydawnictwo Literatura, 2011, 96 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Anthology of myths*

Target Audience

Children

Cover

Cover design and illustrations by Ewa Poklewska–Koziełło. Łódź: Wydawnictwo Literatura, 2011. Courtesy of the publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Marta Adamska, University of Warsaw, m.adamska91@student.uw.edu.pl

Summary: Dorota Rejter, University of Warsaw, dorota@bazylczyk.com

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Photograph by Katarzyna Marcinkiewicz, courtesy of the Author.

Grzegorz Kasdepke

, b. 1972

(Author)

Born in Białystok, now lives in Warsaw. Attended Faculty of Journalism and Political Science at the University of Warsaw. He made his journalistic debut in the weekly “Polityka.” Author of books for children and teenagers, among them many bestsellers. From 1995 to 2000: Editor-in-Chief of the popular magazine for children “Świerszczyk” [The Little Cricket]. Wrote a number of radio-plays for children, as well as scripts for TV programs and series (Ciuchcia [The Choo-Choo Train], Budzik [The Alarm Clock], Podwieczorek u Mini i Maxa [Afternoon Tea at Mini and Max]). Awarded a number of literary prizes. In his books, Kasdepke attempts to explain to his young readers the complicated adult world demonstrating a sense of humour and an understanding of their needs, like for example in books and audiobooks: Co to znaczy... 101 zabawnych historyjek, które pozwolą zrozumieć znaczenie niektórych powiedzeń [What Does It Mean... 101 Funny Stories Helping to Understand the Meaning of Some Expressions], 2002; Bon czy ton. Savoir–vivre dla dzieci [Bon or Ton. Savoir–vivre for Children], 2004; Horror! Skąd się biorą dzieci [Horror! Where Do the Children Come from?], 2009; Kocha, lubi, szanuje, czyli jeszcze o uczuciach [Loves, Likes, Respects, or Again about Feelings], 2012; W moim brzuchu mieszka jakieś zwierzątko [A Little Animal Lives in My Tummy], 2012. He is also the author of crime stories for children – a series of books about Detektyw Pozytywka [Musical Box Detective], 2005–2011. Received the Kornel Makuszyński Prize for his book Kacperiada. Opowiadania dla łobuzów i nie tylko [Kacperiada. Stories for Rogues and not Only], 2001, inspired by his son Kacper. He considers himself “a 100 per cent fairytale writer.” In a recent TV interview the author confirmed the preparation of a new book for children inspired by ancient mythology – Banda trupków i sandały Hermesa [A Gang of Corpsies and Hermes’ Sandals]. Kasdepke wrote about twenty short stories – adaptations of myths, published in five volumes with varying contents, see descriptions below (with a particular stress on the presentation of the most recent volumes). In 2019 he was awarded the Order of the Smile, an international award given by children since 1968.

Bio prepared by Dorota Rejter, University of Warsaw, dorota@bazylczyk.com, and Maria Karpińska, University of Warsaw, mariakarpinska@student.uw.edu.pl

Translation

Czech: Řecké mýty pro děti, trans. Marta Harasimowicz, Praha: Slovart, 2017.

Russian: Mify dlâ detej, trans. Anna Burmistrova, Minsk: Popurri, 2019.

Slovak: Grécke mýty pre deti, trans. Jozef Marušiak, Bratislava: Buvik, 2015.

Ukrainian: Mìfi dlâ dìtej, trans. Božena Antonâk, L'vìv: Urbìno, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019.

The translated editions combine Mity dla dzieci – Zeus & spółka with Mity dla dzieci in one collection of 20 myths.

Sequels, Prequels and Spin-offs

Grzegorz Kasdepke, Mity dla dzieci. Łódź: Wydawnictwo Literatura, 2009.

Summary

The magical and amazing world of ancient gods and heroes shown in an accessible way in amusing and straightforward language. Each story focuses on a different god or hero.

This is a collection of well-known myths adapted for children and told in a simple, funny and clear way. The stories are very interesting and present the most important mythological characters. The book includes original illustrations.

The selection includes the myth of the origin of the world, Cronus’ golden age and the Olympians, the myth of Prometheus, Pandora’s box, Aphrodite, Hermes’ tricks, Persephone’s abduction, Daedalus and Icarus, Europa’s abduction and the foundation myth of Thebes, Midas’ donkey ears and his golden touch, and Theseus’ myth.

Analysis

After Myths for Children's success, the author adapted ten more myths for young children written in the same light and humorous convention and illustrated by the same artist. His approach used in the previous volume has been maintained. The stories set in mythical antiquity are brought close to the child reader through the following devices: a simple vocabulary adjusted to the reader’s age (including the use of diminutives), witty dialogues written in the convention of modern everyday speech instead of serious and pompous discourse, comparisons to familiar things or situations, and accessible explanations of difficult terms or adult issues. Additionally, colorful illustrations of Ewa Poklewska-Koziełło make the mythical characters less distant and allow children to relate to them, learn Greek myths effortlessly, and absorb cleverly disguised moral lessons provided in an exciting, light manner.

In the first myth – about the beginnings of the world – Kasdepke compares the logistics involved in the ordering of the world to any other complex activity: elevated stress and a nervous atmosphere is a normal consequence of people (or Greek gods) arguing and quarrelling; their marriages can fall apart, especially since they have troublesome children (here represented by the Hecatoncheires triplets). In such circumstances, Uranus becomes weaker, and Cronus can easily hurt (no mention how) him and defeat him. Then the new ruler begins to reign in a just and wise manner, "but power takes away sanity even from gods" (p. 8), which explains to the reader Cronus’ later incomprehensible and cruel behaviour. Baby Zeus is presented as a perfectly ordinary, contemporary child – as an infant, he needs to be changed; every evening, he fusses before going to bed, and he loves eating sweets and has his favourite pet, a likeable goat. All these elements produce an image of a normal child. His cruel baby-swallowing father is punished, first of all by the humiliation – easily grasped by a child – of vomiting before he reaches the toilet and then, more permanently, by his defeat concluding a decade of war.

In the myth of Prometheus, the reader gets a moral lesson about the consequences of theft. Although Prometheus is presented as an undeniable benefactor of humanity and his act of stealing is caused by good intentions and willingness to help, he does not avoid a cruel punishment; he understands that theft, even to help others, must be punished. Similarly, the myth of Pandora brings a moral lesson about jealousy. This emotion is described as "nothing cool. If you have ever been jealous, you know well what a nasty feeling it is. A jealous man is constantly angry, grim, cannot focus on anything, nothing brings him joy. What is worse, the jealousy can push anyone to do something wrong." (p. 23). The real protagonist of this myth is Zeus, who is jealous of Prometheus’ popularity. Pandora is only a means to achieve the gods’ goal, stereotypically beautiful but not perfect. Having tricked humans, gods laugh and do not even realize, or care, how much evil they just caused. Importantly, the myth has a comforting ending in which hope is released from the jar, contrary to other versions of the story, where hope is not released. The evidence is overwhelming: when we are sad, we hope for a better tomorrow.

Hermes' myth presents a troublesome child whose jokes are unacceptable, but he is still accepted and liked by the others. During his banishment from Olympus, the place seems too quiet and serious. Finally, his qualities are being used for honourable purposes, humans, among whom he was exiled, gain a mighty friend and protector. The myth can encourage hyperactive children to have higher self-esteem, recognize that they are loved, liked, and matter to others, despite their disruptive behaviour.

The following myths focus on obedience to one’s parents. The child reader can realize that parents establish rules based on love and care with the intention to warn and protect children. In the myth of Persephone, Demeter acts exactly like a working mother who has to leave her child home alone – before leaving, she gives her daughter some boundaries, but the girl breaks them, and in consequence, she is kidnapped. Similarly, Icarus nods to his father but does not listen or follow his advice, which eventually leads to his death. The third disobedient character is Europa. Her example also illustrates another important warning: "it is better not to approach unknown animals, even if they look the most gentle" (p. 65). Such a lesson can be particularly useful in realising that any animal, especially an unknown one, can be potentially dangerous, bite, scratch or kick, and be carefully avoided unless its owner is present and can control it.

King Midas's myth teaches that we must not be greedy and always be careful what we wish for. The myth of Theseus presents a boy who dreams of being like his favourite superhero, Hercules, instead of Superman or 007. With Hercules’ example in mind ("Hercules was afraid as well… (…) but he defeated worse monsters"… (p. 94)), Theseus overcomes his fear. Finally, he becomes a real hero himself, not by slaying the Minotaur, but by defeating fear itself. The book ends with Ariadne telling him that now, young boys will dream of being like Theseus.

Further Reading

Hajduk-Gawron, Wioletta, "Sfera linguakultury jako niezbędny element integracji”, Postscriptum Polonistyczne 2 (2019): 247–258 (accessed: May 7, 2021).

Niesporek-Szamburska, Bernadeta, “Dobre maniery, czyli o dydaktyzmie we współczesnej literaturze dziecięcej” in Bernadeta Niesporek-Szamburska and Małgorzata Wójcik-Dudek, eds. Nowe opisanie świata: literatura i sztuka dla dzieci i młodzieży w kręgach oddziaływań, Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego, 2013, 55–69 (accessed: May 7, 2021).

Plieth-Kalinowska, Izabela, „Świadomość językowa uczniów klas trzecich szkoły podstawowej”, Przegląd Pedagogiczny 1 (2015): 111–118 (accessed: May 7, 2021).